Organic growers in Ontario interested in trying no-till soybeans might want to call the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association (OSCIA).

After a three-year, multi-site assessment of the practice that allowed field trial hosts to use one of two specially designed “roller-crimpers” purchased by OSCIA, those implements are now available for growers to try.

Those interested should remember that results from those three years of trials indicate profitability may suffer and chances are high for significant yield losses due to weeds.

Read Also

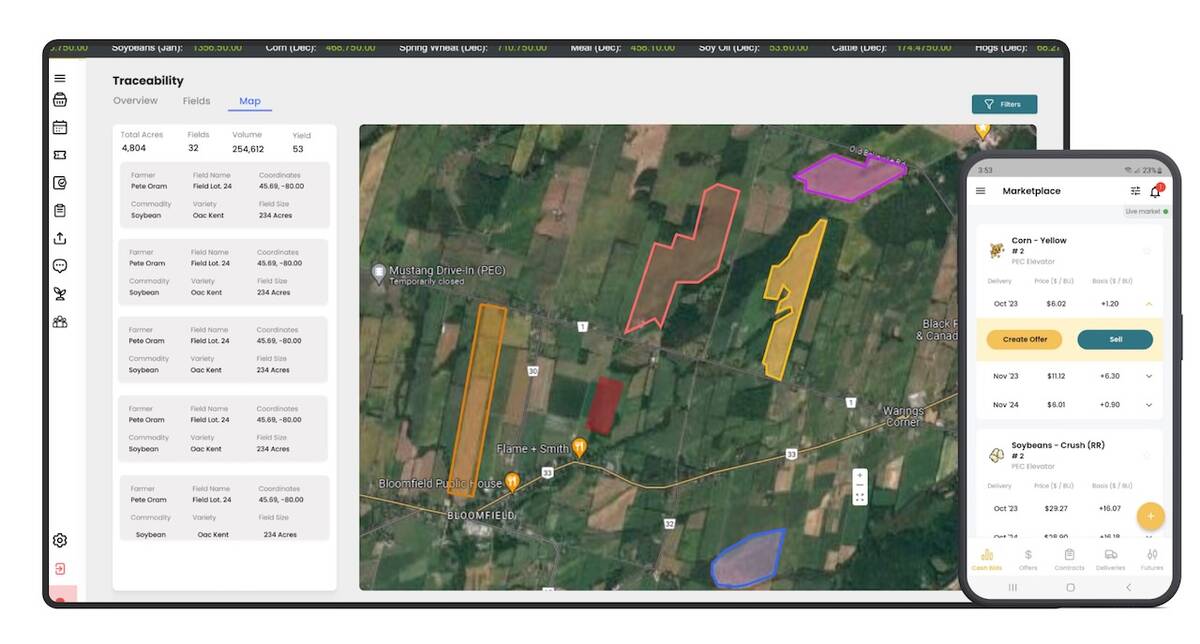

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Why it matters: With rising fuel costs, organic growers may be looking to reduce tillage typically used for weed control in soybean production.

The trials conducted by OSCIA studied the practice of planting soybeans into a rye cover crop (established the previous fall), either immediately after or immediately before it is rolled and crimped in the spring. In a March 14 report for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) Field Crop News, OMAFRA Soil Management Specialist Jake Munroe said the practice “is not yet recommended on a large scale.”

Munroe, who was supported by OSCIA and the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario in leading the 2019-2021 assessment, said that doesn’t mean the practice will disappear.

“There’s no beating around the bush. The yields aren’t equal to standard management, either with herbicides or with conventional tillage under organic management,” he told Farmtario.

With average soybean yields of approximately 36 bushels per acre, the roller-crimped rye sites had the potential for profitability in both 2019 and 2021, given the organic premium paid. But plots under organic management using conventional in-row tillage for weed control were considerably more profitable, with yield boosts of five to 10 bushels per acre.

In 2020, profitability on the roller-crimped sites was marginal at best, with an average yield of just 26.6 bushels per acre.

This may speak to the strengths versus the weaknesses of the system compared to in-row scuffling. In dry years, said Munroe, there may be insufficient moisture in many Ontario soils under organic management to fully support a rye crop in spring followed by a soybean crop through summer.

But in wet years, such as 2019, that thick mulch of crimped rye can suppress late spring/early summer weed growth, considering there’s limited opportunity in summer to get into the field and scuffle.

However, the biggest factor inhibiting profitability was getting a good stand of rye. Before the three-year trial began, Munroe cited northeastern U.S. research indicating a need for greater than 6,000 pounds per acre of biomass from the roller-crimped rye in the spring “as critical for successful weed suppression.”

Only a handful of the Ontario sites achieved that threshold over the three years.

“You really need to treat that rye cover crop like a crop,” he noted.

Rye had to be planted in early to mid-September to come close to the threshold. Any later than that and the system is almost certain to fail due to insufficient suppression of weeds.

If growers already have weed problems, Munroe advises them to deal with those before trying no-till soybeans. Also, make sure the field planted to rye has sufficient fertility to feed the cover crop.

The need for mid-to-late September planting, as well as the high risk of volunteer rye taking over a subsequent crop of winter wheat or spelt, makes the system unworkable in a typical three-crop rotation. Before the rye, growers must plan for early-harvested crops such as spring grains, sweet corn, silage corn or field peas. After soybean harvest, options include mixed grain under-seeded to alfalfa, edible beans or peas.

The short soybean growing season also hinders profitability, says Munroe. Not only must growers wait to plant soybeans until the rye hits the flowering stage – typically early to mid-June – but those soybean plants don’t grow as quickly after emergence.

Plants sprout into heavily shaded, cool air under a thick mass of roller-crimped rye, giving them at least a week’s delay in growth compared to conventional counterparts.

The three-year trial is complete with less-than-optimal yield and Munroe plans to undertake other research opportunities. Yet he’s not ready to give up on the practice. Working with two growers who plan to continue with no-till organic soybeans in their diverse rotations (Morris Van De Walle at St. Marys and Brett Israel at Drayton), he aims to test a new-to-Ontario rye variety bred for high biomass and early spring flowering.

“I will stay involved in this project in a small way,” said Munroe, adding he’s happy to field calls from producers who want to borrow one of OSCIA’s roller-crimpers.

“We’ve identified some areas for possible improvement. … I’m certainly not calling it a failure.”

Beyond that, he notes, there may be intangible benefits that make the system worthwhile. If used as part of a long, diverse crop rotation, growing the rye cover crop will sequester carbon and enhance soil quality. This will benefit crops later in the rotation, Munroe said.

Additionally, using the system can free up time for organic farmers at other points in the growing season. One grower in the field trials told Munroe he will continue using the practice because he was able to take a family holiday at a time when he typically would have stayed at home to manage the soybeans.