The shock and awe of drones may be less than it was a decade ago, but the agricultural potential of the technology continues to develop.

Artificial Intelligence (AI), and a better understanding of scalability give drones and drone operators the ability to gather and usefully interpret field information down to the millimetre level.

Why it matters: Drones can provide detailed field information and its capabilities continue to increase. However, they are not a complete replacement for other technologies or agronomic practices.

Read Also

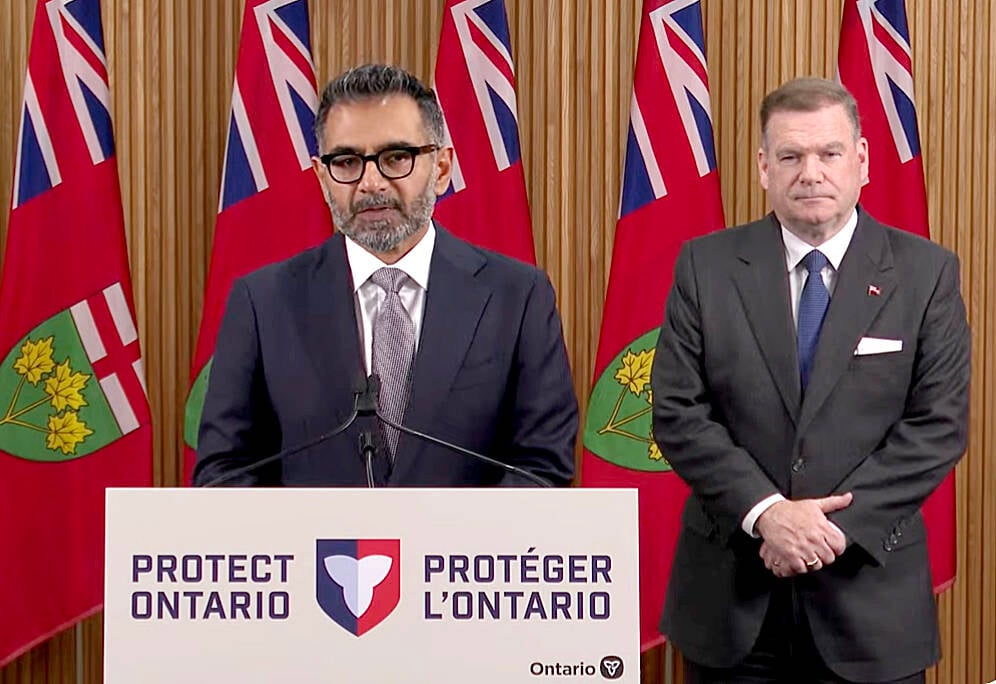

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

Data has to be useful

According to Norm Lamothe, a Peterborough-area grain farmer and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operator, building and layering data has been a key approach to improving the usefulness and profitability of drone tech.

Lamothe, who is also co-founder of Deveron UAS, a drone and data company operating in Canada and the United States, says Silicon Valley promoters and data companies initially promised many things that drones could not achieve, at least given where the technology was five years ago.

Like other data-driven technologies, drones were creating plenty of field images and static data that farmers could not use.

“(Drone tech promoters) didn’t have a lot of know how about grower challenges,” says Lamothe. “You really have to listen to growers and what they can do at the field level …. Growers don’t have room to take risks.”

Practical improvements improves profitability potential

A better understanding of building and layering data has been critical to improving the usefulness and profitability of drone tech.

For Lamothe, this coincides with going after “low-hanging fruit,” such as services focused on variable rate scripting, imagery for variable rate nitrogen and fungicide applications, and those combining mid-season drone flights (to analyze visible crop health) with soil sampling to highlight potential nutrient deficiencies.

“What I see on my farm and the decisions we made, there’s opportunity to extract another $200 to $300 per acre,” Lamothe says. “We don’t farm a lot of acres so we have to farm really well. It’s farming to the acre now as opposed to farming the field.”

Mike Wilson, program lead with Veritas Farm Management, an agricultural service company based in Chatham, and a subsidiary of Deveron UAS, says his company has had success with using drones to address plant population variability.

Wilson says they fly small drones rather than larger fixed-wing aircraft, eight metres off the ground very early in the growing season (shortly after emergence). The drone photographs key checkpoints, which themselves are identified on zone maps created by combing elevation and historical yield data with soil sampling information, as well as seeding rate variability. Stand gaps are highlighted, and the client can then replant those areas either manually or using variable-rate equipment.

An entire field can be accurately covered in minutes, which Wilson says makes it more time efficient and more thorough than physically walking the field. The same stand information could also be used to make crop insurance claims.

Wilson and his colleagues, in partnership with Grain Farmers of Ontario, are also researching how drones can be used to predict nutrient availability in the next growing season. More specifically, they are looking at how biomass and crop colour (leaf data) in red clover can indicate nitrogen availability for crops planted the following spring.

Lamothe adds the ability of drones to generate detailed and consistent data sets also makes them an important tool in the general research sense.

Machine learning the next hurdle

Lamothe says the next step in drone tech involves AI, or developing intelligent machines that can make independent, clearly communicable in-field decisions. Steve Laevens, UAV operator and sampling coordinator with Veritas, says this technology is already being used by his company in its stand-count service.

“We fly the drone and tell it ‘that’s a corn plant.’ It keeps going, sees something else green, and asks ‘is this a corn plant?’ We say no. It keeps going and asks (again) and we say yes. Do that enough times and it learns,” says Laevens. “That becomes machine learning as the data grows.”

He says the same principal also applies to other agronomic measurements, from identifying manganese deficiency and weed pressure to finding rocks, trash, or other obstructions that could damage equipment.

Limitations

Advancements have been made in incorporating machine learning with drone technology, but Lamothe says limitations still exist when it comes to scalability. Satellite imagery, for example, is a complimentary tool that can provide cheaper options for covering large acreages. Satellite data, however, is not as detailed.

Wilson expresses a similar sentiment. The accuracy and reliability of satellites has come a long way, he says, and they provide good information at the metre level. However, drones can operate on a millimetre scale and don’t have to worry about barriers like cloud cover.

“Drones will always do things satellites don’t. They are on different platforms,” he says. “Satellites are just as important. They are probably the more scalable.”

Drone tech; then and now

“There have been significant improvements in drone technology even within the last year; comparing it to five years ago would make those models look ancient,” says Johann Reandino, director of business development for OmniView Tech, a Canadian drone sales company.

Reandino says notable improvements include added safety features such as collision avoidance sensors, improved connectivity, and better programming intelligence. He adds future models will include the capability for drones and manned aircraft to alert one another when flying nearby.

While drones have potential uses in many industries, Reandino says the agriculture drone sector has been booming due to their usefulness in gathering plant data.

As for limitations, he says highly inclement weather is still a barrier for day-to-day drone operation. Some units are waterproof, he adds, though it is generally unadvisable to fly in severe weather anyway. Incorporating better weatherproofing, as well as improving battery life and range, is also being worked on.

“It all depends on manufacturing costs, but costs are indeed getting lower to provide greater accessibility,” says Reandino.