Large corporations are continually investing in new food and agriculture technologies — but not just with the intent of gaining quick financial returns.

According to corporate investment managers, start-ups in the agri-food sector need to understand the strategies of potential investors if they want to attract investment capital.

Why it matters: Investor interest in agriculture innovation is high, but agriculture start-up companies often get one shot at impressing investors. Here are some tips from the investors.

Representatives of agri-food giants Cargill, Tyson Foods Inc., and BASF told a panel discussion at the AGRI-Tech Venture forum in Toronto on May 10 that establishing both long and short-term goals with prospective start-ups, as well as establishing clear lines of communication, are critical to any green business relationship.

Read Also

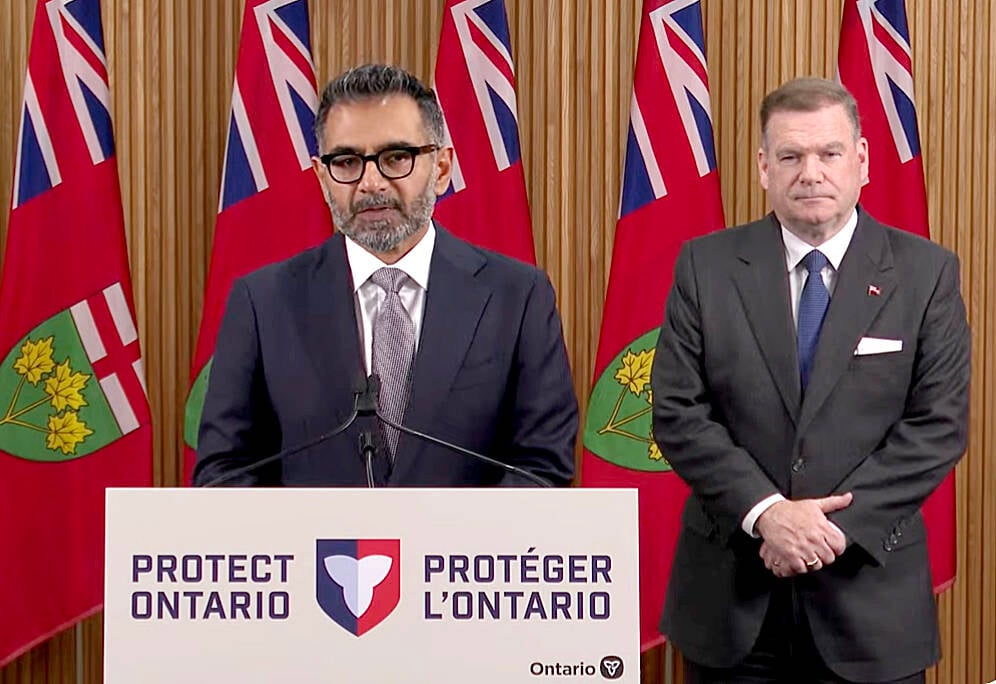

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

According to Reese Schroeder, managing director of Tyson Ventures — the investment division of Tyson Inc. — prospective investment recipients should know what the targeted company expects for returns, market longevity, or environmental sustainability. It’s also critical to incorporate those characteristics into the investment pitch.

“We’re looking for good teams of people. We don’t just go to the CEO and say we are ready to invest,” said Schroeder. “We’ll go out and meet with the team, see where they’re working, get a feel for their culture and the environment of a company. A great team with really good technology will beat a poor team with excellent technology every time.”

Bill Aimutis, global innovation director for Cargill, agreed adding that inadvertently slamming business areas in which the investor deals — say, when espousing the supposed environmental merits of plant-based burgers to a primarily animal-protein company — is not helpful from a business standpoint. Such cases, though, are not unheard of.

Establishing clear lines of communication does more than just reassure the investor. Jacob Grose, investment manager for BASF’s venture capital division, said start-ups should also know what non-financial benefits an investor might offer in addition to capital.

“What can (an investor) bring to the table that you might not find elsewhere? We could be a large customer, potentially, maybe a channel to a specific market,” said Grose.

“In BASF’s case, our customers are the farmers. We sell to farmers, have a huge global sales force that’s talking to farmers every day… along with product registration and other things, I think we can help knock-down those barriers.”

Grose said having a large multi-national on one’s list of investors is never a bad thing from a business-growth perspective. Indeed, it helps other companies take the start-up more seriously.

Despite some differences in the overall business goals of their companies, Schroeder, Aimutis, and Grose stressed the importance of finding mentors — including those that don’t invest capital — to help disentangle the business environment. That means finding both a solid mentor business, as well as an entrepreneur that, as Aimutis said, “has been there and done that so you know what’s going to bite you in the backside later, and get forward.”

Mentors can help start-ups navigate the regulatory systems of different countries. The process of getting a product to European Union markets is very different than doing so in China, for example.

Mentors can also assist in the development as well as in the development of company governance. This could include the implementation of board principles and procedures, or training for those making decisions.

“We’re in a strange position right now in agriculture and food,” said Aimutis. “Over the next 20 to 30 years, regulatory requirements, especially as we get back to points that we are still losing land, still damaging the water, still damaging the air, are going to be changing very rapidly.”

“Startups are going to have a really hard time following that.”