My family bred polled Holsteins for 30 years, working away in fits and starts carefully crossing the limited number of polled families in the breed.

In the last few years of his dairy career, until the cows were sold late last year, my father put greater emphasis on the trait, using mostly polled bulls in the herd. There were lots more polled bulls available by then and it was possible to breed mostly polled without too much inbreeding.

One year there were only a couple of cattle born on the farm with horns.

Read Also

Packer buys Green Giant, Le Sieur veg brands from U.S. owner

A Quebec-based processor’s deal to buy the Green Giant and Le Sieur packaged and frozen vegetable brands in Canada from a U.S. owner clarifies the status of two popular retail brands grown by Canadian farmers.

It was a labour of love and curiosity. It’s always good to have something interesting to look to beyond the normal operation of the farm.

Breeding polled animals was a slow process and even though the polled trait is dominant, it took a long, long time to get anywhere with it.

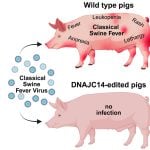

A deal was signed recently between Semex, the leading dairy genetics company in Canada, and Recombinetics, an American genetic engineering company, to edit the genes of dairy cattle to eliminate horns.

Semex’s herd of bulls and heifers and cows won’t be all polled soon, as there are some serious regulatory gates to path through, but this technology will make the years my family spent breeding polled Holsteins redundant.

It feels a bit weird to say that, but the polled genetics in our family’s herd, despite adding a functional and useful trait to the high classification cattle, were still just a novelty and brought little value in the end when the cows were sold. There’s also little doubt it narrowed genetic progress on other traits.

Something’s changed in the valuing of dairy cattle, with less emphasis on longevity and quality and more on how much milk can be produced that day, that week or that month, with the contribution calculated on return that day versus over years.

It’s a typical story of disruption by technology. We are seeing more of these, as technology begets new technology at a rapid pace. Most of these stories are positive, and if the developer is smart about what they are doing, then their product will have economic or societal benefit.

There’s little arguing against a simple, inexpensive (to the producer) process that means one never has to worry about horns again. It achieves clear and certain animal welfare and people management goals. Eliminating the (minimal) stress of dehorning has to help calves.

There’s all kinds of potential in gene editing. Polled is an easy first step, with a well-known, simple, gene location and a positive outcome for animal welfare. Finding other traits to change via ‘editing’ will come in time, but the real wins will be for disease resistance, boosting immunity and longevity, resulting in more milk production (or efficient meat growth).

We’re surrounded by constant technology innovation in agriculture. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be vigilant about their impacts.

At the recent Arrell Food Summit, I was in a session on data and artificial intelligence in greenhouse production, where a research scientist at the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre talked about how rapidly a technology is adopted and who has access to it. As farms grow larger and companies focus greater resources on those larger farms (something I’m already hearing irks average-sized farms), there’s the question of who gets access quickest. Which farms get the best livestock or fruit genetics first? Which get the newest sensor, or the ability to adopt a new tillage tool first?

I know some shrewd and successful farmers who never want to be on the ‘bleeding’ edge of technology, but are poised for adoption just behind it.

Adoption speed can have an impact on who has access, said David Gholami, the Vineland scientist, and the question has to be answered at some point about the speed of introduction and what that means for an entire sector.

We aren’t good at predicting how new technologies are used, and that’s a great thing. It means we are a flexible society and economy open to new ideas. But it can sure create stress and surprise when technology makes your work redundant.