An innovative off-grid pasteurization tool for farmers in East Africa developed by University of Waterloo students is gaining international attention.

The university’s Safi just recently won a global food system challenge, as well as a digital innovation award through the the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) .

Why it matters: Farmers in Africa don’t have access to advanced pasteurization methods, which puts public health and their livelihoods at risk.

Unpasteurized milk is a major cause of illness and early death in East Africa, which has the highest global incidence of deaths in children under five from milk-borne diseases. Most milk in this region – including Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda – is distributed to consumers straight off the farm so conventional pasteurization isn’t an option.

Read Also

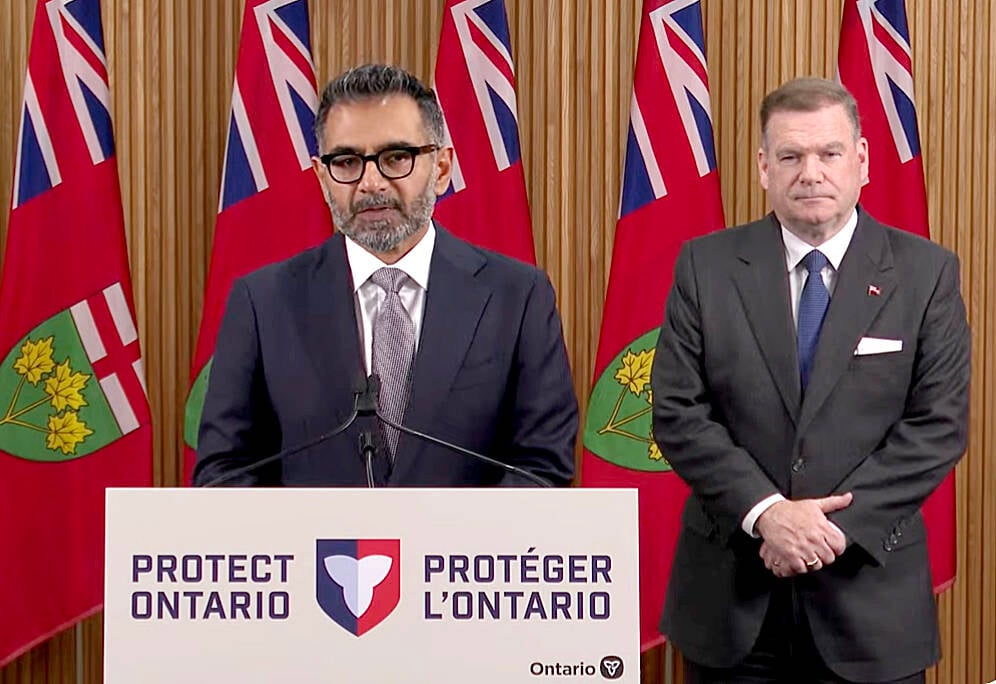

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

Safi co-founder Miraal Kabir, a graduate of a double degree program in computer science and business administration from UW and Wilfrid Laurier University, grew up in Oman, which the country struggled with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) corona virus spreading through raw camel milk during her childhood.

So when she stumbled across the problem of unsafe milk in East Africa during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, she felt driven to make a difference.

“We knew pasteurization would get rid of these pathogens, but about 90 per cent of milk sold in East Africa is sold raw and the supply chain is farmers distributing their milk through neighbourhoods,” says Kabir.

“So how can we make pasteurization accessible so that farmers can do it before they sell their milk?”

Conventional pasteurization systems are too expensive for most East African farmers to purchase, and even if they were to have such a unit, they largely don’t have access to grid electricity, so they’re unable to actually run it.

Working with fellow students, including co-founder Martin Turuta, led to the development of a simple pasteurization control unit that uses a high temperature, short time pasteurization method. Farmers can heat milk on their stoves and if they use the Safi device, its temperature probe will tell them when conditions for pasteurization are met, while still retaining the milk’s optimal nutrients.

The Safi team developed the first prototype in Canada – where Kabir says it took a year to secure the necessary government permits to access the raw milk they needed for product testing – and then took it farmers in Rwanda for on-the-ground testing in April 2023.

They’ve now been to Rwanda, Kenya and Uganda five times and are running pilot programs in the region. They’re returning at the end of June to distribute a further 125 devices, and by the end of the year, they’ll be distributing another 680 units to farmers in the region.

Each device is sold to a Non-Government Organization (NGO) for US$225, which farmers can purchase through a micro-loan program. Farmers receive a premium for selling pasteurized milk, which is captured through a “pay as you pasteurize” model to pay back the loan; Safi’s digital dashboard gives farmers the proof of pasteurization they need to capture those higher prices.

Last year, the team won the America Society of Mechanical Engineers Innovation Showcase, which got them an invitation to present at a United Nations forum.

Earlier this year, they won the Seeding The Future Global Food System Challenge run by the Institute of Food Technologists, which is helping to fund some of their current work. They also recently received a $100,000 grant from a fund in Kenya.

Key to their growth and success has also been the Velocity Fund at University of Waterloo, which supported them financially and also gave them much needed space to build and test their prototypes.

“This was a problem that resonated with us, that we could save lives and help farmers rise out of poverty,” Kabir says.

“Safi means safe in Swahili and we always say that our true vision is for people not to be afraid that milk is dangerous but confident that it is “safi”.

They’re now moving production of their devices to Rwanda and will be relocating to East Africa this fall.

“We’ve done a ton of work to formalize and standardize our device so that we can move into manufacturing at-scale,” adds co-founder Turuta.

Long-term, they’re looking to larger markets like India, which is home to most of the world’s small-holder dairy farmers.