Sometimes new tech is employed for what some farmers dub “the cool factor.” For most, though, the adoption of precision farming strategies largely relies on a rather dogged question – namely, does it pay?

In many cases the answer remains elusive. This reality has been cited as a major contributing factor to slow rate of precision technology adoption rates among farmers throughout the more developed world.

That’s not to say, however, there are no answers.

Indeed, farmers presenting at the 2019 Southwest Agriculture Conference (SWAC) say determining return on investment (ROI) for precision technologies, like variable rate, is very possible – if one takes time to do the math.

Read Also

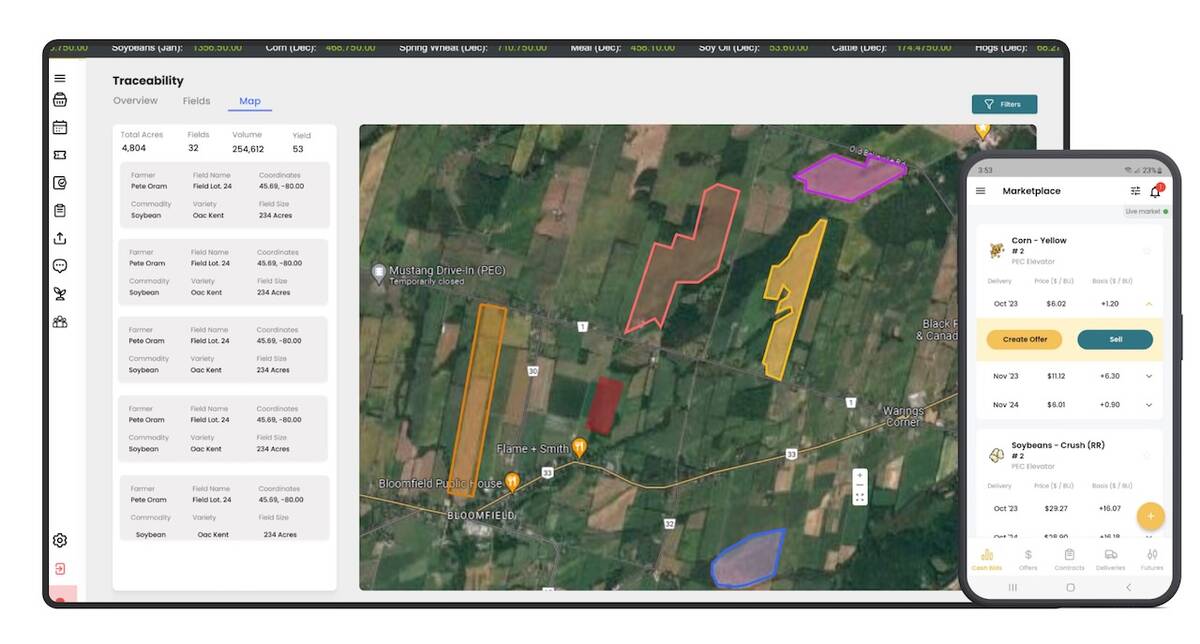

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Why it matters: Variable rate technology can increase profitability if good records are kept, and growing conditions are well understood.

The importance of record keeping

Chris Boersma, a precision agriculture specialist and grain, pea, and white beet farmer from Ridgetown, says proper documentation is critical in determining whether a precision technology is or is not providing a good return. This can be done either manually or through a data management program, though modern tech has made record keeping and availability much easier.

“The equipment doesn’t give you the refund. It’s the work you put behind it,” says Boersma. “It’s really more of a system […] everything adds up. You have to do the analytics behind it to make it pay.”

For his family’s operation, years of record keeping have proven vital in determining the effectiveness of, for example, variable rate nitrogen applications. By documenting applied nitrogen specific to individual coordinates within a field and overlaying that data with harvest maps – as well as running non-variable rate test strips – Boersma says they can reverse calculate what rates work best, and where their savings are.

He adds good records can’t be generated in a single year. Developing good data, and deriving useful information from that data, is a multi-year process.

“If you fill everything in, do it all, you have all your records in one place where they’re easy to access,” says Boersma. “It doesn’t matter whether on a phone, and iPad, wherever, but you can go back to the field, see where a certain variety or application is […] that is invaluable.”

Useful in variable growing conditions\

Like Boersma, Ann Vermeersch, an agronomist and row crop farmer from the Tillsonburg area, says determining the profitability of variable-rate starts with calculating the impact of input redistribution.

On her and her husband’s Norfolk County farm, variable rate lime application has proven particularly cost-effective for the past seven years.

Because of differing growing conditions on her farm – which she describes as “highly variable” in terms of soil type, drainage and elevation – Vermeersch says uniform lime prescriptions are rarely appropriate. Combined with the high volumes and costly nature of the input, she says the savings are both clear and consistent; similar benefits have been found with variable rate potassium and phosphorous.

They also began using the technology in soybean planting three years ago. More specifically, she says reducing the number of soybeans planted in good areas of the field – soybeans fill out well, making seed density less of a concern – has brought both a reduction in white mould issues and savings of $10 to $15 per acre in seed costs.

Vermeersch does think it’s less likely variable-rate would pay in more uniform field conditions, such as those predominating in counties like Essex or Chatham-Kent. In her case, however, it’s proven to be a very useful tool.

In terms of next steps, she says they want to investigate profit mapping in order to bring “an economic layer” to a field. By using actual costs for inputs and equipment, that is, better profit and loss calculations can be made across management zones.

“We live in a world of imagery. I’m still trying to make imagery work,” she says.