Glacier FarmMedia – It sounds like science fiction, but some day there may be a fertilizer that only activates once the plant tells it to.

That’s an oversimplification, but it’s the premise behind a researcher’s prototype for a “smart” fertilizer that uses a unique chemical to “listen” to calls for nutrients from the plant roots.

It’s an insight into the concept of soil as a living organism, an idea people are just beginning to understand, said Maria DeRosa, a professor of chemistry at Carleton University in Ottawa.

Read Also

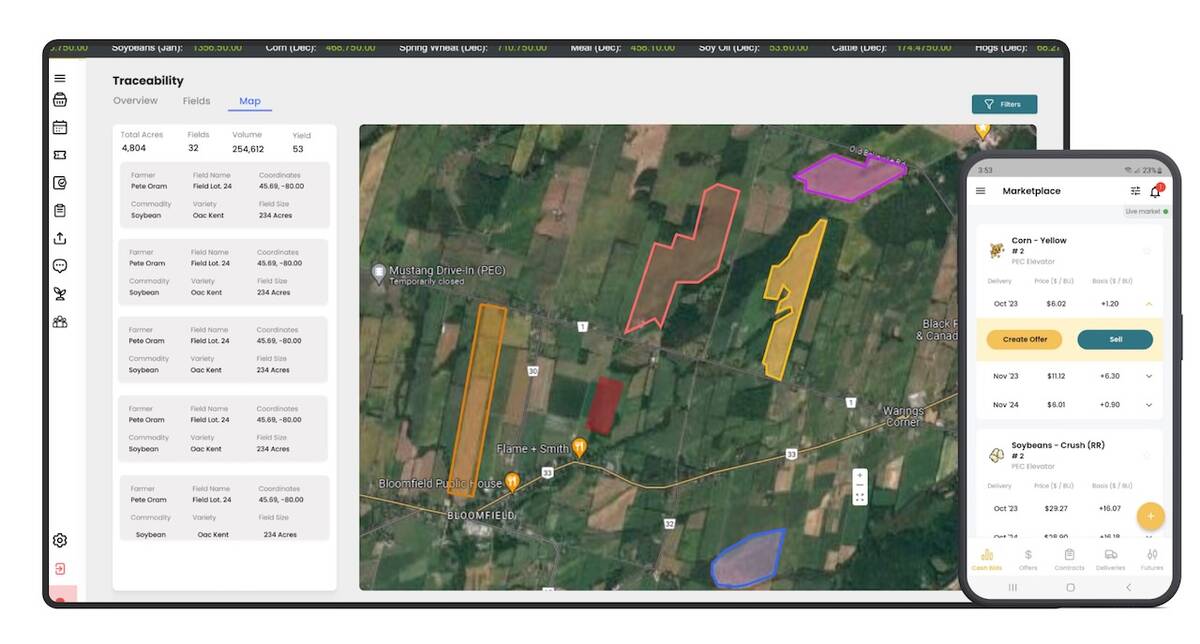

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

And although there’s still a lot of work to be done before the fertilizer is commercially viable, the underlying concept opens possibilities for other precision solutions to farmers’ crop input decisions, not to mention the world’s environmental challenges.

Why it matters: Targeted delivery of fertilizer to plants would prevent nutrient waste that affects soil ecology and would increase efficiency.

“If we could protect the fertilizer and only release it exactly at the moment the crop is ready to take it up, we might be able to be much more efficient with (fertilizer) and create way less of an environmental impact, potentially saving money for the farmer because they’re only fertilizing for the plant,” said DeRosa.

In a nutshell, the process is facilitated by a piece of DNA called an aptamer, which is stored in the chemical coating of a conventional-looking urea pellet.

“It’s just like any other fertilizer you’ve ever used, it’s just coated a different way,” said DeRosa.

The aptamer folds into a molecular-size “pocket” that attaches to a target molecule in the soil, creating a sensor that can detect when the plant needs nitrogen. Once a message is detected, the aptamer is triggered to release nitrogen through the coating into the plant roots.

“The coating’s very thin so hopefully it’s not too much more cost and not too much more weight and all that stuff you have to consider when you’re dealing with fertilizer,” DeRosa said.

Although a prototype has been tested extensively in lab and greenhouse environments, the time is coming for study under field conditions.

“In a lab- and greenhouse-type environment we were able to show we could improve nitrogen use efficiency by up to 80 per cent when we have the coated fertilizer product compared to an uncoated fertilizer product. But in a lab environment there’s no drought and the temperature’s perfect. Now we’re asking if we’re still able to see those gains in an uncontrolled field-type environment,” DeRosa said.

“If we change the way people fertilize wheat, that would be a big game changer.”

Medical connection

Agriculture was the furthest thing from DeRosa’s mind when she started her work with aptamers. Her focus was on human health.

“I was looking at how aptamers can be used to deliver a drug to a damaged cell, a cancer cell or a diseased cell, while not targeting a healthy cell,” she said.

Meanwhile, Carlos Monreal, a now-retired researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada who is now an adjunct research professor at Carleton, had challenges of his own. He was looking for ways to improve nitrogen use efficiency, something that would prevent fertilizer waste and environmental damage.

It was a mutual student who recognized the connection between what Monreal was looking for and DeRosa’s work with aptamers in the human body.

“There were grad students who had taken some of my classes (in) the summer term with Carlos and listened to what his passion was all about. One of them thought, ‘Hey — that sounds like something Maria talked about in one of her classes when she was talking about drug delivery’.”

Nitrogen was chosen for the prototype, mainly because Monreal was focused on it. But theoretically, the fertilizer could be used as a just-in-time solution for any crop input, DeRosa said.

“A lot of issues in agriculture are partially delivery problems. A pesticide that doesn’t actually target the pest can impact other species,” she said. “Same with a herbicide that is released into the environment instead of only targeting the weed. We started with nitrogen but phosphorus is another limited resource we need to worry about. I think a lot of issues could be mitigated by this strategy.”

DeRosa said the process could be optimized.

“It’s just a matter now of finding those signals that are the key to unlocking the coating and finding the aptamer that is appropriate for the event.”

Starting with wheat and canola

The prototype, which at this point lacks a trade name, is intended for wheat and canola. DeRosa said a goal will be to find as many crops as possible that share the same aptamer/signal relationship.

“Wheat and canola are not very similar so the fact that we found one signal that united them in one product was sort of a test gauge for us that this could be something we could generalize. The big-picture people will be more receptive to the idea of one solution. This is a new nitrogen solution that can work for all sorts of different crops as opposed to a niche.”

Now that she’s worked with aptamer delivery systems in both soil and the human body, DeRosa thinks the soil may actually be the more complex of the two.

“The range of possibilities in the soil is so large. There’s so much variability. It’s a big challenge to try to do targeted delivery or targeted interventions in such a complex medium.”

Based on what is known about the science to date, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has granted DeRosa approval to conduct field trials on the prototype.

While seeking partnerships, she said she has talked to producers and gathered their input.

With little exposure to the agriculture community before, she said she was pleasantly surprised by farmers’ open-mindedness and their current use of precision agriculture.

“I came in with the false impression that this is not a field where lots of innovation is taking place,” she said. “But actually interacting with farmers and funding agencies that are involved with agricultural work and finding that they’re so excited about innovation, that they’re so leading edge and looking at what the latest science is in so many different areas, was eye opening for me.”

Jeff Melchior is a contributor to the Alberta Farmer Express. His article appeared in the Nov. 15 2021, issue.