The Dynasty kidney bean has been named the University of Guelph’s 2024 Innovation of the Year.

A complex “conical” cross of four different edible bean varieties, Dynasty was first planted as an “F1 cross” in a growth room at the University of Guelph’s department of Plant Agriculture in 1997 and entered into provincial variety trials 10 years later.

It’s now the dominant dark red kidney bean grown in Ontario as well as Michigan and other edible bean-growing regions of North America, and is licensed by Hensall Co-op.

Read Also

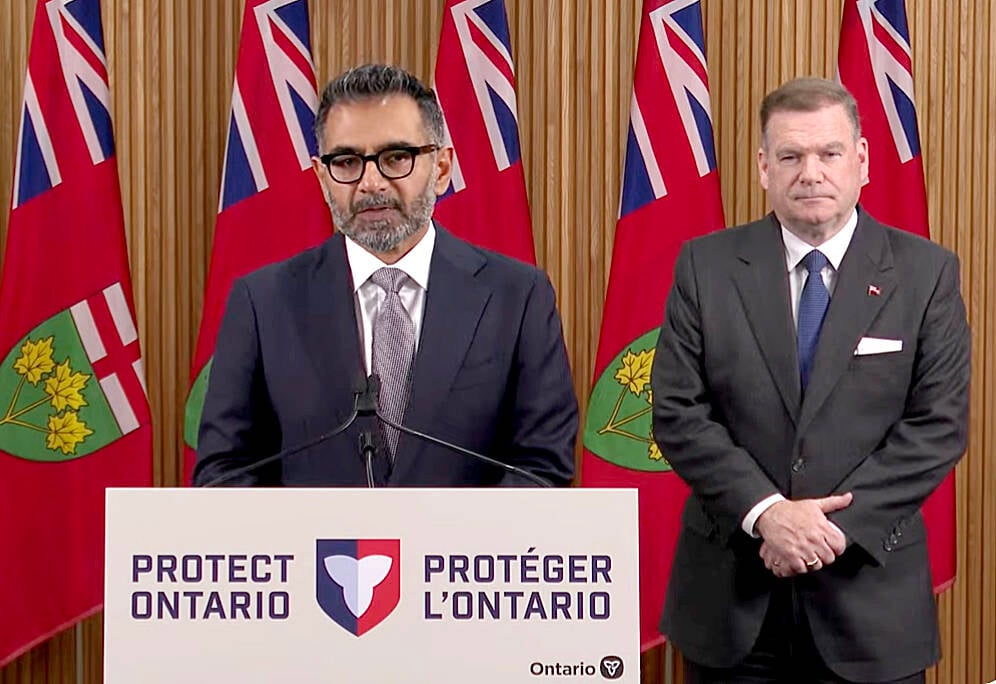

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

“It’s more than just a personal or professional accolade,” said U of G professor Dr. Peter Pauls, who accepted the award alongside department of Plant Agriculture research technician Tom Smith. “It’s a recognition of the broader ecosystem of support, infrastructure and people who make this work possible.”

Speaking to Farmtario, Pauls described Dynasty’s development as “a long-term effort with lots of people and resources coming together to bring (the variety) to the point of commercialization.” He noted early breeding efforts were led by former U of G professor Dr. Tom Michaels, now with the University of Minnesota.

He also praised Hensall Co-op for early support of the breeding efforts and eventually taking the risk of commercializing the variety. Collaborations with the provincial agriculture ministry at the Elora Research Station and other crop trial locations were crucial in allowing the variety to be grown outside the confines of a laboratory setting, he said.

Ontario Bean Growers (OBG) Chair Jamie Payton, who farms near St. Marys, described Dynasty as a game-changer in the province’s edible bean value chain. Speaking to Farmtario, Payton said a collective desire to maintain genetics with the potential to enhance profitability on Ontario farms led to a decision years ago for OBG to financially support U of G’s breeding program.

“And when a variety like Dynasty came along, there was no question that we had made the right decision.”

After Dynasty was named Seed of the Year at the 2022 Canadian Plant Breeding Innovation Awards (covering field crops, forages, fruits, vegetables and herbs), an article in award co-sponsor Germination magazine (now called Seed World) described Dynasty as “a complicated pedigree, having been derived from a double-cross between HR85-1885 and Montcalm, and USWA-39 and AC Litekid.”

The parents, Pauls explained, were chosen to bring in good cooking quality, disease resistance and what he referred to as “good plant architecture” – a combination of characteristics including standability and pod location that generally speaks to the ease and efficiency of harvest for the variety.

The first in-field trials for the double-crossed hybrids occurred at the Elora Research Station in 1998. That eventually led to the in-field planting of F-5 crosses in 2002.

The variety was entered into the Ontario Colour Bean Registration and Performance Trials in 2007, 2008 and 2009.

For the Colour Bean trials, harvested beans are tested for cooking quality at the Greenhouse and Processing Crop Research Centre in Harrow. The U of G team’s published results in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science showed it compared well for cooking quality and disease resistance with others in its class – including one of its parents, Montcalm.

But it also showed a significantly higher yield potential – 21 per cent over the mean among participating varieties. That increased to a 25 per cent yield boost compared to the others if a less-than-convincing first of three years of trials was taken out of the calculation.

Pauls notes that the U of G program runs its own yield trials leading up to a new variety’s participation in what are typically two years of Ontario government trials. From those early trials, the U of G breeders knew they had something worth exploring further.

But the yield results from the 2007 Ontario trials were underwhelming.

“We don’t know why,” he recalled. “Was it an anomaly? Was it badly placed within the trial, on a poor piece of ground?

“We wanted to not abandon it.”

So they re-entered Dynasty, then known as OAC07-6D1, into the provincial trials, giving it three years’ participation instead of just two. The variety’s true yield potential shone through in the second and third years of those trials.

“There are a number of different traits that control yield,” Pauls explained. “It’s something we call multi-genic” and, in this case, can include the number of pods, the number of beans per pod, the percentage of those beans lost during the harvesting process and other factors.

“All of these things coming together in an optimal way leads to a higher yield.”

“With a typical new variety, we expect to make gains in yield potential of one or two per cent,” he said. But with Dynasty, the first published trial results showed a greater than 25 per cent yield boost compared to other varieties in its class.

Now, several years after its entry onto the market, it still maintains an approximately 15 per cent yield lead over the next top-yielding dark red kidney bean in North America.

Pauls noted that Dynasty’s importance now extends beyond its role as a top-yielding, commercially successful edible bean variety. The U of G program has now used it as a parent in subsequent breeding trials. “It has become important for future variety development.”

Gallantry, a Dynasty offspring now also available on the market, matures slightly earlier and has a slightly smaller seed. Theoretically, this means it has less chance of getting knocked around during the harvesting process. Plus it maintains the Dynasty yield boost.

Will Gallantry eventually take over from its parent?

“Growers get comfortable with particular varieties,” Pauls offered. “They get to know their peculiarities and how to be successful with them,” so he believes it’s too early to tell.

But he stresses there’s an inherent risk if one variety takes over to the extent that Dynasty has. A highly virulent strain of anthracnose, for example, could potentially wreak havoc on kidney bean production in Ontario under the current scenario.

“It’s nice to have a dominant variety and it speaks to the success of the breeding program as well as the potential for future successes,” he said. “But in terms of the landscape and the genetic ecosystem, it could be better to have more genetic diversity.”

Still, he added, this is not corn or soybeans. Edible bean growing is inherently more risky than numerous other Ontario cash crops due to factors involving weather and harvestability. Realistically, kidney bean fields will never stretch uninterrupted across wide swaths of Ontario’s farm landscape.

Payton concurs that the introduction of Dynasty – with its significant yield boost and subsequent boost in per-acre profitability – didn’t suddenly turn the heads of every Ontario cash cropper, causing them to reconsider their crop rotations and add edible beans into the mix. He’s not even sure if the variety’s introduction added very much to total acreage in Ontario planted to kidney beans.

But what it did do was solidify the willingness of the province’s edible bean growers to stick with dark red kidneys, by giving them a dependable option for a market that has become increasingly competitive on a global scale.