Research at Michigan State University (MSU) aims to develop a test to determine alfalfa autotoxicity in a field, similar to tests for detecting residual herbicide that could damage a crop. That same research could lead to breeding varieties with resistance to the condition.

MSU Forage and Cover Crops Extension Specialist Kim Cassida covered the topic in her presentation at the recent 2021 Forage Focus conference, hosted virtually by the Ontario Forage Council.

Why it matters: Given the cost of alfalfa seed, growers want assurance their crop will thrive instead of be killed or damaged by residual effects from the previous stand.

Read Also

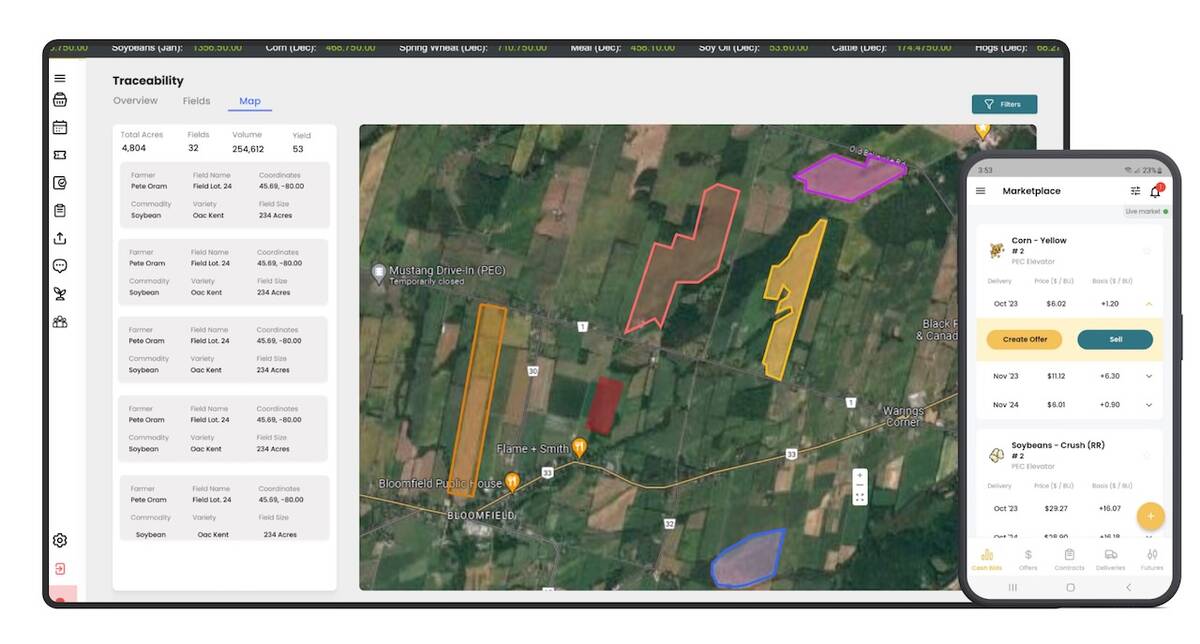

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Cassida reviewed an Ontario-based website that dedicated a page to alfalfa autotoxicity, which results in newly planted alfalfa either failing or doing poorly if planted too soon after termination of a previous alfalfa crop. The Ontario information highlighted medicarpin as the main culprit but Cassida challenged that assertion. She said it is just “one of the things in the mix” that give rise to autotoxicity.

“This is a problem we’re spending a lot of time on here in Michigan,” Cassida said. She showed side-by-side photos of alfalfa plants dug from plots planted 18 months after a previous alfalfa crop versus two weeks after termination of alfalfa.

The plants after the long wait time had solid, long and straight tap roots. Plants from the two-week wait time, by contrast, had three or four narrow, curly roots that didn’t extend as far below the soil.

“The plants have tried to compensate by making new branch roots but this is never going to be a plant that is able to produce as well as a normal plant,” Cassida said.

She also showed photos of plots planted after several years of continuous corn versus a single year of corn following a previous alfalfa crop.

“If you were to just look at this field (with one single year of corn), it might look OK” on its own. But shown beside the other plot, the difference in seedling vigour was obvious.

Cassida conceded that a single crop of corn between two crops of alfalfa is generally accepted as an effective strategy to eliminate autotoxicity. Even fall termination of alfalfa followed by a winter fallow period and re-establishment in the spring has proven effective.

However, the single-crop corn waiting period in the MSU research plot came during a drought year, and adequate rainfall along with tillage plays a role in boosting microbial activity that can break down the autotoxicity-causing chemicals more quickly than in dry years or under no-till conditions.

So far, all researchers can say for sure is that an unknown mix of water-soluble compounds makes alfalfa toxic to its own seedlings for an unknown length of time after termination of the previous crop. Factors include farm-scale realities like soil type and precipitation, as well as “things that are management-dependent, that we can control a little bit,” such as the age and density of the previous stand at the time of termination, the variety, and the time lag after termination.

Given that the condition affects “anybody who grows alfalfa,” Cassida said she is encouraged by a recent surge in U.S. research into autotoxicity.

She highlighted University of Iowa lab work in which alfalfa was planted within eight-inch and 16 eight-inch radii of established alfalfa seedlings. Within eight inches, or about 3.5 crowns per square foot, there was little growth. Within a 16-inch radius (about 1.4 crowns per square foot), “they had plants but they were not performing very well.”

She said this is textbook “auto-conditioning.” It’s a form of autotoxicity in which the subsequent stand does grow but is of poor quality.

The generally accepted standard for replacing alfalfa to retain profitability is five crowns per square foot. So “with either of (the eight-inch or 16-inch radius) situations, you have a crop of alfalfa that is well below where you would start to think about replacing the stand.”

In the Ontario climate, with usually consistent rainfall, somewhat less than a year of wait time after termination is probably suitable, she said. She’s not a fan of fall termination followed by a winter fallow period and re-establishing in the spring but she supports either growing corn and waiting until the following spring for alfalfa, or oats/peas as a spring crop and replanting alfalfa in late summer.

Cassida knows the recommendation that a failed alfalfa crop can be followed quickly by replanting. But if that is the decision, she advised, do it early. If any of that failed crop has been allowed to flower, she has seen enough in-field evidence of autotoxicity to advise caution.

Ideally, alfalfa producers would have access to lab tests similar to those that detect herbicide residuals.

Her research, still in the early stages, has revealed that seed variety, that of the crop in the field already and the variety that’s being replanted, does matter. It seems likely there are genetic factors involved.

“In fact, that may actually be a big piece of the variability that we see from field to field in autotoxicity in real life,” she said. “It’s not something we’ve ever selected for in alfalfa varieties before.”