The agriculture industry is rallying around farmers as drought conditions threaten crop outputs and livestock holdings.

To help farmers navigate the financial and mental toll the dry weather is taking on operations, both the Beef Farmers of Ontario and the Grain Farmers of Ontario hosted information webinars to offer tips and advice.

Why it matters: Farmers are facing significant losses in production yields due to drought conditions.

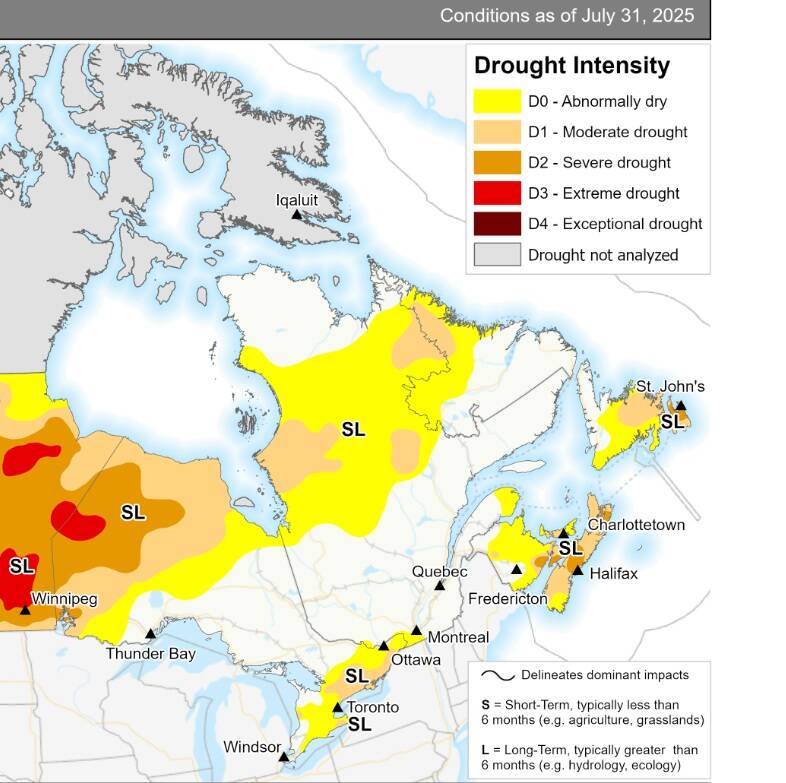

According to the latest market news from Syngenta, 34 per cent of agricultural lands in the Central Region of Canada, including Ontario and Quebec, were impacted by drought in July, up from 20 per cent in June and one per cent in May. Additionally, reports show that southern portions of Ontario and Quebec received less than 85 per cent of normal precipitation, with eastern Ontario receiving below 40 per cent of normal monthly precipitation.

Read Also

Footflats Farm recognized with Ontario Sheep Farmers’ DLF Pasture Award

Gayla Bonham-Carter and Scott Bade, of Footflats Farm, win the Ontario Sheep Farmers’ 2025 DLF Ontario Pasture Award for their pasture management and strategies to maximize production per acre.

“The reach of this drought is broadening its effect. And I know this firsthand. I live in the Trenton area, which is in the heart of Middle Eastern Ontario, and it has been affected not only by a very significant wet spring, but the impacts to our CRO, our crops, have been amplified as this drought takes hold,” said Jeff Harrison, GFO chair, in a webinar.

Crop insurance

One of the greatest challenges farmers are facing as drought conditions continue is navigating insurance claims. In regions like Saskatchewan, the federal government has offered drought relief assistance. In Ontario, however, the picture is not as clear.

Debbie Brander, manager of product management and industry relations at Agricorp, noted that the focus in the wake of drought conditions is production insurance, which covers yield losses due to dry conditions. She said this includes covering extreme yield losses in addition to lost income and higher expenses such as trucking water or moving livestock.

“A number of farmers across the province have coverage for their grain and oilseed crops. Crop losses due to the dry conditions that you’re facing are absolutely covered under this program,” she said.

“If your actual yield this year is below your guaranteed production, you’ll be paid a claim for the difference. A key feature of production insurance coverage is the flexibility to accommodate crops harvested for different end uses, like grazing or chopping as green feed. This feature is available regardless of the quality of your crop.”

She added that a process is in place to establish a yield based on the crop in the field, taking into account any damage caused by uninsured peril or dry conditions. In this case, she said, if the crop has minimal value, it will be assigned a nominal value.

Crop management

Experts are advising farmers to proceed with caution before writing off any crops or eliminating livestock in an effort to reduce costs. These moves could end up being more costly than anticipated if not planned out properly. This caution should also be applied to the use of pest control during this stage in the growing season, according to Horst Bohner, soybean specialist with OMAFA.

Based on existing trials, he said that experts can’t offer a specific number, pointing to a study in Manitoba where soybeans received approximately 10 extra inches of rain in July and August, and then they just left the beans alone.

“The interesting part is, not every year really impacted yield by as much as you might expect. But no question, 16 to 32 per cent on average yield reduction. So really, the message I have for you is to consider looking carefully, scouting carefully, to see if you have insects or, more likely, spider mites; those are still worth controlling,” he said.“As we get into thinking about winter wheat in some of those fields where there are extra weeds now and try to even out the harvest timeliness, pre-harvest desiccant is worth thinking about as well. There is no easy answer, as I think we all know, on the soybean front.”

Corn specialist Ben Rosser echoed this sentiment, noting that in these current conditions, four days of stress is enough to impact a corn crop.

“One other question that comes up quite often in dry areas is when you go out to your field and you see those lower leaves fired up; quite often it’s nitrogen deficiency. So the question is, can we go out and try to collect that issue in season if there’s still enough grain fill left? And in a lot of these cases, it doesn’t necessarily mean the nitrogen supply in the field is limiting. We’ve just had so little moisture, and nitrogen really relies on mass flow movement with water getting to the plants, so we just haven’t been able to get the nitrogen in that field to those plants,” he said.

In lieu of that nitrogen from the soil, he added that the plants are remobilizing nitrogen from those lower leaves to keep the upper leaves alive and help with things like grain fill.

“Practically speaking, especially if there’s no moisture in the forecast, it’s pretty tough to get any more nitrogen in those plants. If you are seeing that firing up, it doesn’t mean there’s none in the environment; it just means that those plants aren’t getting that nitrogen when they need it,” Rosser said.

He added that in extreme cases, this may not be an option for all farmers, suggesting that if the grain yield potential is not looking good, silage harvest could be an option to try to salvage that field.

“If you are going that route, I think there’s a lot of management that’s going to be required.”

Rosser suggests sampling the field and getting an idea of what moisture levels are like, noting that in consultation with an agronomist in central Ontario where crops are at this stage, moisture readings were still coming back above expectations.

“Despite the fact that plants look so dead and brown, the moisture can still be higher than what you think it is because of all the moisture in the stem, and in their case, they were still too high to be able to store and ferment that safely,” he said.

“Preparing for harvest in fields where moisture stress has been severe, it’s just important to prepare for more variability.”

Salvaging grain crops

Many farmers may be faced with trying to salvage grain crops to feed ruminant livestock. Christine O’Reilly, a foraging grazing specialist with OMAFA, believes there are more options than just salvaging the crop.

“Salvaging a grain crop is one option. It’s not all of your options. I’m going to be a bit cheeky and say that maybe your first step is actually checking the labels of the crop protection products that have been applied, because there are a lot of things out there that might prohibit actually feeding that crop to livestock.”

She said that information can be found on the Ontario Crop Protection Hub and the Health Canada website.

“Sometimes it’s not the active ingredient in a product that can be a problem for livestock. Sometimes it’s an ag event and emulsifier, something else that’s in that formulation that can be a health challenge. So make sure that you’re typing in the product name that you used to get the right results so that you can actually check on all of those potential limitations. Once you’ve done that, check if the crops are insured, then you call Agricorp to work through their process to have the use changed,” she said, adding that grazing and corn silage are viable options and that producers should be checking moisture levels.

“If it is slightly on the dry side, try to aim to feed that out during January and February, when it’s coldest, to help reduce heating when that silo is open, because dry silage is definitely a fire hazard, and some of those silos can go weeks or even months, smouldering away before anyone notices,” she said.

“They’re a really, potentially really dangerous situation with extremely dry silage. So a moisture test before chopping is really important if you decide, or your neighbour decides, to graze it. Strip grazing is great for both rationing out the feed so that it’s not wasted and helping avoid rumen acidosis, making cows or sheep really sick. Ideally, it’s a minimum of one day’s worth of forage at a time and a maximum of three days, because that keeps what they’re eating a little bit more consistent and helps minimize that.”

She said farmers may also want to consider raising the cut height higher to manage nitrates, which she said accumulate in the bottom of a plant.

If a rain event does occur, she suggests waiting to harvest or graze due to high levels of nitrates in corn and cereals.

“Ideally, at least a week before harvesting or grazing, that gives the plants a chance to turn all of those nitrates into protein, so it brings that danger level down,” she said. “Get a nitrate test before allowing livestock to eat those crops, because there’s a lot of high-nitrate feed out there, and we don’t want to have a wreck. Work with a nutritionist to dilute those forages to safe levels, and really be aware of the increased risk of silo gas coming off of those.”

Livestock management

With crop yields threatened, farmers are looking at alternative ways to manage livestock. Chad Madder, a beef cattle specialist with OMAFA notes that there are options available that can help minimize financial losses.

“The obvious challenge that a bunch of us are facing in these dry conditions is maintaining feed supply for our livestock, whether that’s pasture or harvested feed, and the solution to any supply challenge is to either increase the supply or decrease the demand,” he said.

“In terms of increasing supply, unfortunately we can’t make it rain. So if your pastures are depleted to the point where they’re not keeping up, your obvious option is to try and supplement with some hay or other forage. In terms of those hay reserves, they may be depleted or becoming depleted, either because your yields were poor or because you’re now having to feed hay in a time of year that you’re certainly not planning to.”

One option to reduce feed demand is to reduce the number of livestock. This includes marketing any cull animals as early as possible and selling yearlings, calves, and lambs earlier than initially planned.

“I would sort of caution people to look at the cost benefit of selling animals early versus what it would cost you to purchase feed and stick to your sort of original marketing plan,” he said, adding that farmers want to avoid depleting a herder flock.

“If somebody were to consider getting rid of 10 otherwise productive cows just in an effort to conserve hay and then go and replace those 10 cows with heifers next spring, I think it’s a pretty reasonable estimate, maybe even a little bit low, that that could cost you $50,000, and look at how much hay you could buy for that $50,000. I suspect in most cases that math is going to say, if you can buy hay, you should buy hay.”

Madder suggests, if already feeding hay, to consider creep feeding as a way to reduce the demand on pasture, which can also enhance your calf or lamb performance. Early weaning can also mitigate losses and reduce physical demand on heifers.

“It also makes it a little bit easier to supplement those growing animals directly if you’ve got them weaned somewhere, whether that’s moving them to better pasture, if you have some better quality forage, or supplementing with grain,” he said.

“Early weaning does provide the option to modify your marketing plans if that’s the route best for you. But I also encourage people to consider supplementing with grain more as an issue for growing animals, probably more than putting grain in for your cow herd or your sheep flock. This will reduce the strain on the pasture and also has little impact on performance, as those growing animals that may not do as well on medium-quality hay can still maintain pretty good performance, comparable to good pasture.”

Madder adds that any changes to feeding should be done in consultation with a nutritionist to avoid unintended consequences.

Land management

Keeping pastures lush and nutritional can be difficult during drought periods. This year’s drought has left many pastures lacking vital nutrients for animals.

O’Reilly cautions that it is important to scout perennial forage crops for insect pests during dry weather. She adds that rotational grazing can help maintain the health of forage crops.

For cattle livestock, this can be achieved by combining different groups into one group so that only one pad is being grazed at a time, giving a longer rest period on used pads.

“It helps both the plants recover faster and also helps reduce evaporation from the soil, something that producers in the Prairies do regularly because they’re often more limited than we are [in Ontario],” she said, adding that livestock owners should also ensure they are allowing enough rest time in paddocks to give grass enough time to grow back.

Ongoing monitoring

With drought conditions expected to continue well into August, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness told Farmtario it is continuing to monitor crop conditions to ensure that resources are put in place to help farms cope.

“We understand that the recent dry and hot weather is affecting farms across Ontario, particularly in central regions of Kawartha Lakes, Durham, Peterborough, Northumberland, Prince Edward County, Hastings, and Lennox and Addington. It is too early to say how the dry weather will impact overall yields, as they naturally vary from year to year due to changing weather patterns,” said Connie Osborne, senior issues coordinator with the communications branch of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness and Ontario Public Service.

She said ministry specialists are actively monitoring crop conditions and water access for livestock, sharing timely information with farmers and agri-food businesses. She added they are also offering guidance on best practices to help manage crops and livestock effectively during challenging weather.

“We recognize the stress this creates for farmers and want them to know support is available. Ontario offers a range of business risk management programs to help farmers manage unexpected events like extreme weather,” she said, adding that farmers can also contact the Agricultural Information Contact Centre at 1-877-424-1300 for information about ministry programs and connect callers with mental health professionals in their communities.