The province recently released its first soil strategy. The long document talks about much of what we know now about soil health.

It also talks about best management of soil health and highlights what some farmers are doing on their farms.

But it skirts around the major barrier to adoption. Many farmers have yet to find a way to make soil healthy practices, especially cover crops, pay consistently in an annual cropping system.

There’s little doubt that soil health is an issue in Ontario.

Read Also

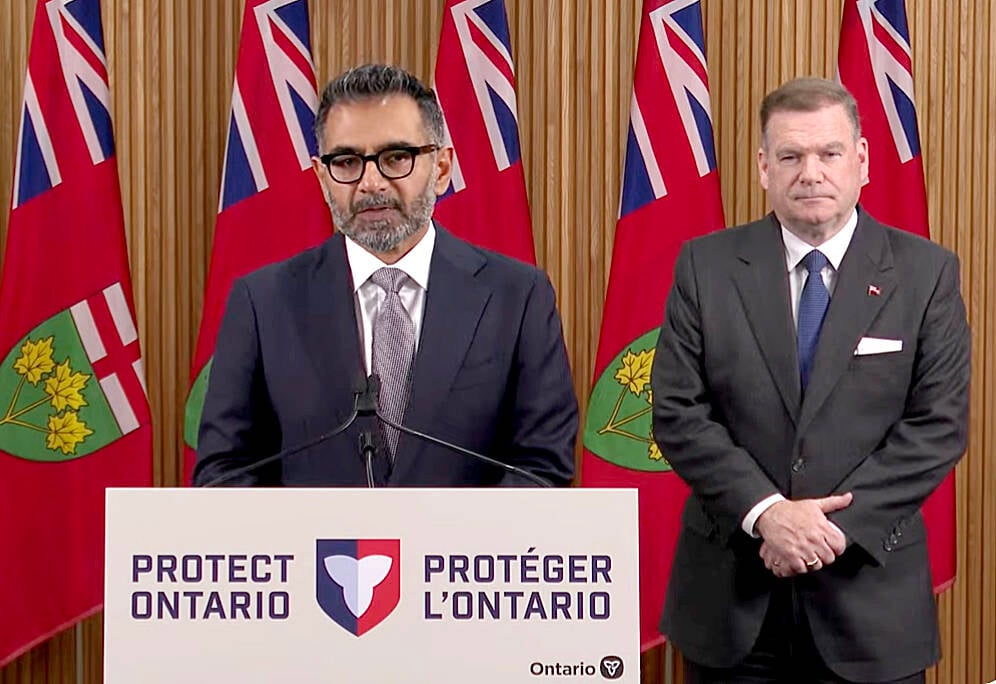

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

Some statistics from the soil strategy:

- 82 per cent of Ontario’s agricultural soils are estimated to be losing more CO2 to the atmosphere rather than increasing soil organic carbon.

- 68 per cent of Ontario’s farmland is estimated to be in an unsustainable erosion risk category.

- 53 per cent of Ontario’s cropland is estimated to have low or very low soil cover, covered less than 275 days or 75 per cent of the year.

- Tillage increased between the 2011 and 2016 agriculture censuses.

Some farmers have started using cover crops, as hay and pasture are plowed down to make way for greater annual crops in the province. From 2011 to 2016 cover crop use doubled from 12 per cent to 25 per cent. A lot of farmers have experimented with cover crops, but the range of cover crop mixes tried is extraordinary and there aren’t enough best management recommendations. The chance of making the wrong choice is high and then many farmers don’t go back to cover crops after a failure. I’ve seen that happen in my neighbourhood.

Increasing cover crop use is challenging. To get from 25 per cent to 45 per cent of farmers using cover crops would require another 10,000 farmers adopting the practice, according to the soil strategy.

The problem is a lack of easily identifiable economic benefits in an annual cropping system. Think back to the significant adoption of no-till planting during what can be thought of as the first wave of soil health concern, mostly centred around erosion, in the 1980s and 1990s. Yes, no-till helped improve soil health, but it has also made financial sense for many reasons — reduced fuel use, less need for equipment and lower labour costs.

The immediate benefits of cover crops aren’t as obvious on the financial spreadsheet.

An Iowa State study released in February showed that there was no financial benefit for Iowa farmers not using the cover crops for forage or grazing. This study has been used by those in Ontario with concerns about the economics of cover crops.

But there are a couple of issues with applying the results to Ontario. The study looked at cover crops in corn and soybeans systems. We have more balanced rotations in Ontario growing corn, soybeans and wheat. It’s much easier to get a cover crop up and going after wheat harvest, compared to soybeans and corn where cover crop establishment is more challenging and has less obvious benefit. A clover cover crop broadcast onto the wheat in the spring can create a nice nitrogen credit for the following corn crop — if the clover survives. The clover cover crop choice has made sense because there’s an easily-seen direct benefit.

The financial value of other cover crops after wheat or planted into growing corn or soybeans is more nebulous. Some years it’s there. Others it’s not.

The Iowa study also didn’t look at the economics of cover crops over a long term, and there is a lack of significant data to tell us how farms perform financially over a long term with cover crops.

We need those answers.

Farmers finance equipment, field tile, barns and shops, and of course, land, over long periods of time. Cover crops are an investment in soil infrastructure and so while the labour, equipment, seed and fertilizer used in cover crops show up as expenses in annual spending, they really need to be seen more like capital investments.

I doubt any accountant can make that magically happen, but there’s a need to find an economic driver for cover crops. Thinking of them as building blocks for soil infrastructure to support crops years into the future is a start.