On much of the African continent, 15 years ago there was an almost total absence of landline telephone technology. Now, with smallholder farmers as much at the forefront as any of their urban small business counterparts, the landline situation remains the same, but the bandwidth of Africa is abuzz with smartphone communications that have transformed the way the continent does business.

Why it matters: If such a transformation can occur so quickly and so completely in telecommunications, argued one of the guests at the recent Arrell Food Summit hosted by the University of Guelph, why couldn’t a similar and similarly rapid transformation take place in the way the continent produces food and feeds its people?

Sam Thevasagayam, Sri Lankan-born Deputy Director of Agriculture Development for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, was joined by Oxford University global food security specialist Sir Charles Godfray in bringing a decidedly developing-world focus to the third and final day of this year’s inaugural Arrell Food Summit.

“In Africa, they went from nothing to mobile phones everywhere,” Thevasagayam said, when asked near the end of his session what innovations the high-profile philanthropic foundation supports. “So it should be possible to bring innovation in agriculture to those same regions.”

As an example, he suggested 25 per cent of potential production in livestock in Africa is lost to preventable diseases. The Foundation calculated the potential growth in demand in Africa for animal-based proteins in the diet as the continent’s population gains more economic power, and called on the CEOs of the world’s top-eight animal health product manufacturers to assess if it would be economically feasible to begin offering their products to African smallholders in an affordable way.

The CEOs responded they recognized the potential, but that it would be impractical for them to get into business in Africa because there is an almost complete lack of regulation for the industry. The Foundation then went to African government leaders and told them what the CEOs believed, and the government leaders suggested it would be pointless for regulations to be set up if no companies were willing to come into the continent. A chicken-and-egg argument.

Read Also

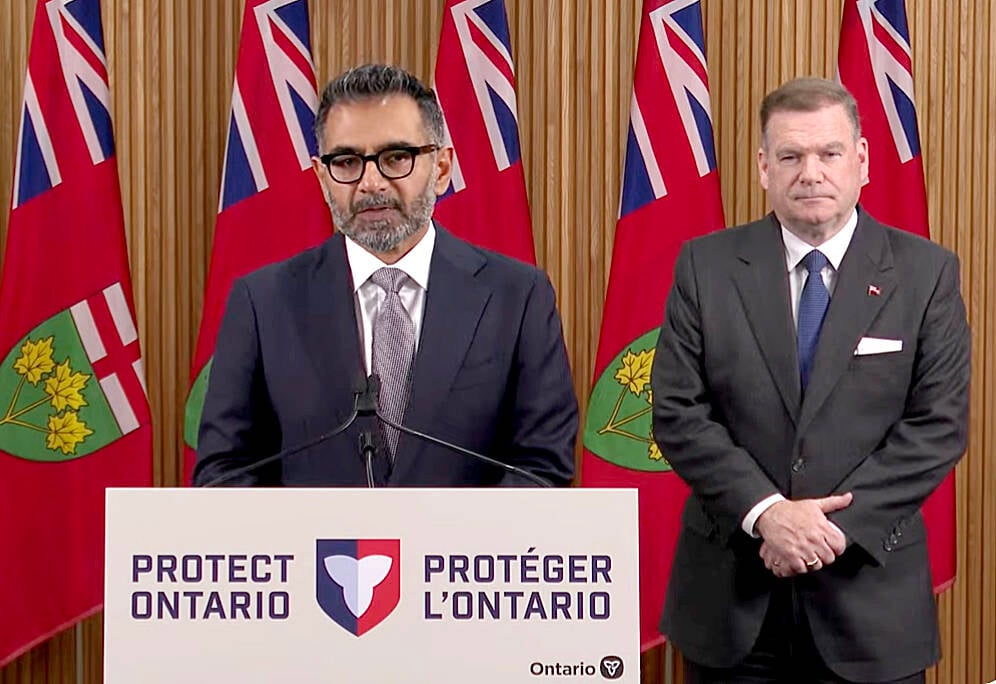

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

The Foundation’s innovation, Thevasagayam reported, was bringing the two sides together for talks. Now, over the past 18 months, four out of the top eight companies have started doing business in Africa. “I’m really excited about that.”

Godfray, director of the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food, likewise put considerable focus on Africa. He identified population growth in the developing world as a key issue but cautioned Food Summit attendees that we, as the rich world, should be very careful about projecting our ideas on those in the developing world. The true issue isn’t population growth per se, but rather over-consumption of the world’s ecological resources, he stressed. “And we, in the rich world, consume far, far, more.”

We must also keep in mind, he continued, that an overall goal is to allow people currently at risk of hunger to rise to the status where they can safely and sustainably consume more, and more nutritious, food.

Asked by U of G moderator, Applied Nutrition Professor Jess Haines, what would be the keys to feeding the world in the year 2100, Godfray replied, “we would be eating less meat, and we would have allowed the demographic transition (to a predicted levelling-off of growth late this century) to go through in the developing world . . . And, hopefully, we will have gotten our act together on climate change.”

Addressing the Summit’s theme, Godfray identified an innovation very familiar to Ontario’s farmers: precision agriculture. He qualified, however, that he doesn’t necessarily think of it in the same way.

“If there were Klingons about, it would be like an episode of Star Trek,” the Oxford University specialist commented, after describing to the Food Summit guests – many of whom represented city-based organizations such as food banks and food policy thinktanks – what “precision agriculture” means in the fields surrounding the Summit’s southern Ontario host cities.

But the concept can also be transferred into “low-tech, high-labour precision agriculture,” he stressed, if you think about an African smallholder farmer with a smartphone instructed to apply small packets of crop inputs to a portion of his field in keeping with the data that has been collected, thereby increasing yield and profit.

Speaking to Farmtario several days after the inaugural Food Summit, Arrell Food Institute Director Dr. Evan Fraser expressed gratitude for the willingness of Godfray, Thevasagayam, and fellow Thursday guests Galen Weston and Sheila Watt-Cloutier to share their perspectives.

“When we set out to host this Summit, we wanted to have a fulsome, informed discussion about how we might sustainably, equitably, nutritiously feed the future human population of the Earth, and I certainly think we accomplished that in a stronger way than I could have imagined,” he said.

Also as part of Thursday’s proceedings, an evening gala at the Four Seasons Hotel saw the official presentation of two inaugural Global Food Innovation Awards, for which Godray, Thevasagayam and Watt-Cloutier had served as adjudicators. Winners of the $100,000 prizes, chosen for making a difference in global food security in the areas of community engagement and scientific research, were the worldwide Solidaridad Network for its invention and continued support of the fair-trade concept, and Harvard University’s Dr. Samuel Myers, for his studies into the intersection of climate change and agriculture.

Fraser said it has not yet been decided whether the Arrell Food Summit will become an annual event. He could only say that hosting a meeting of the Summit’s stature was one of the elements identified when the Food Institute was created at the U of G in 2017 through a donation from the Arrell family.