This is the second instalment in our series on the history of Massey’s Ferguson’s combine assembly plant in Brantford, Ont.

The early 1970s were good to Massey-Ferguson’s shareholders, and the Brantford combine plant was working flat out to meet demand for its combines. The 410 and 510 had catapulted MF to the front of the pack when it came to combine sales in North America.

In its 1975 annual report, Massey Ferguson said the previous five years (1971-1975) saw “unprecedented growth in the farm machinery industry. For Massey-Ferguson, demand in most markets exceeded production capacity in three of the five years.”

Read Also

Gap in emissions regs hamstrings Canadian hybrid truck manufacturer

In case you haven’t heard of it, British Columbia-based Edison Motors is a start-up heavy truck manufacturer. Being a startup…

But despite its success with the 10-series models, MF’s combine engineers weren’t sitting on their hands. By as early as 1967, work had started on yet another line of conventional combines that would replace the 410 and 510.

The 410 saw its last year of production in 1972, and shortly before the last 410 was built, in 1971, MF brought a new combine to the market: the 760.

The 760 boasted a 60-inch cylinder, making it by far the largest combine MF had ever offered. It was powered by a Perkins 354 cubic inch engine, and its 180-bushel grain tank allowed longer periods between unloading.

One of the features MF introduced on the 760 was a series of five paddle elevators that replaced the feeder chain and moved grain from the table to the cylinder, a unique option offered only on MF machines at that time. It helped even out the material before it entered the threshing cylinder, which improved efficiency and capacity.

Although the control arrangement inside the cab was similar to that on previous models, the cab offered a better working environment, with air conditioning available.

The Brantford plant came into existence in part due to the Second World War. The shortage of equipment and manpower to harvest grain across the North American plains during that conflict was a pressing problem, leading to the creation of a free trade agreement for farm machinery between Canada and the U.S.

With that free movement of equipment across the border, the Harvest Brigade was established. It followed threshing crews northward from Texas to Canada to harvest crops with Canadian-built Massey-Harris combines.

By the 1970s, MF was still actively involved in supporting custom harvesters, which by then had become a fixture in North American agriculture. But now MF wasn’t alone in that support. Most major manufacturers were making the annual migration northward in support of the many custom cutters who used their machines.

“It really was a mobile service and support entity,” said Kerry English, an MF engineer who started working with the brigade in 1974.”It started in Texas in the middle of May, in Wichita Falls.”

Why Wichita?

“It had an airport there, allowing the flying-in of people and parts,” he explains. After the harvest began, any required parts were flown in from the Dallas, Texas, parts distribution warehouse until the brigade had moved too far north.

Then parts were accessed from Denver, Colorado, and flown to other airports nearer the brigade’s location.

The brigade came under MF’s product integrity department. Engineers from various sections participated on a rotating basis, spending two weeks on the road and then being relieved by others.

“It was labour intensive,” recalled English. After returning home exhausted from nearly non-stop activity, he remembers feeling he didn’t want to ever go back, but that sentiment always seemed to fade.

“It gets in your blood,” he said. And engineers often looked forward to another tour of duty.

Keeping a fleet of roughly 300 MF combines belonging to about 50 custom cutters, who worked continuously, created a sense of accomplishment for members of MF’s support staff, and providing support to custom operators was good for MF’s engineers.

“The brigade was an exceptionally good vehicle for monitoring the performance of new machines,” says English. “But it was hard work.”

He remembered it wasn’t unusual to work through all hours of the day on emergency repair operations. And when the weather was good, only bad weather stopped the combines.

“I remember a cutter came to the trailer one particularly dry year, and they hadn’t had a day off in 43 days. They were hoping for some rain to give the crews a break,” he said.

And if the cutters didn’t get a break, neither did the MF engineers.

MF’s brigade program was primarily geared toward new combines still on warranty. But the engineers helped whenever they could, even with older machines. Relying just on existing dealers wouldn’t have been practical for most custom cutters.

“Few dealers in those areas were structured to have the support and parts to handle them,” said English.

Many smaller community dealers would have been overwhelmed by the demand for parts and service when a large group of cutters invaded the countryside around them.

“No dealer could afford to have that inventory for the two weeks the cutters were around,” said English. “The brigade route often planned stops in areas where dealer support was weak to help alleviate the problem.

“Cutters used to say that if it hadn’t been for the harvest brigade, they would have used some other brand,” English recalls.

So, maintaining its presence on the brigade trail was critical to MF’s domination of combine sales. And although other manufacturers had their own version of the harvest brigade, they failed to recognize its importance to sales as early as MF did.

At the start of each season, MF would publish a brochure outlining the route of the harvest brigade service group for the year. Although it was firmly established, the timetable was not. When the custom cutters moved north, so did MF’s support team, and that movement depended primarily on the weather. The team had a semi-trailer truck stocked with about 2,000 combine parts.

“We took everything we thought we’d need,” says English. “Usually, the team had the parts on hand for repairs, but occasionally they would have to order others in. To fan out and cover the widest possible area, an engineer in another vehicle would follow a parallel route northward.

“There was a van in addition to the semi-trailer,” he said. “We used to call it the satellite. It would follow a slightly different route and it ended up in Great Falls, Montana at the end of the season. The main team of engineers would finish up in Mandan, North Dakota.”

The 1970s was a turbulent decade. The oil crisis, high interest rates and falling farm commodity prices were clouds that loomed on the horizon for the Brantford plant and MF — and everyone involved in agriculture.

Nevertheless, MF’s gross sales had risen from $1.192 billion in 1972 to $2.925 billion in 1976. Net income had been rising too, increasing nearly fourfold during the same period. But then things began to change.

Barely two years later, in 1978, MF’s net income had fallen off a cliff. The company lost $257 million and its debt was climbing, which was eating through MF’s working capital at a record pace. It fell by nearly half from the beginning of 1977 to the end of 1978.

Massey also shed nearly 10,000 people from its workforce during the same period. The financial storm had started, and the Brantford combine plant was squarely in the middle of it.

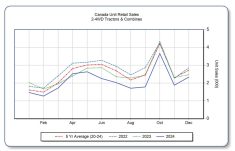

Combines accounted for 12 per cent of MF’s sales, but U.S. figures for combine sales were showing rapid decline — much faster, in fact, than tractor sales, which were also falling.

In the U.K., MF was increasing market share but falling farm commodity prices meant overall sales figures for combines were way down.

Canadian sales figures were the one bright spot for combines through to the end of the decade, but this was not a large enough market to sustain production levels at the Brantford plant. Worldwide, combine sales were falling faster than any other MF product.

At the close of the decade, despite a worsening financial situation, MF was still ready to keep pace with the competition. The 700-series combines were due to be replaced by updated versions, the 850 and 860 models, which would hit the market in 1981.

And since 1978, MF’s engineers had been busy working on the TX900 project, a new machine that represented a radical change from MF combines of the past: a rotary combine.