Labour vacancies cost Canadian farmers in 2018 nearly double what they cost four years earlier, according to research released recently by the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council.

Why it matters: More farmers are either not expanding or inefficiently operating their farms because of a lack of labour. That’s a problem for Canadian agricultural competitiveness.

The Labour Market Forecast found that 16,500 jobs went unfilled, costing $2.9 billion in lost revenue, or 4.7 per cent of product sales. Previous work pegged lost revenue at $1.5 billion.

Read Also

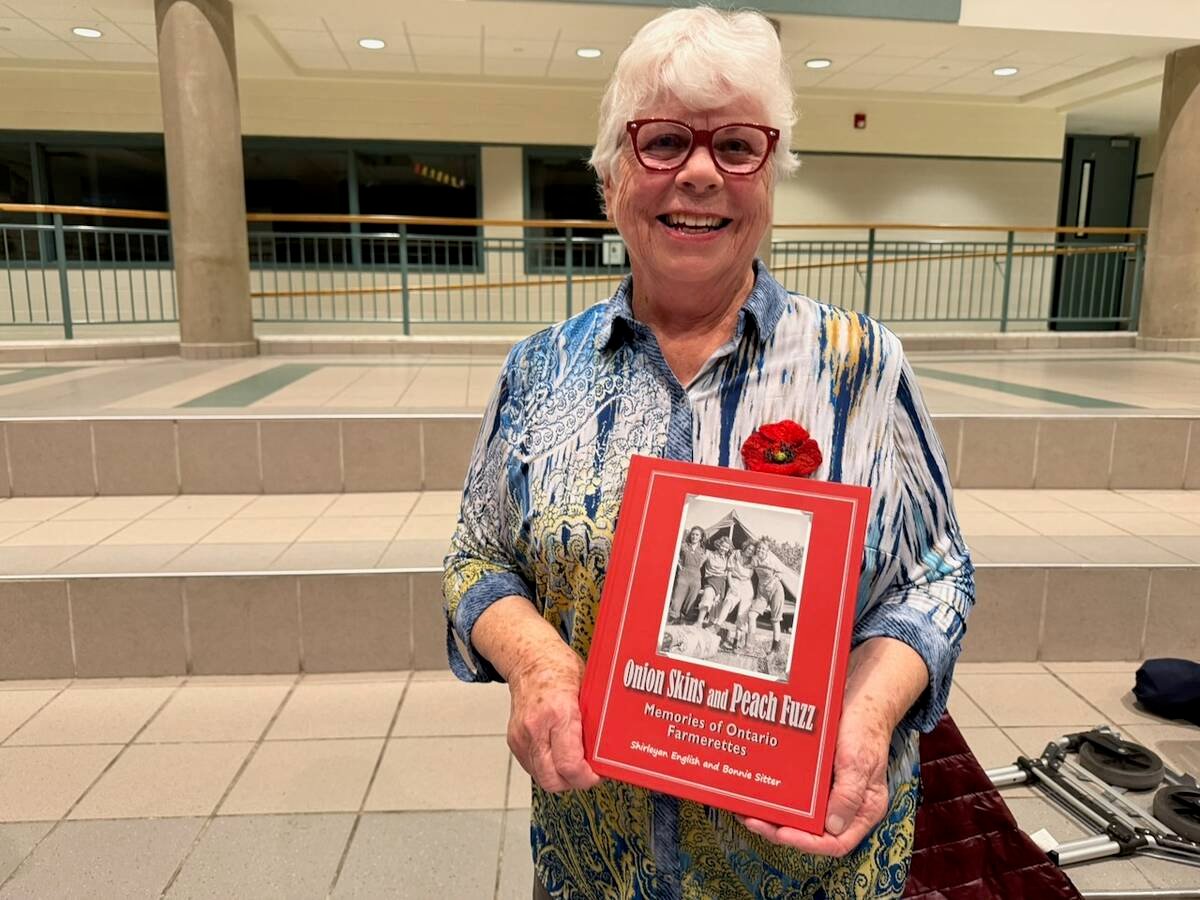

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

The bad news doesn’t end there.

The study forecast that labour requirements are expected to grow over the next dozen years. It projects a labour gap of 123,000 people by 2029. That will be about one-third of the entire labour demand for that year and it will be felt mostly in Ontario, followed by Nova Scotia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

“Among commodities, horticulture-based commodities will continue to experience significant labour gaps,” says the study’s executive summary. “However, grain and oilseed and beef producers will experience the largest increases in their labour gaps and account for much of the increase in the labour gap for the sector as a whole.”

Todd Crawford, an economist from the Conference Board of Canada, said Alberta faces the worst lost revenue, followed by Ontario, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

He noted that while lost revenue has risen, the number of job vacancies actually declined from 2014 to 16,500 from 26,400, thanks to technology.

He also said farmers have stopped posting all their open positions because they know they won’t find workers.

“Producers are telling us it’s costing us more and more every year,” Crawford said of the survey results. “Every worker we’re losing out on is now costing us more revenue, so even though we’re seeing the vacancies slide a little bit, the financial harm to the industry continues to increase.”

Debra Hauer, manager of CAHRC’s labour market information program, said the effect on grain and oilseed farms is significant due to the nature of the industry.

“Previously, when we had done this work in 2014 we knew that for every missing body in the grain and oilseed industry, that cost the industry $325,000,” she said. “Because the grain and oilseed industry has already gone quite far down that road of increasing innovation and technology, therefore for that industry each missing body has a disproportionately high effect.”

Crawford said each piece of equipment on a grain farm is capable of farming multiple acres, leading to high productivity. When a farm doesn’t have access to the workers, and that machine sits idle or isn’t used to potential, the cost is high.

In other sectors such as greenhouses and horticulture, the labour shortage is more acute but the productivity isn’t the same.

The domestic labour pool is expected to drop largely due to an older-than-average workforce and few young entrants.

Foreign workers now fill about 17 per cent of the agricultural jobs, but Crawford said that isn’t a long-term solution.

Other survey results found that 46 per cent of farmers who couldn’t find workers had to delay or cancel expansion plans and nearly 90 per cent said they experienced excessive stress because of labour issues.

The beef sector will be most affected by the aging workforce by 2029, with 40 per cent of its workers expected to retire. The grain and oilseed sector followed at about 38.5 per cent and then the sheep industry at 38 per cent.

The labour market forecast was conducted with 1,900 farm owners, employees and stakeholders across Canada in November and December 2018. CAHRC plans to release 22 reports that will include labour market forecasts for each province and major commodities in the coming weeks.