Updated Oct. 22, 2025

Imagine holding out your phone to a cow and having an app tell you the meaning of their moo?

The technology isn’t quite there yet, but it’s close, and an app recently released by Dalhousie University researchers can help train farmers and workers on what’s actually in a moo.

Read Also

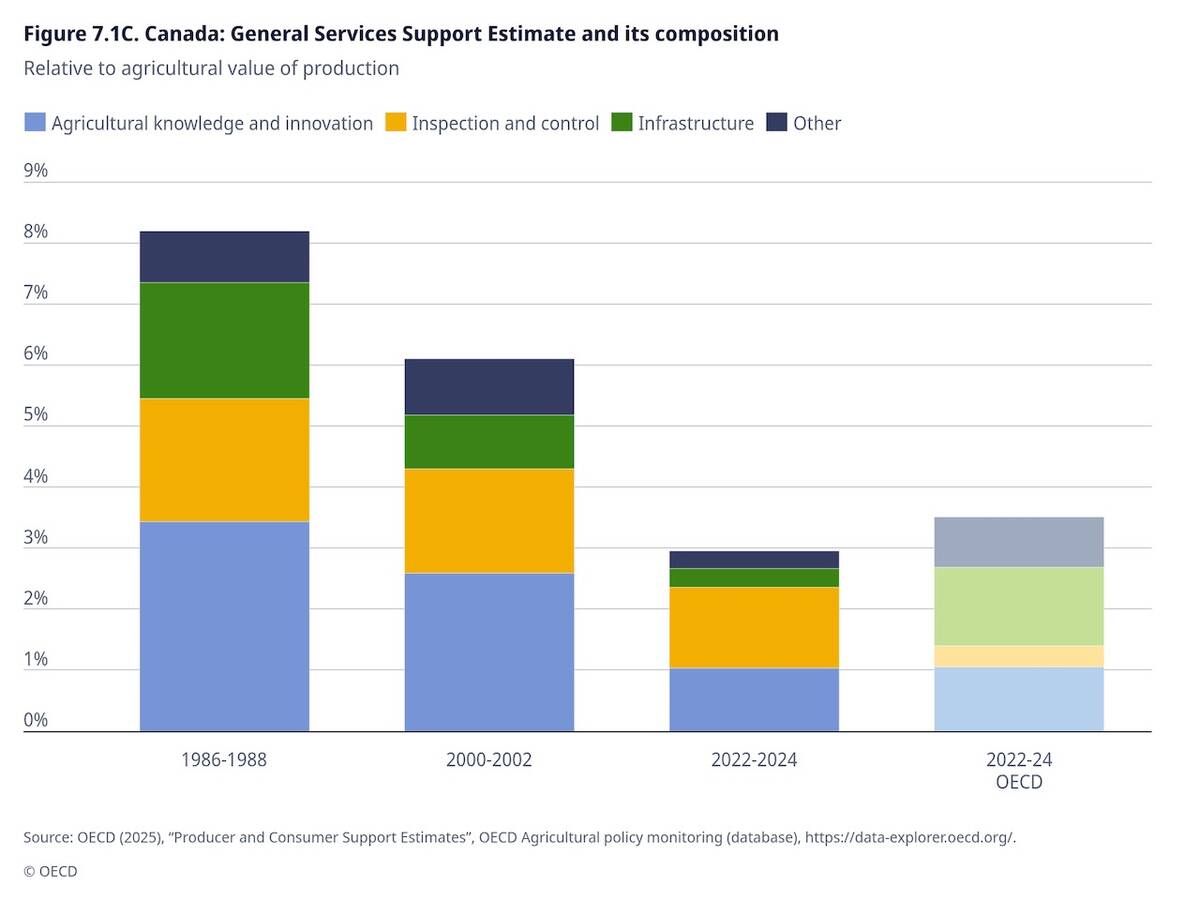

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

Why it matters: Artificial intelligence is helping to process large volumes of data, creating resources that farmers have never had access to before.

The MooLogue app is one of two apps recently released by professor Suresh Neethirajan and his Mooanalytica research team at Dalhousie University.

The other app, called DairyAir Canada, quickly allows a farmer to assess the methane production on their farm over the past 15 years.

Both apps give a sense of the powerful tools that can be developed due to the advanced processing capabilities of artificial intelligence.

Neethirajan said MooLogue can give someone who hasn’t worked in agriculture before, or who may have worked on a livestock farm such as swine or poultry and is interested in working with cows, an early understanding of what they’ll hear in a dairy barn.

Developing the data behind the MooLogue app involved old-school research, however, as students installed sensors and recording devices at about 13 farms, at eight or nine locations on the farms — from calving and milking areas, to stalls and dry cow areas.

They collected many hours of vocalizations, then used artificial intelligence to compare the audio and the video that went with it, to connect the sound to what was happening in the barn, said Neethirajan, who has a joint appointment in the faculty of computer science and the faculty of agriculture.

The researchers connected the frequency of the moo and duration with events in a cow’s day.

When a mother cow is bonding with her calf, she will moo at about 120 to 280 Hz, low-frequency murmurs that last up to 2.5 seconds.

When a cow is in distress, its calls will be more urgent, at 600 to 1,200 Hz and will exceed three seconds in duration.

The researchers can now tell when cows are about to be fed, and when the cows are greeting each other. They can also tell when they are in heat.

Most experienced farmers can also combine the auditory signals from cows with what they observe in the barn to come up with similar conclusions about the state of a cow. Indeed, the team validated the sounds and results with experienced farmers.

However, with increasing numbers of farm employees coming from off the farm, these sounds can be used for training, as the app is currently set up to do.

“They can play with the app to better understand,” said Neethirajan. “This is a hunger call. This is frustration. She is going through heat.

“If there is a veterinary student, if they want to handle the cow without going and touching them, handling that animal, they can play with the app as a preliminary step.”

Future products could include what Neethirajan refered to as a “black box” that could sit in the barn and record sounds, process those sounds and provide a report to the farmer remotely or when she is back in the barn.

One of his doctoral students is working on a cow translator, using natural language processing, figuring out how to turn a moo into something that accurately fits human languages.

When cow frustration was measured in 300 different contexts, “we were able to see patterns, specific letters and specific words started emerging, constantly coming in that particular context.”

Another step is to see what other breeds have to say. Holsteins were used as they account for most of the animals on Canadian dairy farms, but there’s some work being done on beef cattle. It’s more challenging however, because beef breeds and other cattle in other parts of the world aren’t housed indoors.

Monitoring methane

Methane released by cow burps after digestion and manure pits is one of the leading concerns around climate change related to livestock farming, but there have been few tools to measure and monitor individual farm methane output.

Neethirajan’s Mooanalytica lab has released the DairyAir Canada app, which can show each dairy farm in the country their methane release trends from Jan. 1, 2010 to Dec. 31, 2024. The methane is not tracked in real time.

The research team used data from three different satellites, including NASA’s Terra, Europe’s Sentinel-5P and Japan’s GOSAT. The data was then parsed and smoothed, so that each farm had a rating.

The app isn’t just a snapshot, it also allows farmers to compare their data to others within a 50 to 100 kilometre radius, their own provincial average and a national distribution of methane emissions. They can do analysis based on seasons and can download reports.

Across the country, the results could be different based on management, climate and building design.

Neethirajan said this creates a benchmark for farmers. They can then take action, depending on what they learn.

Overall, Neethirajan said methane emissions have continued to increase on dairy farms across the country over the past 15 years. Some years Ontario was the leader, but other years Quebec had the largest emissions.

The research for the apps was supported by Dairy Farmers of New Brunswick, Dairy Farmers of Nova Scotia and government funding programs for agriculture.

Both MooLogue and DairyAir Canada are available for Apple and, as of Oct. 14, for Google devices.

Updated Oct. 22 to clarify research supporters.