Dairy farmers will continue to watch the effects of three trade deals roll out over the next six or more years and the future growth of the sector will depend on whether or not the sector continues its past growth pattern.

The most recent is the Canada-U.S. Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) that replaced the NAFTA deal.

The timing of the CUSMA deal effectively rendered the dairy year as only one month long in 2020.

“This increased access doesn’t mean it will all be filled,” says Sebastien Pouliot, senior agricultural economist with FCC in a presentation at Canada’s Digital Farm Show. The trade system is complicated and will be phased in over years.

“In the first six years it will be more difficult as there will be more products entering.”

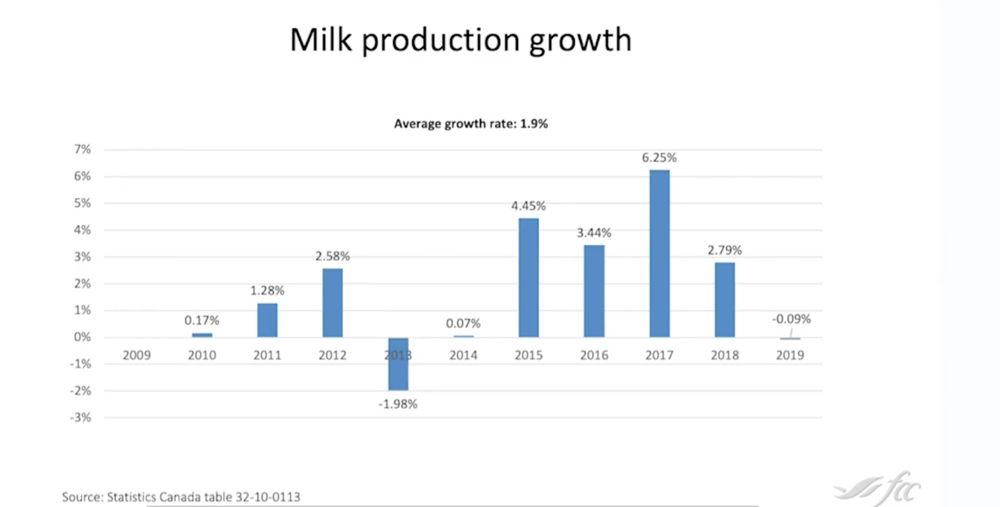

Over the last 10 years Canadian dairy production has increased 1.9 to two per cent per year. In six years, if that growth continues, U.S. influence in the market will then be in decline, says Pouliot.

Much of the growth in the market will be gobbled up by new imports, says Al Mussell, of Agri-Food Economic Systems, at Canada’s Digital Farm Show.

“If there’s three per cent aggregate growth in the market then imports get two per cent and we get one per cent. It could work something like that,” he says.

It will be six years before the CUSMA deal flushes through, says Pouliot.

“So even though we expect a negative impact on Canadian production over the first six years, after that it’s going to be less important and I’m optimistic that things are going to get better for Canadian production afterward,” he said.

The elimination of Class 7 is also a major impact. The class, which was used to competitively price non-fat milk solids, has mostly been eliminated in the CUSMA deal and the products will now go into Class 4A, which used to be the class for butter and milk powder.

Read Also

Ontario’s agri-food sector sets sights on future with Agri-Food 2050 initiative

The first-ever Agri Food 2050, a one-day industry event dedicated to envisioning the future of food and farming in Ontario,…

“We don’t have a disaster here with Class 7,” says Mussell. “It’s something that can be accommodated. I think we have some flexibility to accommodate it.”

Prices for non-fat solids and baby formula can’t be lower than the U.S. price, according to CUSMA rules.

However, Pouliot says in some cases that could mean an increase in prices for non-fat solids in Canada. There will also be an impact on how Canada can export these products and that’s not yet known.

Some non-fat milk products that were once exported might have to stay in Canada due to CUSMA-created export limits. They might have to be priced lower in another class such as 4m (which is a low-price class for dairy products into things like pet foods) or Class 5.

The way that the CUSMA agreement is written has some wondering if it will still make sense to export milk protein concentrate, even with the tax for above-limit exports, says Mussell, although Canada has limited capacity to process milk protein concentrate.

The amount of skim milk powder and protein concentrates exported in each of the past three years will be over the 35,000 tonne limit imposed by CUSMA and about 30,000 tonnes would have to stay in Canada.

However, if Canada is exporting less, it will be importing less, as those products have to find a home in Canada and could be priced lower domestically versus imports. Even so, Pouloit said, “we expect that there will be some quantities of skim milk powder and infant formula that will have to go to industrial uses.”

Exchange rate value – an important factor in commodities such as grains and beef – will have increasing importance as Canada has to match volumes at an American price for exports.

Two other trade deals recently granted access to the Canadian dairy market and their impacts are starting to be felt.

Quotas that allow more dairy imports from Europe though the CETA agreement are being filled, mostly for cheese, said Mussell.

The Comprehensive Progressive Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) opens the market to a much larger group of dairy products. However, Mussell says some of them, such as for bulk milk, were aimed for the U.S., which later pulled out of the deal. Some of that market access could be unfilled, but there are many others for skim milk, butter and cheese.

Altogether, there’s about 10 per cent market access on cheese among the three agreements. There are other categories that will be 14 to 15 per cent access.

That’s a significant amount, says Mussell.

While dairy farmers will be affected, with less of the Canadian market available to fill with Canadian milk, processors also will be constrained, says Mussell, with fewer export markets.

Canadian processors had invested hundreds of millions of dollars in recent years in upgrading plants and a more restricted environment will be challenging for them too.