Technology has always been a driving force behind productivity growth in Canadian agriculture, and the trends of mechanization and increasing farm scale have typically been associated with a need for fewer people.

The threshing crews making the rounds a century ago harvesting the annual crop were replaced by tractors and threshing machines. Herbicides reduced the amount of tillage farmers need to control weeds, and new genetics helped boost yields to ever-rising new heights. The companies producing those crop inputs have consolidated, as has the number of farms — which has had the effect of reducing the number of jobs in the sector over time.

Read Also

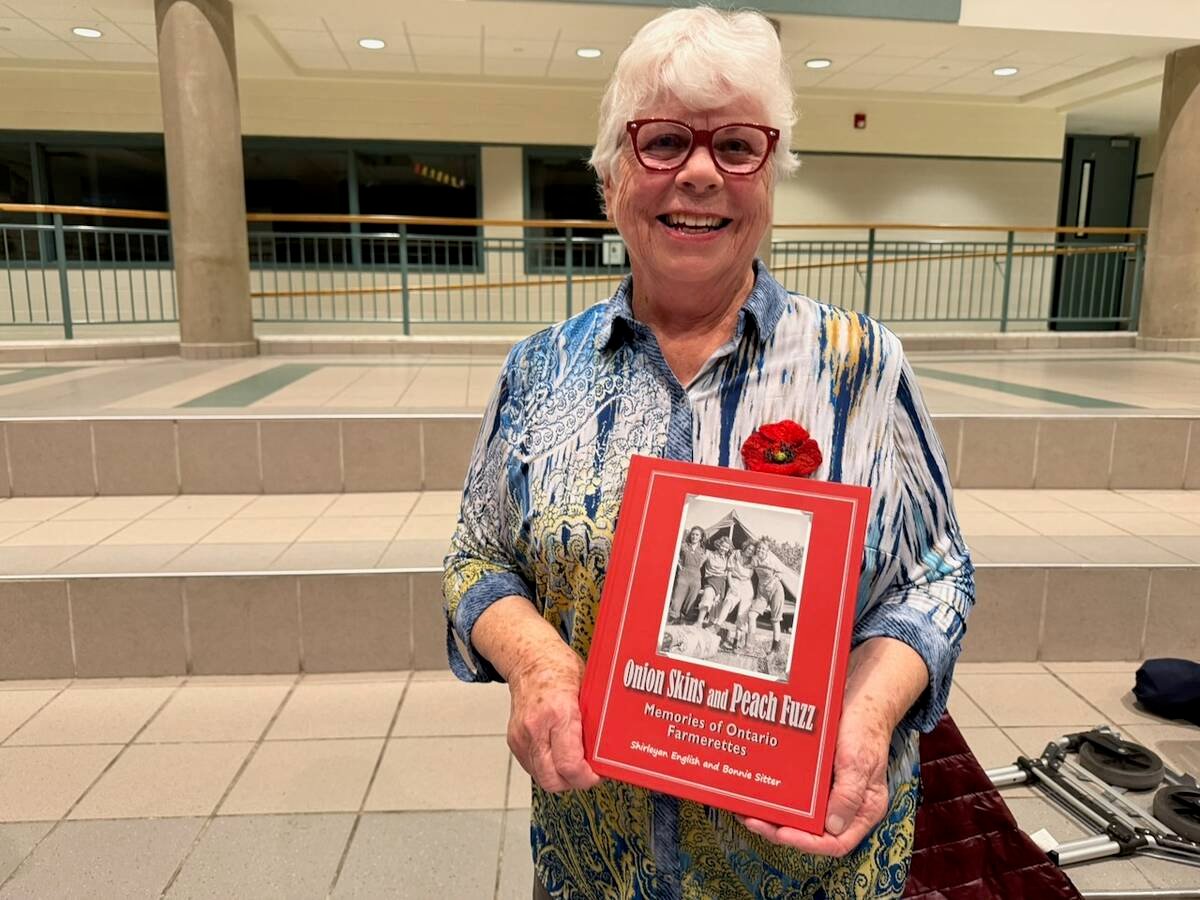

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

In a report called “Farmer 4.0: how the coming skills revolution can transform agriculture,” researchers with RBC say that the sector has shed 31 per cent of its jobs over the past 20 years due to mechanization and consolidation.

At the same time it has led the nation in productivity growth at annual rates of 5.5 per cent.

But it has become apparent over the past decade that the sector has now hit a labour force wall and it’s one that could cripple its future growth. Productivity growth has slowed to a crawl, Canada’s share of the global agricultural exports is declining, and investment in new technology is lagging.

The lion’s share of those declines is tied to a lack of people to do the work, although access to investment capital is also an issue.

The Canadian Agricultural Human Resources Council says there are currently 16,500 jobs that can’t be filled even with the addition of 60,000 temporary foreign workers. That number will grow to 123,000 jobs over the next decade.

“The story isn’t that we’ll need less, it’s that we’ll need more,” said Andrew Schrumm, RBC’s lead researcher.

Despite its relative wealth and resources, Canada is gradually losing out to parts of the world where there is no shortage of people and better access to investment to do the work.

The RBC found that investment in agricultural technology in Canada has fallen behind that of its major competitors as well as some of the emerging economies, including India and Brazil. Even though Canada’s volume of global exports has grown, its share of the global market has fallen because others are growing faster.

Canada’s share of global exports fell from 6.3 per cent in 2000 to 4.9 per cent in 2005 to 3.9 per cent today, despite increased output, the report says.

Agriculture needs more workers generally, and it will need workers with widely divergent skills pulling from five categories, the deciders, enablers, specialists, advisers and doers.

The “doer” category representing farm labourers is the category showing the most acute shortages over the short term, but it is also the category that has the greatest potential to see jobs displaced by automation. The other categories, which would encompass workers in the service industry, such as mechanics, or crop management specialists, or financial advisors are set to experience robust growth in demand.

The report said the current labour shortages would escalate over the next decade as the current operators aged 55 reach retirement. “Attracting youth to careers across food production is critical,” it says.

The same goes for attracting women, new Canadians and Indigenous people, the report says. “Big barriers remain, including awareness, access to capital and land, as well as the physical nature and remoteness of the work.”

It notes only 1.9 per cent of farm operators are Indigenous, despite the nearly nine million acres of territorial land they might access.

The capital-intensive nature of agriculture is a huge barrier for those potential sources of human capital.. The RBC report categorizes farmers’ access to investment capital in Canada as “surprisingly low” with Canadian agriculture occupying a 1.9 per cent share of national commercial lending. The global average is 2.9 per cent and in New Zealand, it’s 14.1 per cent.

This report calls for a major investments in interdisciplinary skills training, new technologies and improving the resources for investment in order to keep up with the competition and help the sector reach its full potential.

“No other country has as much land, water or market access — or the education system to develop farmers and food producers who can thrive in a hyper-connected, data-driven economy, “ it says.

“It’s more than an economic imperative. Our food security is at stake, as is our chance to feed the world in more sustainable ways.”

Laura Rance is vice-president of content for Glacier FarmMedia. She can be reached at [email protected]