The pursuit of efficiency in business has not produced the results that most people are looking for, says business professor and author Roger Martin.

Martin, a professor emeritus at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, says that in complex systems like economies, not every direction has a healthy outcome and systems should continue to evolve.

“For one reason or another, the world falls prey to models that feel logical in some narrow sense, but in a broader more holistic sense, are just bad models.”

Read Also

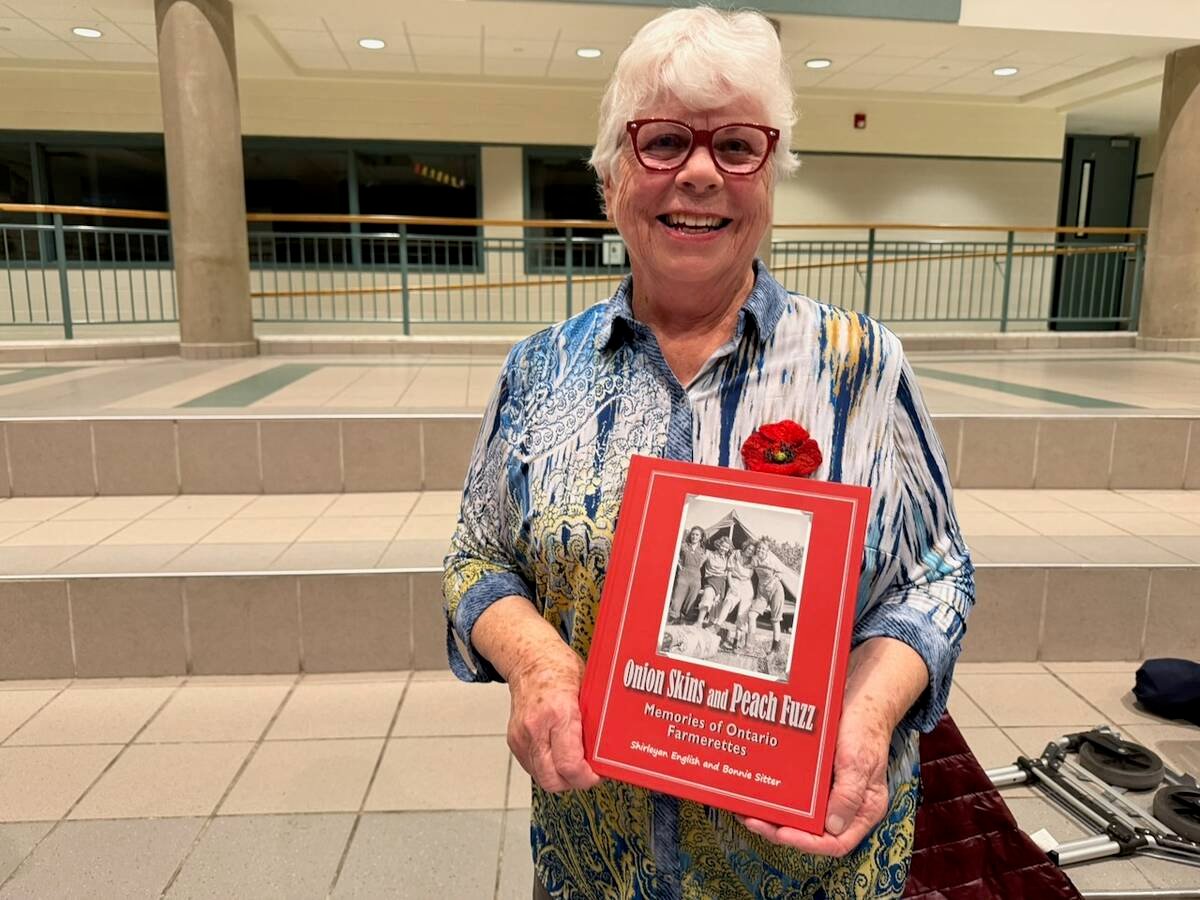

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

In the current economy, that’s led to a narrow band of people who have become extraordinarily rich, and most of the rest of the population stuck at the lower end of income. Martin says the pursuit of efficiency is one of the bad models that contributed to that result.

Why it matters: Economic systems fall into traditions of doing things the way they have always been done, despite potentially harmful outcomes, including in agriculture.

Humans tend to simplify systems and the results are the creation of proxies that are taken to represent larger results, even when they aren’t connected.

For example, Martin, who recently spoke to the Midwest Cover Crops Council annual meeting hosted by the University of Guelph, says the drive to lower wage rates is one commonly used proxy for business success.

That might work in the short term. In the long term, businesses with lower wages might think they’re more efficient because their labour costs are down, but “then customers stop showing up because it is a miserable place to shop because customers can’t find anything.”

Costco, for example, makes sure to pay its workers well, with the belief that they will be more dedicated employees and better able to help customers – which drives increased business.

Systems as large as economies should be thought of as jungles instead of machines, says Martin, whose book When More is Not Better: Overcoming America’s Obsession with Economic Efficiency, was the basis of the discussion.

A machine such as a car can be fixed by people with different skills. Then those pieces, whether they be the drive train or the entertainment system, can be optimized and put back together and the sum is a functioning car.

But in the jungle big trees grow and smaller trees behind them independently grow at an angle to get some sunlight. They are flexible and adaptive.

That’s the reason why just pulling a lever won’t fix the economy. Martin says government legislation needs the ability to be tweaked because no one can predict its effects before implementation.

“The minute you do something, people adapt to it,” he said during the keynote conversation funded by the Future Thinkers Fund created by the 1959 class of the Ontario Agricultural College. He was interviewed by Mel Luymes of Headlands Ag-Enviro.

An example is the Science Research Tax Credit program, which aimed to spend $300 million to encourage research at the company level.

“What happened is that people developed all sorts of schemes for trading these things. They shut down the program after it got to $3 billion. Almost all of it was trading paper among companies,” said Martin.

Striving for correct answers is futile because an answer that is right today will be superseded by a better answer, says Martin. Some people see that as a pessimistic outlook on the world, but Martin says it gives him incredible optimism about the future because humans continue to learn and then build upon that knowledge.

For example, some people might see saving the soil and saving the farm as incompatible. However, there will be common areas between the two that can create success for both goals of saving the farm and saving the soil.

“Bad models need to be replaced by superior models, not right models, superior models.”

Agriculture applications

A panel from the agriculture and food sector discussed Martin’s ideas in relation to farming.

A focus on bushels per acre is one proxy that is followed by many in agriculture, said Dan Petker a Port Rowan farmer.

If productive capacity of the land is lost, then there can be a long-term loss in bushels of crop produced, he said, using the example of a farm he lost as a rental because someone was willing to pay more. The new renter doesn’t use Petker’s tillage and cover crop practices and he says the land is washing away more than it did.

Alfons Weersink, a University of Guelph professor, said that he was struck by how Martin’s concept that slack in an economic system can mean greater resilience applies to the food system during COVID-19. Farms, processors and distribution systems were specialized, often to supply either the retail or the hospitality sector. When the hospitality sector closed last March, there was a large amount of work for some in the system to pivot to supplying retail.

“There was no give in the system,” he said.

Crystal Mackay, founder and CEO of Loft32, said efficiency isn’t important when trust is lost, such as in Manitoba where it was expected the hog sector would grow and be more efficient, but a 10-year moratorium on new hog barn building was created that threw sector efficiency expectations out the window.

There was also discussion of Martin’s suggestion that if traditional paradigms aren’t working, it’s OK to come up with a new solution.

Reliance on commodity crops in an example of farmers being pushed in one direction and having to rely on global price-setting mechanisms.

“We’re being asked to put values on our value system, but we’re being paid in commodity prices,” says Mackay.

COVID-19 has driven the need to look to new solutions.

Cher Mereweather, CEO of the Provision Coalition Inc. that provides sustainability solutions to food companies, said that many local food companies had their best year ever as consumers looked to products closer to home.

“People are coming out of the woodwork and people want to support that. It’s going to drive changes when the consumer spends with dollars and cents,” she said.