As a new urban farmer, Cheyenne Sundance is intent on growing more than just fresh produce.

Sundance, who is mixed-race Black-identifying, saw a void in access to two things in her local farmer’s market – year-round fresh greens and diversity.

So she decided to fill them both.

Why it matters: Agriculture has not been a diverse sector, and there is interest in bringing more diversity into food production.

“I always say my farm is rooted in food justice because I do grow really great produce year-round but I also grow new farmers,” Sundance told attendees of the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario (EFAO) virtual annual conference in December.

In 2019 the 23-year-old launched Sundance Harvest, a small-scale garden business on one-third of an acre in North Toronto’s Downsview Park.

Using her two greenhouses and 10,000 square feet of outdoor plots, Sundance produces a steady flow of herbs, salad mix, kale, collards and chard year-round with more seasonal offerings throughout of tomatoes, mushrooms, sorrel, spinach, microgreens, zucchini, peppers cucumbers and cut flowers.

“These are very easy crops to grow in an intensive way,” she said, adding she grows year-round in the greenhouses, but starts production in the field in April and grows to the end of December.

“I find the most profitable thing for my urban farm is salad mix,” she said. “I sell easily 100 bags a week, 200 if I actually have the capacity to produce 200 bags.”

Sundance acknowledges if she farmed rurally it would cost less, likely involve greater land availability and easier infrastructure and crop expansion into items that require more space, such as squash and watermelon.

As an urban farmer, she said land is limited, costly and, because it’s rented, requires significant discussions before infrastructure expansion can take place if it’s even approved.

Read Also

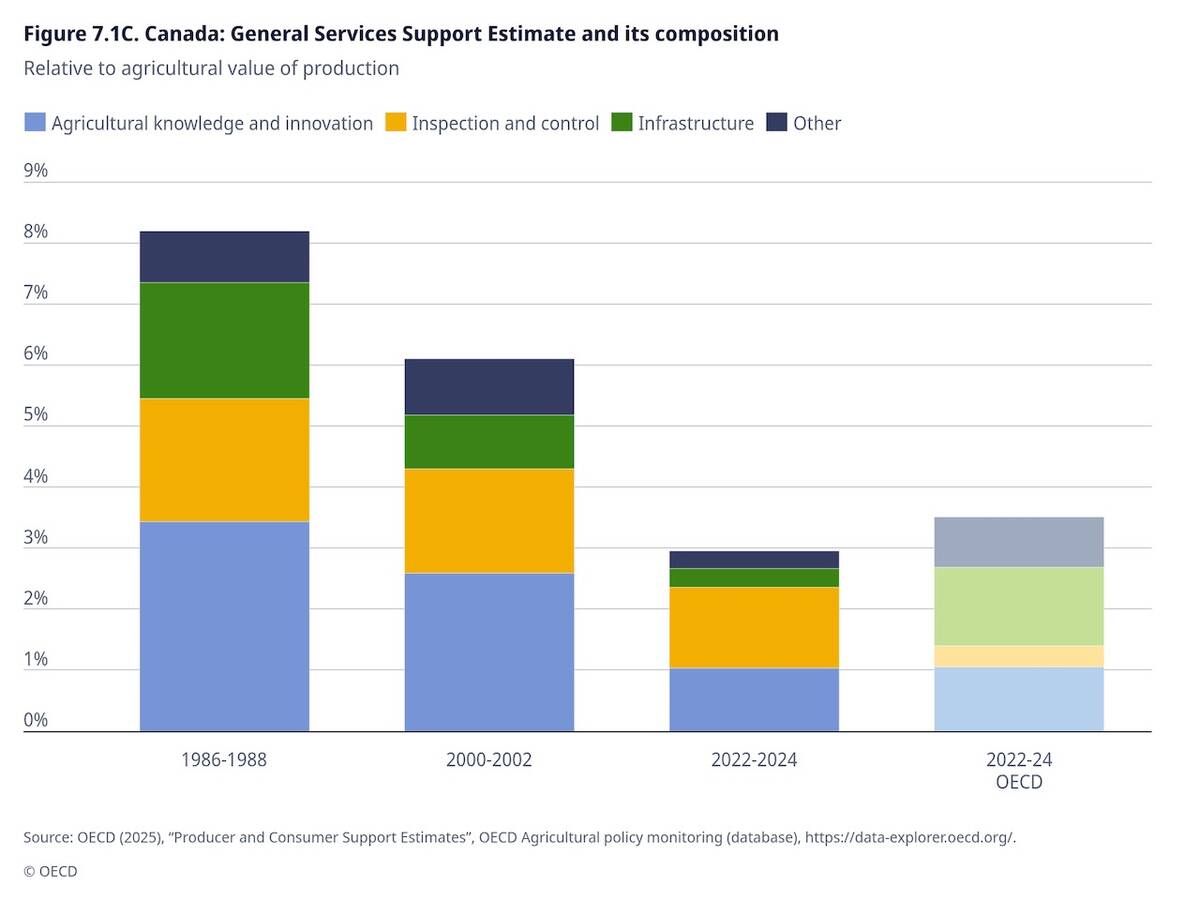

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

However, the greatest positive of urban farming is community engagement and being accessible to consumers by transit, which allows them to visit the farm, ask questions and engage with the process, said Sundance.

“For me, the upsides make it worth it,” she said, especially when it comes to establishing food justice and creating agriculture-based education opportunities for marginalized communities who often face higher rates of food insecurity, food injustice, social isolation and mental health crises.

A 2018 study from the University of Toronto’s PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research indicated the highest rates of food insecurity in Canada occur in Indigenous or Black households at 28.2 per cent and 28.9 per cent respectively.

Sundance, who grew up with food insecurities, wanted to provide a space where Black, Indigenous, Persons of Colour (BIPOC), LGBTQ2S, gender non-conforming and youth with disabilities could learn everything about agriculture from seed saving to harvesting, distribution to retail and gain control over their food systems.

Leading by example, Sundance assessed a void in her local farmers’ market, developed a business plan, applied for and received a $5,000 grant to launch Sundance Harvest and within a year has created enough steady income through her Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscription box and Dufferin Grove Farmers’ Market customers to provide herself with a salary and pay her staff a living wage.

“A lot of people in Toronto are very interested in urban agriculture and they want to support it in anyway possible,” she said. “I’ve only had one person drop out (of the CSA) and that was in the last few months because they moved.”

Her online farm store was part of the pandemic pivot many businesses made to stay afloat during the pandemic. Sundance’s online store includes unique maple products, wild-caught fish from Nunavut, herb salt, botanical tea and holistic snacks by BIPOC producers.

“Because there is such a lack of diversity in agriculture and a lack of opportunity for us I really wanted to centre our products in my store,” she said.

She tries to add a new producer to her site weekly.

Sundance Harvest has evolved so quickly she was able to launch Growing in the Margins, a free 12-week education program for low-income youth facing barriers within the food system.

It offered two streams, one in mentorship and the other a drop-in program, some of which has been suspended temporarily due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Sundance said the program is open to youth 18 to 25 who self-identify as low-income, BIPOC, LGBTQ2S, gender non-conforming or disabled who are interested in a career in agriculture or leading community food sovereignty movements, but lack hands-on farming education.

“I wanted to learn from someone who had a similar lived experience so they could mentor me, teach me and ensure that I wouldn’t have as much of a hard time getting started,” she said. “Growing in the Margins is the only place they (marginalized youth) feel safe to learn.”

Sundance said there is no labour exchange for their education. She provides a curriculum covering everything from seed saving to planting, irrigation to organic pest control and harvest to marketing to help smooth the path for others who have an interest in agriculture but no idea of how to start.

“The majority of the youth that finish the program actually start careers in agriculture,” she said.

Eventually, Sundance hopes Growing in the Margins will evolve into a closed-loop system where the community provides land resources for an urban farm. That farm feeds people and sells its produce at a farmers market creating financial support and jobs. The circle then begins again with potential urban farmers again being mentored and educated to the point they can start their own farms.

“I didn’t see myself represented in agriculture and I wanted to be a farmer,” she said. “It was really important to me… to have a farm that reflected something I didn’t see in agriculture.”

Each step she takes growing her business and Growing in the Margins brings her closer to her goal of eradicating systematic racism in the food system, shining a light on the profitability of urban farming and providing marginalized youth with an opportunity to see themselves reflected in the agricultural sector.