A street scene photographed back in Britain’s horse-and-buggy days is symbolic of how the world has traditionally looked upon Canada as a food exporter.

“Canada: Britain’s granary” is boldly splayed across a decorative archway on a busy avenue.

And it was a granary of sorts, just as it is today.

As much as Canadians see themselves as global traders, to this day our reliance on exporting agricultural commodities is largely a function of our colonial past.

From the time this part of the world was “discovered,” it’s been where the rest of the world has come shopping for ingredients, from furs to wheat to canola, to support their cultural creations, be they for fashion or food.

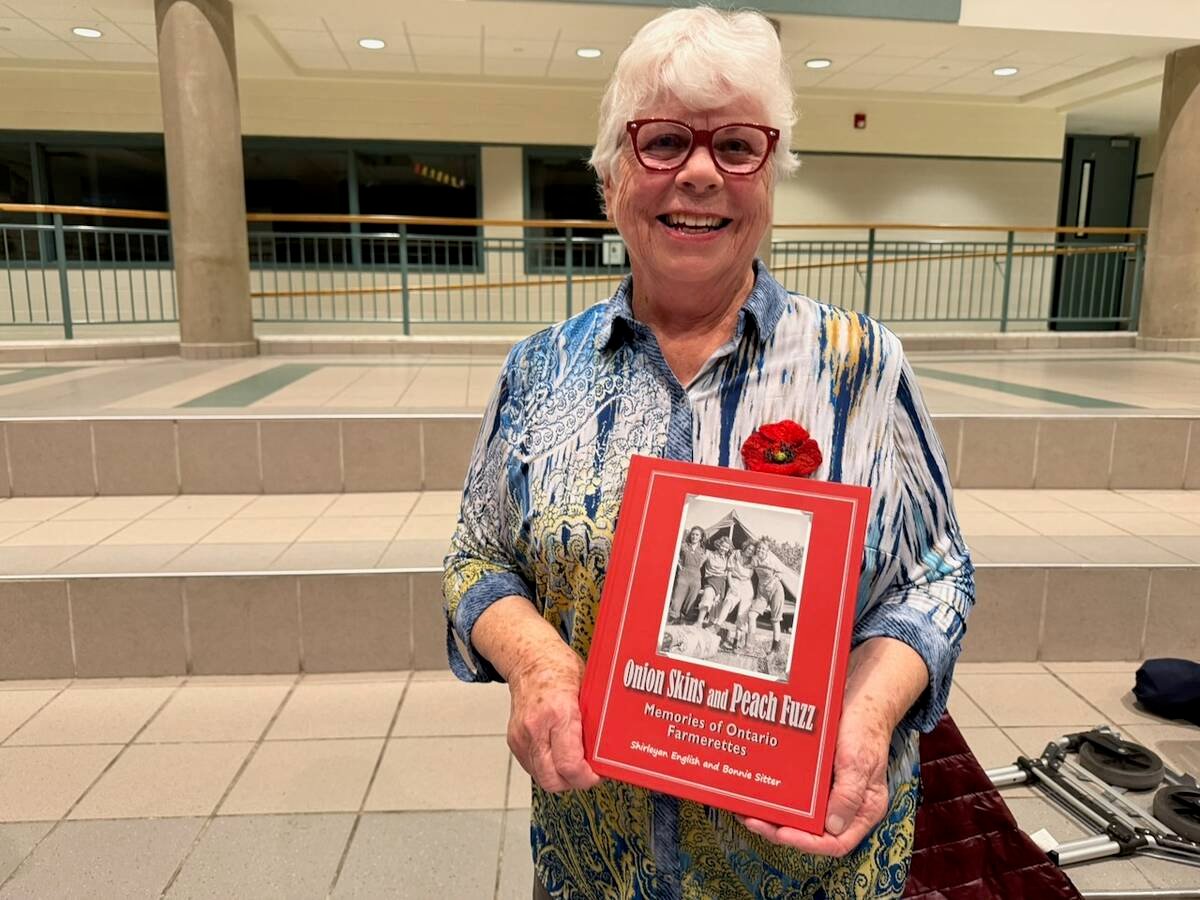

Read Also

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

The recent sale to Asian interests of Hylife Foods, a Manitoba-grown vertically integrated hog production company, is a modern manifestation of the same approach. They didn’t come here to buy pork. They bought the whole supply chain.

In fact, agricultural policies and regulatory structures over time have largely been aimed at supporting exports as an economic growth strategy.

Canada is now the fifth-largest agricultural exporter in the world, aiming to become the second-largest by 2025. We export half of our beef, 70 per cent of our soybeans, 75 per cent of our wheat, 90 per cent of our canola and 95 per cent of our pulse crops.

That’s not to say Canadians aren’t well fed. However, Canada only produces 70 per cent of its food supply domestically and it imports 80 per cent of the fruits and vegetables its citizens consume.

Our competitors such as the United States and the European Union have well-defined food policies that place the interests of their citizens first.

Canada, now more than 150 years old, is learning the details of its very first National Food Policy released this month. No one expects that policy to take the focus off agricultural and processed food exports, but it may open the door to a broader dialogue about strategic objectives.

There is cause to rethink our almost singular focus on export growth as the global trading environment becomes increasingly volatile and subject to political disruption.

That unpredictability leaves Canadian farmers and the economy in general vulnerable to the posturing by much larger economies that can balance their exports against a more robust domestic market.

As Canadians, most of us identify closely with the humanitarian imperative to accept new people. We also talk about the need for people that have the training and skills needed to support a shrinking workforce. The federal government says newcomers could grow the Canadian population by 340,000 by 2020.

Growing this country’s domestic demand for food and agricultural production is also an important strategic counterbalance to our export dependence.

In fact, the waves of immigration that settled the Prairies in the late 1800s started when politicians of the day decided that they needed people on that vast hinterland called the Prairies if they were to keep someone else from claiming it. The region was also a market for manufacturers in the East. There was really only one thing for those new people to do: farm, which is how Canada became known as Britain’s granary.

But again, the structure of the policies and programs of the day such as subsidized export freight rates, feed freight assistance and export certifications, sent that production away, instead of growing domestic processing and consumption.

As farming consolidated, rural Canada began exporting its youth to the point where it now faces critical shortages of people to do the work.

Recent announcements to help offset that, including the youth agricultural employment program and a recent announcement of a pilot project designed to place more new Canadians in rural communities, are important steps to offset those declines. But they aren’t nearly enough.

Canada has almost everything it needs to be a global superpower. It has the resources, it has the land base, the productive capacity and it has good government.

To succeed, however, it needs to focus less on being a granary and more on becoming a home.