In this final instalment of a four-part series on the Brantford Massey Ferguson combine plant (read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3, here), the story wraps up with a look at the plant’s final days and what was left unfinished as Massey Ferguson abandoned combine manufacturing in the 1980s.

As the 1980s began, the evolution toward fewer but larger farms had taken hold. That meant farmers were now buying fewer but larger machines.

Many executives in the industry, and especially at MF, failed to recognize this change early on.

Read Also

Agco worries about outlook for North America

Agco chief executive officer Eric Hansotia recently had both good and bad news to share about the demand for new farm equipment.

Added to that was a world-wide recession and record high interest rates, along with low commodity prices for farmers.

The impact was inevitable.

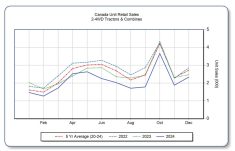

Overall combine sales reported by all brands in the U.S. in 1979 amounted to 32,246 but by the end of 1985, those numbers fell an astonishing 74 per cent to just 8,402. By then, sales numbers for the domestic market in Canada weren’t much better, nor were they anywhere else in the world.

By 1984, MF losses since 1977 exceeded $1.4 billion, and it had bank debts in 1980 of $1.6 billion.

In a 1984 speech, Victor Rice, MF’s then chair and CEO, said: “We went back to square one and asked ourselves: are we manufacturers? Are we marketers? Are we deal-makers? In the end, we decided we are marketers first.”

It was clear MF no longer believed it had to build the machines it sold.

The company was bleeding red ink, and things had to change quickly. The creation of Massey Combines Corp in 1985 was a big part of the effort to stop the hemorrhage.

In 1985, Massey Ferguson reorganized itself into a number of divisions, and sold off its combine business, including the Brantford plant.

To do that, it created an independent company called Massey Combines Corp (MCC) and gave it all the MF combine operations. In doing so, MF eliminated its largest money-losing venture and shed a large portion of its debt.

“A renewed company has emerged, poised for greater profitability, determined to create value for shareholders.”

That quotation was emblazoned across the cover of Massey-Ferguson’s 1985 annual report. But whether the extensive reorganization would lead to greater value for shareholders remained to be seen. One thing seemed certain, though. MCC, which was created to accommodate the renewed company structure, faced a tough go of it.

Dick Brown, MCC’s vice-president, put forward an optimistic face. He said during a media interview in 1986 that he expected combine sales in the U.S. to rebound to around 21,000 units.

It didn’t.

From the start, MCC had a staggering debt load. MF had pared off assets worth about $296 million to create the new company, but along with that it transferred over $206 million in long-term debt.

MF retained a $32.2 million stake in the new company, allowing it to profit in the unlikely event that MCC actually made money.

But despite the economic difficulties that the Brantford combine production faced in the 1980s, some exciting research projects were underway. Before the creation of MCC, MF’s rotary combine project, the TX900 that was initially proposed in 1976, was still progressing and MF had gone back to work on its conventional models, too.

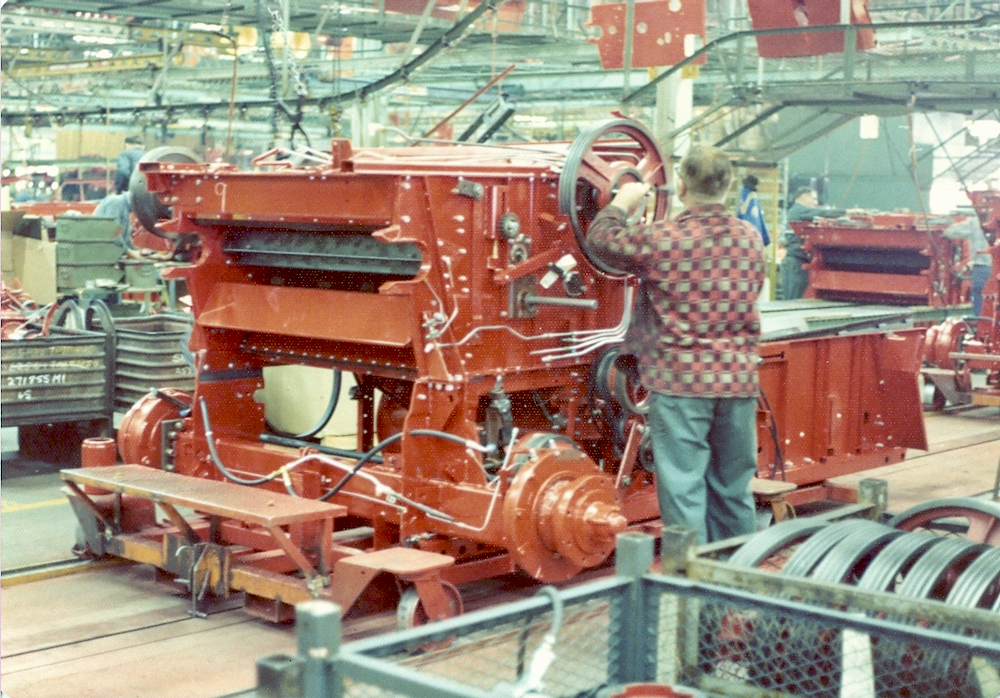

Starting in 1980, the TX800 project began, which was devoted to developing an entirely new conventional combine. The plan was to create a line consisting of four models designated TX801 to 804. These machines would have cylinder widths of 40, 50, 60 and 70 inches, respectively. And they would incorporate several new design elements over the previous 800-series machines.

The TX800 prototypes were hand built in the Harvesting Engineering Centre in Toronto and sent to Nebraska for field trials. They still bore some resemblance to the earlier 800-series models, but the cab had a new shape, as did the engine compartment.

Under the sheet metal there were other major changes. The new look around the engine compartment incorporated a redesigned air intake arrangement. The new combines would use 1000 Series Perkins diesel engines and a higher-performance drive train.

The drive train upgrades included a hydrostatic transmission with a high-capacity pump that was connected to a belt-driven, torque-sensing traction drive system.

At the same time, the rotary TX900 project was continuing, and it had been under development for much longer than the TX800.

Initially, the plan was to include three models in the TX900-series, the 901, 902 and 903. The 903, with its 27-inch rotor, was seen as the potential replacement for the 750 and was the main focus of initial engineering efforts.

One of the most innovative features on the 900 machines was to be incorporation of a load-sensing hydraulic system for the threshing rotor. It was intended to use hydraulics to maintain the correct concave setting to accommodate varying load rates and prevent plugging.

The 903 and 904 designs, though, hadn’t proven to be everything hoped for. They were prone to an unacceptable fore-aft pitching problem so significant design changes had to be made.

And engineering department estimates forecast that development costs in 1981 would reach $3.453 million. Testing on the 904 was originally expected to last until 1984 with the 903 completed in 1985.

Eventually, financial considerations would result in the both the TX900 and TX800 projects being dropped in 1985. But this time it wasn’t just MF’s financial problems that were the cause. It was White Farm Equipment’s bankruptcy, another victim of the farm-economy crisis.

Coincidently, White Farm Equipment was building a rotary combine in Brantford, too. To disperse the company’s assets, the receiver handling White’s bankruptcy offered to sell the White rotary combine to MF, before it splintered off the Brantford plant to MCC.

Management at MF decided it would be more cost efficient to buy the White design and put that into immediate production than continue developing its own.

Faced with all that, the TX900 project was dropped; and at the same time, so was the new conventional TX800.

MF was putting all of its combine eggs in one basket, the White rotary.

For a while, MF even marketed some White 9720 rotary machines with both WFE and MF decals on the side. Boasting that they now owned the White combine was a key part of the company’s initial advertising. And the 9720 was a giant for its time, powered by a 10.5-litre Perkins V-8, it had a 31.5-inch diameter rotor.

Eventually the dual badging of WFE and MF on the 9720 would end, and MF developed modified versions of the smaller White models that they numbered 8560 and 8570.

Production of the White rotaries continued at Brantford under MCC ownership, but by 1988, MCC had accumulated debt worth $90 million more than its estimated asset value. It was bankrupt.

After MCC failed, the White-based combine technology was put on the open market again. It was bought by Vicon, a Scandinavian company that had a small manufacturing plant in Portage la Prairie, Man.

Vicon had been manufacturing implements there, which were marketed by Canadian Cooperative Implements Ltd. It then sold the combine line to auto parts manufacturer Linamar, which had been supplying production parts.

MF stepped up and bought back the conventional combine business for the bargain price of $8 million from the bankruptcy receiver. That included plant tooling and inventory, but not the Brantford plant itself. This allowed MF to take back the lucrative parts business for the existing conventional combines already in service.

As for the Brantford plant, after nearly 175,000 conventional combines went down the assembly line, along with a much smaller number of rotaries, it closed and it would never again see combine production.

Brantford was a plant built to include room for expanding production and upgrades in technology, and was meant to last well into the future. A.A. Thornbrough, MF’s president who proudly posed for photos with dozens of dignitaries on opening day in 1964, probably could not have imagined his flagship factory would have a life of barely 24 years.