Federal, provincial and territorial government collaboration is vital to the future of Canada’s agriculture sector, said panelists at a May 31 webinar.

Organized by the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute, the webinar focused on a report by University of Toronto professor Grace Skogstad entitled Towards a Collaborative Sustainable Agriculture Strategy for Canada.

Why it matters: Collaboration between different levels of government are key to Canada’s agricultural sustainability.

Read Also

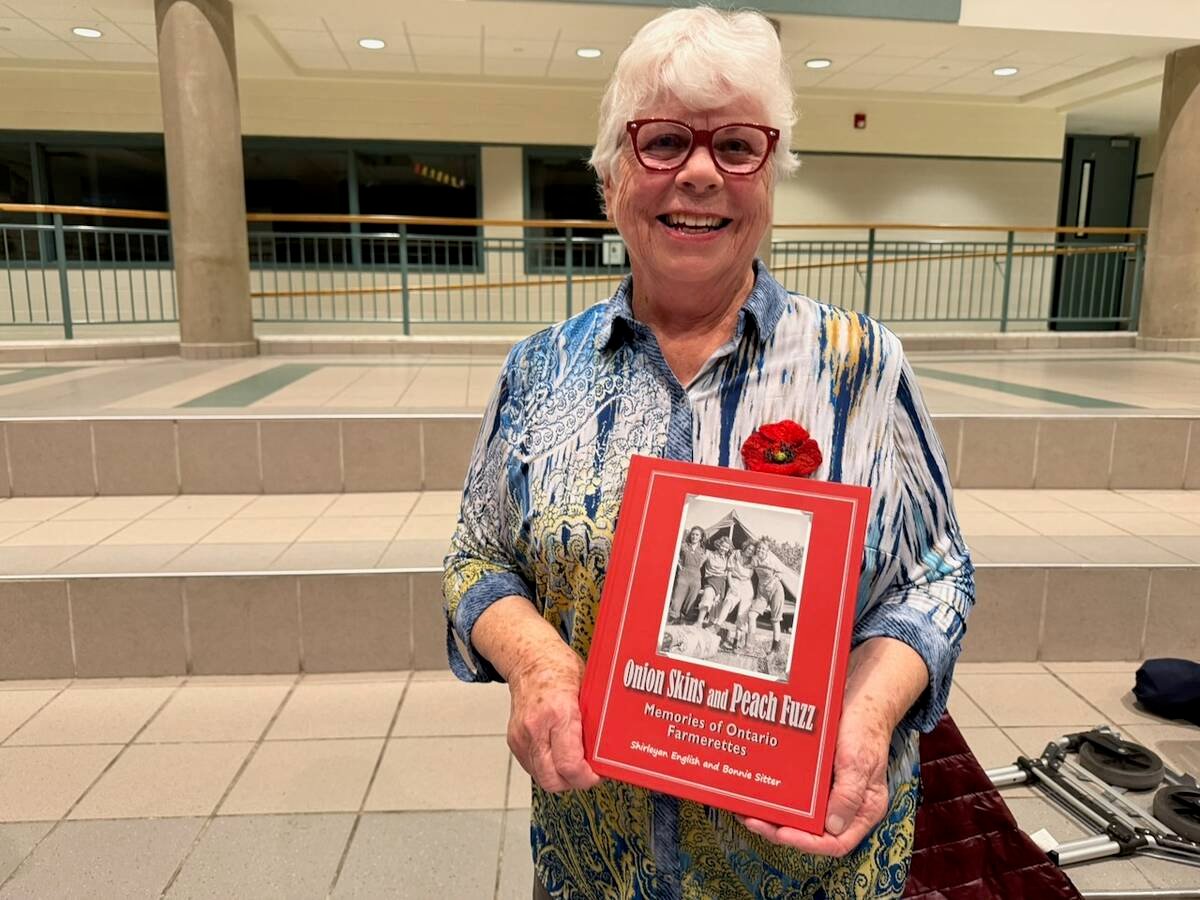

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

Skogstad opened the webinar by discussing the challenges collaboration between the federal, provincial and territorial governments, noting differing regional priorities often create tension.

“FPT governments often have incentives for independent action and those arise not just because they’re able to act independently, but also because they have different policy and political priorities.”

Skogstad said provincial governments are often responsible for meeting targets set by the federal government.

“The case is that the government of Canada can set such mandatory national targets and performance standards, but it would be largely reliant on provincial and territorial governments to implement them and enforce them. So, the question then is how to get all the governments on board to do this.”

Panelist Keith Currie, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, used the federal government’s Carbon Pricing Backstop program as an example of FPT collaboration on climate issues, because it represents an “overarching program that puts a price on carbon, but allows the flexibility of provinces and territories to design their own plan.

“If it’s nationwide, you’re never going to get consensus,” said Currie. “We’re too vast, we’re too different, but from a regional aspect, those differences will be pointed out.”

Skogstad agreed that regional differences make universal agreement difficult.

“If all you’re doing is insisting everybody agree on everything, then you really do get lowest common denominators, I’m sure.”

Currie said provincial politics can stymie collaboration, citing recently re-elected Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and her promises to fight the Trudeau government as a recent example.

He said agriculture ministers can help surmount barriers in agricultural policy.

“There’s the political side that we have to figure out how to get past and I think that’s where we can use the agriculture ministers to buffer that,” Currie said.

“Maybe you can use the ag ministers to bridge those bigger, inter-provincial and federal and territorial government gaps.”

Currie said provinces often bear the fiscal brunt of climate legislation.

“I don’t think it’s fair to ask the agriculture minister to pony up the necessary funds. Climate change is bigger than agriculture, you know? It’s infrastructure, it’s environment, it’s finance, natural resources, transportation.”

Panelist Harvey Sasaki, president of Agri-Saki Consulting and former employee with the B.C. agriculture ministry, noted the differences between B.C. and the Prairie provinces.

“Regional differences do exist. British Columbia is very different in terms of its agricultural landscape. When you compare it to the Prairies, we have much, much smaller farms, we’re more diverse,” said Sasaki.

This size difference has led to policy frustrations in the past.

“Wanting to provide crop insurance for 10-acre strawberry farms versus the, you know, thousands of acres of grain production on the Prairies, how do you find some grounds in terms of policies driven by risk management?”

Currie said financial differences between different sizes of farms should be considered in FPT collaboration.

“We do have a lot of smaller farm operations across this country,” he said. “Farmers will pony up, they just can’t do it all. But the larger farmers can cash-roll much better than the smaller farmers can. So there has to be that flexibility in the funding.

“Trying to put a one-size-fits-all plan in place just doesn’t work because of the vast differences in in the kinds of agriculture. Growing alfalfa in Alberta is different than growing alfalfa in Ontario or Quebec.”

Skogstad said she believes collaboration is possible. She gave examples, including farm income safety nets, dairy and poultry supply management, and the resolution of agricultural trade disputes under NAFTA and the World Trade Organization.

She said governments may “realize it’s been ideal and necessary for them to pool their fiscal and regulatory resources to accomplish a goal and overcome policy gaps.”

Skogstad gave examples of potential building blocks for collaboration:

- 60/40 federal/territorial/provincial cost-sharing

- Built-in provincial/territorial flexibility when it comes to certain programs

- Giving provinces and territories a role in setting standards and targets

- Increased incentives to collaborate If environmental performance standards are important to international competitiveness of Canadian products

Curry agreed with the cost-sharing concept.

“I think if we’re going to get to wherever we need to get … there either has to be an incredible amount of increase in investment by the feds, which would, again, require the provinces to pony up, because it’s a 60/40 per cent split between the feds and the provinces.

“That would mean that the provinces would have to come on board and you know, maybe it’s time we looked at it a little different.”

Skogstad has a positive outlook on the future of FPT collaborations.

“I’m really optimistic that the collaborative institutional norms that have been built up over decades in the agricultural sector will provide the foundation for governments to join and deploy their jurisdictional authority to tackle what I think most people see as the really existential crises of our times.”

The federal government recently released the Sustainable Agriculture Strategy, which aims to create a shared direction and vision for climate change resiliency in Canada.

“It’s a strategy that is being built by the country, by the players across this country. And what that’s going to do is allow the federal government to go back to the provinces and territories and say ‘we consulted from coast to coast to coast, and this is what we heard from the stakeholders,’” Currie said.

“That will then give them a little bit of leverage to go to the provinces to say ‘OK, your people said this, now how are we going to work together to drive this forward?’”