Most dairy operations have a footbath, whether built into concrete or set up as a portable tub near the parlour exit. The practice is common, but the results are not always consistent.

On some farms, footbaths help control infectious hoof diseases effectively across the herd. On others, they offer little benefit, no matter what solution is used. The difference often lies not in the presence of a footbath, but in how it is designed, maintained, and integrated into the broader hoof health program.

What makes a footbath truly effective rather than just a routine fixture?

Read Also

Maizex brings Elite forage seeds under its brand umbrella

The seed catalogue for Maizex Seeds takes on a different look for its 2026 edition thanks to the introduction of a new marketing initiative dubbed “Ration 365.”

Digital dermatitis (DD) is now recognized as the most common infectious hoof disease in dairy cattle. Once established in a herd, it spreads rapidly. This is where the footbath plays a critical role not as a standalone solution, but as a herd-level tool to reduce reinfection pressure and prevent new lesions.

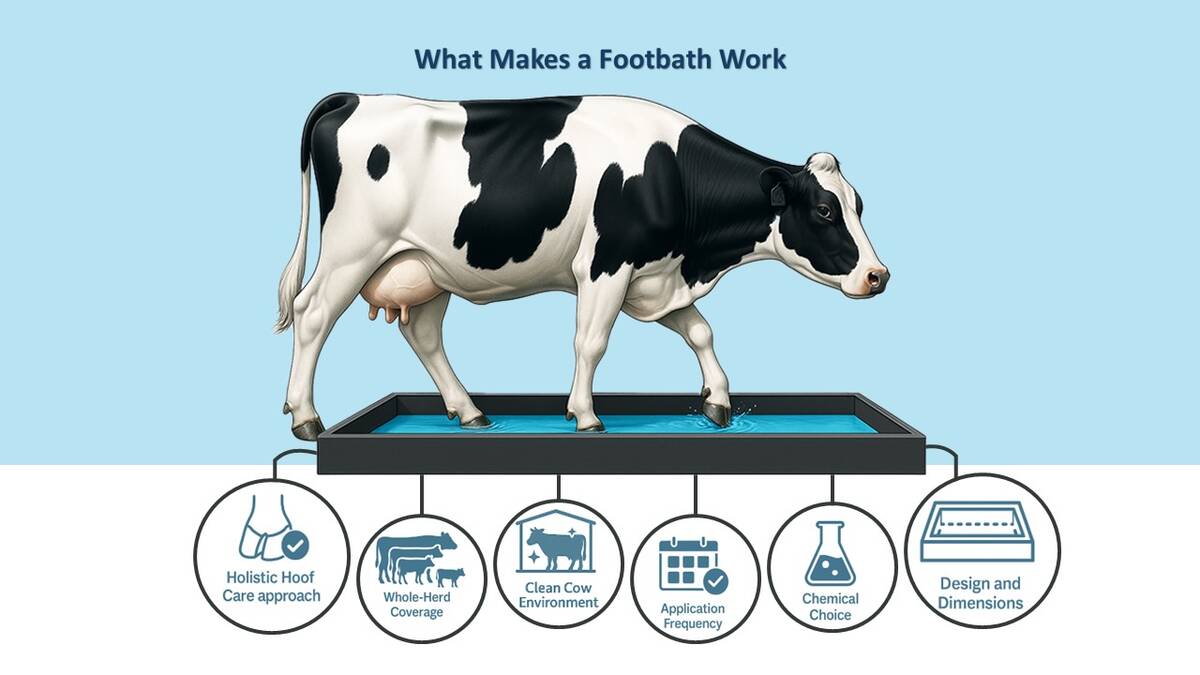

It starts with design. Research from Wisconsin and elsewhere has shown that length and width significantly influence effectiveness. A bath must be at least three metres long to ensure that each rear foot is immersed three or four times during passage. And it should be narrow enough (50 to 60 centimetres at the base) to keep cows walking single file, not side-stepping along the edges. If cows can avoid the treatment, they will.

Chemical selection matters. Copper sulfate, used at three to five per cent remains the most reliable option for controlling digital dermatitis, consistently reducing lesion incidence and severity. However, its rising cost and environmental impact are ongoing concerns. Formalin offers similar efficacy but carries serious health risks and is increasingly restricted. When used, strict safety measures are essential. Maintaining solution pH between 3.0 and 5.5 is also important, as effectiveness declines outside this range even when concentration is correct.

Antibiotics in footbaths are not recommended, as they provide no added benefit and contribute to resistance. Copper-free commercial blends are gaining attention, but results are mixed. Only products supported by independent research should be considered. In practice, copper sulfate and formalin remain the most effective choices.

Even the right product fails when management is inconsistent. The bath must be refreshed before it becomes overly contaminated with manure. In most cases, this means changing the solution after every 150 to 200 cow passes. Farms with cleaner cows can stretch to approximately 300 passes, whereas if cows are very dirty, even 150 passes might be too many. Waiting longer allows the active ingredients to become neutralized, making the bath ineffective.

Frequency of use should match the level of risk. In herds with active outbreaks of DD, footbathing four times per week is a reasonable starting point. These sessions should be done on consecutive days whenever possible, as consecutive exposure builds cumulative chemical effect and limits bacterial rebound between treatments. Once the disease is under control, frequency can be reduced to two or three times weekly. Skipping weeks or applying footbaths irregularly undermines progress and allows DD to re-establish itself.

It is also important not to overlook animals outside the lactating herd. Heifers and dry cows, though often asymptomatic, can carry and shed the bacteria responsible for digital dermatitis. Excluding them from footbath programs creates a constant risk of reintroducing infection just as they enter the milking group.

Effective control often begins in these pens. If digital dermatitis is present in the lactating herd, prevention should start with dry cows and heifers. Breeding-age heifers can develop early lesions well before calving, and dry cows may carry dormant infections that flare up after freshening. Including these groups in the footbath program, even once a week, can reduce the infection reservoir and improve long-term control.

Perhaps most importantly, the footbath must be understood as one component of a broader program. It will not compensate for poor alley hygiene, infrequent hoof trimming, or inconsistent lesion detection. On farms where alleys remain chronically wet or trimming is delayed for months, even the best footbath protocol will struggle to maintain results. Conversely, when used as part of a system that includes clean alleys, regular trimming, proper lesion treatment, and good recordkeeping, the footbath becomes a reliable and cost-effective line of defense.

Farms should periodically evaluate their footbath protocols: measure the bath, count how many cows pass between changes, review chemical concentrations and pH, and observe how cows move through the system. Small adjustments like adding length, narrowing the base, or refreshing more often can produce significant improvements in effectiveness.

A properly managed footbath is not complex, but it must be consistent. When used correctly, it supports daily disease prevention, protects herd productivity and reduces long-term treatment costs. In the ongoing challenge of managing digital dermatitis, the footbath remains one of the most practical tools available provided it is built, maintained and used with purpose.

Amir Nejati has a DVM degree and a Master’s degree in Animal Science from McGill University and serves as a dairy cattle specialist at Clearbrook Grain & Milling in British Columbia