Canadian hog producers would be wise to chew slowly as they digest a recent report suggesting United States pork products need a little more fat and a lot more marketing.

The paper — released by CoBank, one of the largest private agricultural lenders in the U.S. — focuses on that country’s pork production and consumption, but the North American hog and pork industries are highly integrated. Impacts from the report, if there are any, will spill north across the border.

Nearly a quarter of pigs born in Canada are sent to the U.S. for feeding and slaughter. Sixty per cent of those are weanlings sent to U.S. feeding operations. Canada also exported US$1.7 billion in pork products to the U.S. in 2024 and imported US$850-million worth back.

Read Also

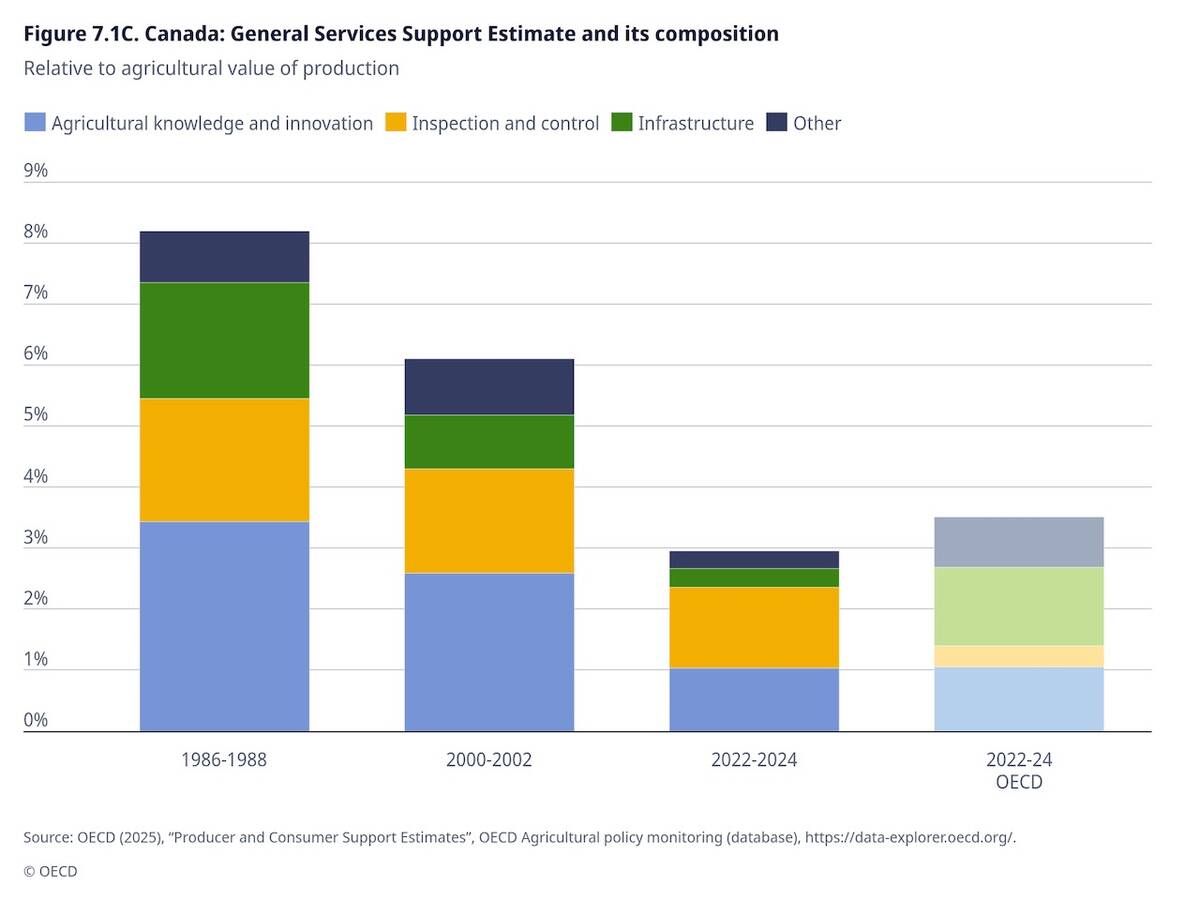

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

CoBank says the U.S. industry’s continued reliance on exports, accountable for nearly a quarter of its production, is becoming too risky, given “new trade policies” creating more volatility in global trade.

Even without President Donald Trump’s tariff wars in the mix, trade with China has fallen sharply since the record sales of 2020. Chinese domestic production rebounded faster than expected following an outbreak of African swine fever in 2018.

Bacon has achieved a cult-like following in the U.S. and sausage products have gained appeal, which has doubled market prices for the pork bellies and trimmings used to make them. However, “muscle cuts” such as pork loins and hams are often discounted. They aren’t as convenient and consumers don’t know how to cook them, according to the report.

Exports of so-called “variety meats” such as livers, hearts, kidneys, tongues, stomachs, snouts, ears, feet and tails were worth $1.3 billion in 2024, but they aren’t popular menu items in North America.

“Any trade barriers in place for countries that purchase variety meats could cause implications for the U.S. pork sector because those products have extremely limited demand in the U.S.,” CoBank says.

U.S. pork consumption has remained static at about 22 kilograms per capita since the 1970s. Increasing that will be challenging because the parts of the animal the industry currently exports are such a hard to sell to U.S. consumers.

“If the U.S. consumer is to reimagine pork, the pork industry may need to make drastic changes, including recalibrating the genetic hog makeup and showcasing different cuts at retail and through food service.”

Pork industries on both sides of the border have launched campaigns designed to convince consumers they need more pork on their forks. Canadian consumption is much lower than the U.S., about 16 kilograms per capita, but recent marketing efforts have achieved increases of nearly 15 per cent.

CoBank cites Kansas State University research, which names taste as the primary driver for protein purchases. When it comes to animal protein, the flavour is in the fat.

That’s a problem for a sector that heeded previous low-fat messaging and shifted genetic focus towards lean carcass weights, rapid growth and more efficient feed conversion.

CoBank is signalling a shift in market direction that has obvious implications for the Canadian sector, but it’s unclear how this might play out. Changing the genetic makeup of the hog to bring more fat into the equation needs to be considered carefully, given society’s love-hate relationship with fat.

Teaching consumers more tasty cooking practices combined with changes to how pork cuts are prepared and marketed might achieve the same outcome without compromising pork’s lean nutritional profile.