For years, Ontario agronomists have pointed to changes in air pollution from U.S. industries as the reason for the rise of sulphur deficiency in north-of-the-border crops.

Why it matters: Back in 1990, southern Ontario was at the heart of a widespread “dark red” patch of high sulphur deposition, but by 2015, not just the dark red but also the light red, orange and yellow zones had disappeared. Southern Ontario now lies within a dark green zone. That means new knowledge is needed to understand the need for sulphur supplementation of Ontario crops.

Read Also

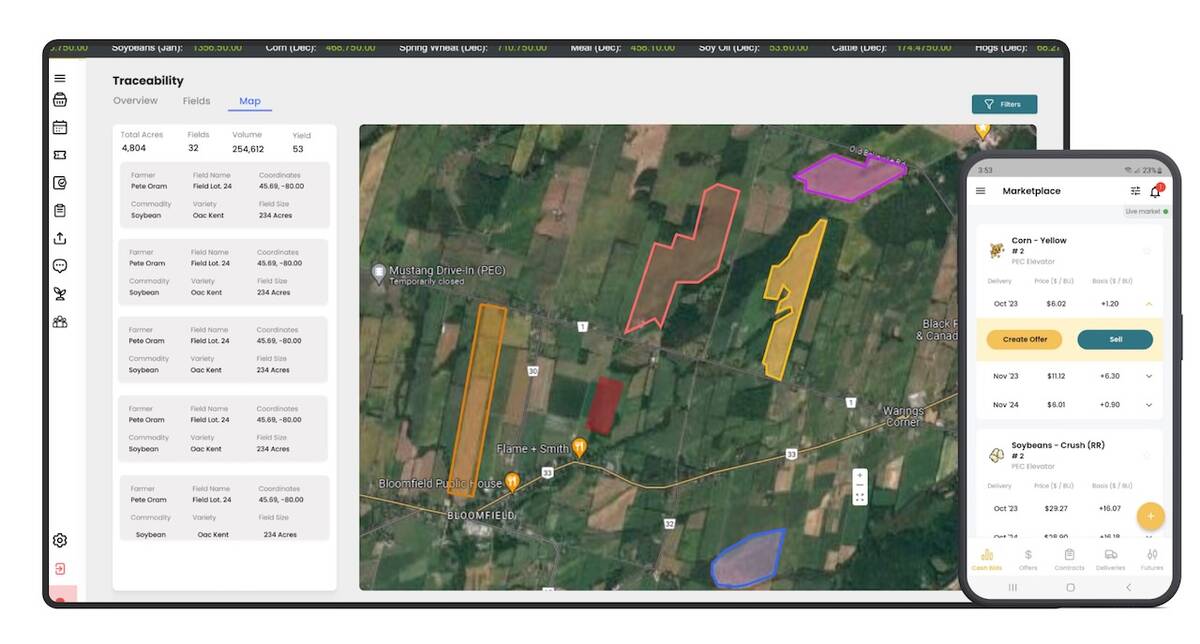

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Audiences at the recent FarmSmart Expo learned there may still be hotspots of sulphur deposition, and researchers need farmers to help find them.

“These maps are to such a large scale, they show almost all of southern Ontario with one single colour,” explained John Lauzon, associate professor in the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Sciences.

Recent Ontario research on winter wheat, alfalfa and canola indicates varying degrees of yield response to some type of sulphur fertilizer, either sulfates of potassium or ammonium, or elemental sulphur. The element is easy on the finances because it’s a byproduct of the oil industry and cheap to transport in a concentrated form.

At a meeting this winter of the Ontario Hay and Forage Cooperative in Mount Forest, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) forage specialist Joel Bagg told attendees “there were some dramatic improvements in fields where there was ammonium sulphate application” during the summer of 2017.

Lauzon joined forces with OMAFRA soil fertility specialist Jake Munroe to update farmers at FarmSmart on sulphur deficiency. Their take-home message was partly based on already-completed work indicating the potential for yield increase as a result of sulphur application, but it was equally about encouraging attendees to help hone in on what Lauzon says is an inadequate understanding of sulphur’s ups and downs in Ontario soils.

They’d like farmers to host test plots aimed at determining which parts of the province are still what Lauzon referred to as “hotspots” for atmospheric deposition of sulphur, and which areas could, by contrast, benefit from sulphur application. They’d also love to know more about possible yield response in corn and soybeans.

To support the case for sulphur application, Munroe drew first on Peter Johnson’s research in winter wheat from 2011-14 looking at average yield response to applications of five, 10, 20 and 40 pounds per acre. Optimum response from a financial basis was 10 lb. per acre. The lowest yield response as a result of this rate was an average one bushel to the acre increase in 2013 — a poor year for winter wheat, when the average yield on the non-sulphur control plots was just 80.2 bushels per acre. But the top response to the 10-lb. application over the four-year study was 4.7 bushels to the acre in 2014.

Potential for yield response has also been shown in Ontario alfalfa. On seven sites studied from 2013-2015, there was yield response on five sites, totalling an average of one tonne of dry matter per every five pounds per acre applied.

This research noted the response to elemental sulphur was essentially equal to the application of sulphate-based fertilizers, not surprising, given alfalfa’s continued nutrient needs throughout the growing season and into the following spring.

Speaking to Farmtario, Johnson noted elemental sulphur would certainly not have led to similar results in the winter wheat study, given that the crop’s nutrient needs are much more immediate. Well-timed sulphate-based fertilizers, either potassium sulphate or more commonly ammonium sulphate, are required in wheat.

Lauzon noted gypsum was also used historically as a sulphur source in Ontario fields, stretching as far back as the 1700s. But that once-common practice fell by the wayside once it became clear in the first half of the 20th century that industrial pollution was providing agriculture with free nutrients. It’s still used, but much less frequently due to the possible presence of impurities.

In canola, work in 2013-14 indicated a yield response in four of 10 sites in Ontario. But similar efforts have not been undertaken in the much more widely grown corn and soybeans. Lauzon and Munroe encouraged farmers to get in touch with them if they’re interested in trying out some test plots to learn more about sulphur deficiency in those crops.