There’s more than one way to grow high-yielding wheat, but focusing on soil health and measuring the impact of different practices are places to start.

Those are two things that grain producers Norm Lamothe and Andy Timmerman of Cavan and Stratford, as well as Jeffery Krohn from Elkton, Michigan, say have helped improve their wheat crops.

Why it matters: Knowing whether a production practice has value requires data and analysis. Growers can combine both data and soil health to achieve high winter wheat yields.

Read Also

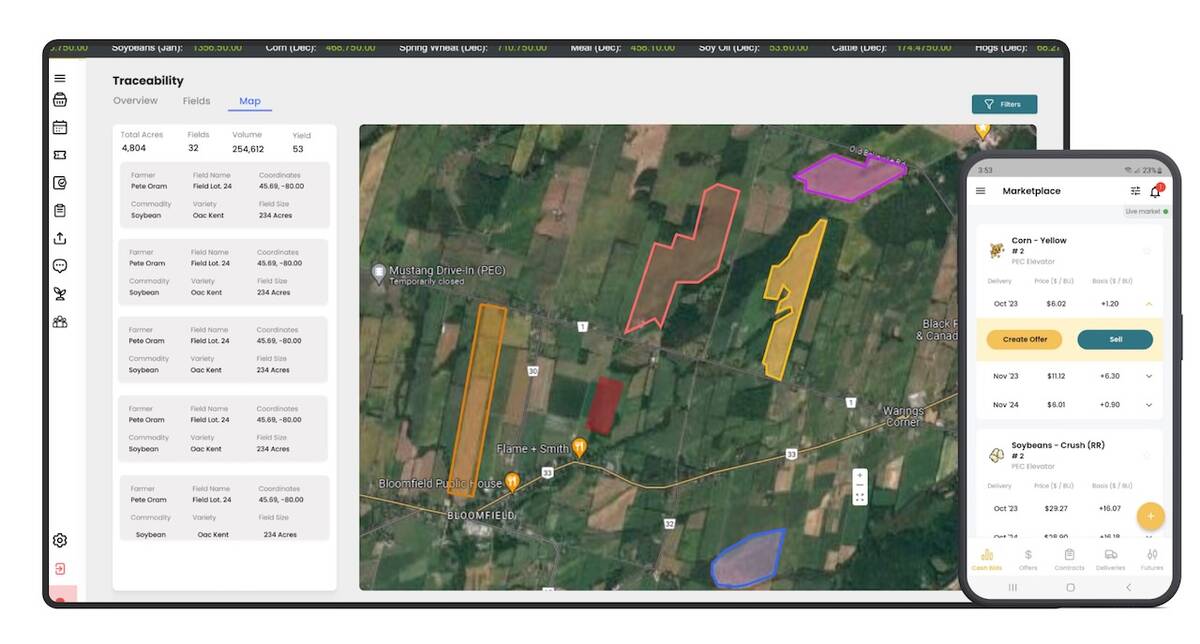

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Each grower shared production strategies and experience as participants in the Yield Enhancement Network’s (YEN) 2022 winter wheat competition during the 2023 Ontario Agricultural Conference. While their approaches differ, each reiterated the importance of testing, verification and emphasizing profit over yield.

Organic amendments, fertility credits

Lamothe runs a diverse Peterborough-area farm, with cash crops as the primary income source. He strives for diversity within the standard corn-soybean-wheat rotation through incorporation of a fourth crop.

His farm was determined to have the highest yield potential in the 2022 YEN contest, and Lamothe says he has seen big gain from small grains — that is, the incorporation of crops such as oats and barley into his rotation prior to wheat seeding.

The inclusion of small grains provides a range of benefits, including breaks in pest and disease cycles, the opportunity for more cover cropping, a more spread-out annual workload, and earlier planting of winter wheat.

“One of the things we found with soybeans is it was extremely difficult to meet those target dates that allow us to grow a large wheat crop,” says Lamothe. With small grains, he can more easily plant winter wheat as soon as possible, ideally in mid to late September.

Organic amendments such as mushroom compost and manure comprise a critical part of Lamothe’s fertility regimen. Nitrogen (28 per cent) is applied via split application.

The roots and residues left by active cover cropping — red clover seeded in winter wheat being the most important but not the only component — has helped reduce the need for additional nitrogen. He says samples taken at the end of winter and before the second application indicate he had gained nitrogen availability in some areas as residues broke down.

Lamothe says he has yet to apply growth regulators and typically does not need to use herbicides. Fungicides have historically been applied at T3 stage, although timing can be a challenge.

Monitoring the cost of inputs and how they stack up against crop prices is a constant task, and Lamothe conducts field trials to determine the most profitable approach.

Little things at the right time

Krohn took the top spot for highest yield, netting 165.92 bushels per acre in the 2022 YEN competition. He attributes the achievement to “doing a lot of little things at the right time.”

Two such things are a low seeding rate of 800,000 seeds per acre (a number that increases if planting is delayed) and narrow, five-inch rows. Krohn estimates the combination of both strategies has brought yield increases between five and 15 per cent.

“We have no secrets. The program we have, like everybody else, is we’re trying to plant early. We’re trying to plant by Sept. 15, or at least get started by Sept. 15, depending on the crops we’re harvesting.”

Like Lamothe, Krohn sees a direct link between soil health and yield. He has observed a correlation between high yields and high levels of soil carbon. Heavy covers, minimum tillage and manure are all pillars of a wider agronomy strategy.

Pest pressures (namely aphids) are generally low, resulting in infrequent insecticide applications. Krohn prefers to apply fungicides at both stage T1 and T3. If herbicides are required in the early season, they are applied in tandem with fungicide.

Regarding nitrogen, Krohn splits applications three ways, starting with an “early-as-possible” application, sometimes when the ground is still frozen. The second application occurs at the second node stage, while the third occurs at flowering.

“The more days we can have that plant green and grain fill, the more yield we’ll get,” says Krohn. “We harvest as soon as we can get it through the combine. Usually that’s around 18 per cent moisture. Our local elevators will take it wetter than that but I haven’t seen a combine yet that can grind through 20 to 22 per cent moisture.”

Krohn adds residual nitrogen must be considered, even in his low organic matter soils. Studies on his farm have shown application rates above 135 pounds per acre do not correlate with higher yields.

“Our break-even for wheat is 100 bushel per acre and sometimes on a dry year didn’t get 100 bushel per acre across the farm. I try to manage nitrogen the most [to] save a few dollars if we need to, if the weather looks like its going to be dry.”

Fertility and tests

For Timmermans, accounting for background fertility and detailed soil testing helped net 150.19 bushels per acre and the second-place position in the YEN competition.

He says variable rate technology, including for phosphorus, potassium and magnesium applications, and early application of nitrogen and sulphur help the wheat “wake up and get moving” in the early season.

A first nitrogen dose is applied with potash shortly after the snow is gone on his Stratford-area farm. A second shot goes on in the second half of April, along with a small amount of boron (one-third of a pound per acre).

A last nitrogen dose is given at the early flag stage. Timmermans says he likes a late application because it gives flexibility.

“We can make some last-minute decisions. It’s kind of like Y-dropping corn,” he says.

In past years, Timmermans has applied fungicides at the T2 stage, but has since observed little response and is likely to change strategies.

Similarly, he hopes to reduce the amount of applied nitrogen from high 2022 levels (178 pounds per acre) as it has resulted in little direct benefit.

An active soil testing program is key to Timmermans’ management plan, although his approach has evolved from large zone sampling to smaller grid sampling, then the development of management zones.

He says soil data continues to reveal a lot about the relationship between fertility and yield. Elevated potassium levels, for example, have shown little positive yield impact, while higher levels of magnesium have.

“I think growing decent wheat is all about the right balance,” he says, adding on-farm tests can be invaluable.

“Probably everybody needs to do more just on farm … what happens on your farm may not happen across the fence.”