Every farm is different and what technology works on one may not suit the other.

According to representatives from farm groups, environmental groups and municipal governments, understanding this truism is critical to finding solutions to Lake Erie’s algal bloom troubles.

Why it matters: Investigating phosphorus filtration technologies for drainage systems and ones that work at the individual farm level, can help improve the Lake Erie ecosystem while providing practical knowledge to policymakers when devising potential regulations.

This sentiment is the main philosophy behind a recent $600,000 project, the investment coming from the federal Great Lakes Protection Initiative, to develop and test technologies that remove phosphorus from water flowing through field drainage systems.

Read Also

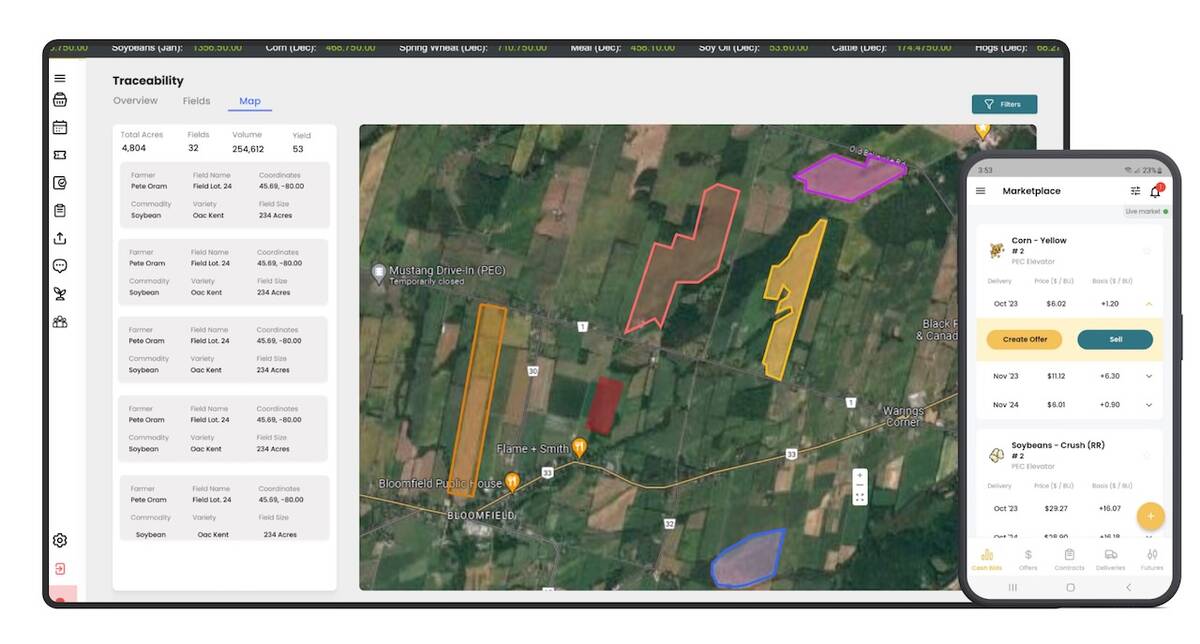

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

This farm-focused project was launched by the Thames River Phosphorus Reduction Collaborative, a group comprising agricultural organizations, municipalities, conservation authorities, First Nations, and environmental non-governmental organizations working to find ways of meeting Canada’s commitment to a 40 per cent reduction in total phosphorus entering Lake Erie.

The project’s initial steps involve finding and implementing phosphorus filtration technologies on farms throughout the Lake Erie basin. According to material from the Collaborative, this specifically means “Low–tech passive systems using beds of sorptive materials (woodchips, steel slag) that react to and bind with phosphorus.”

Charlie Lalonde, project co-ordinator for the Collaborative, says the initiative is looking specifically at technologies adaptable to field drainage systems because phosphorus loss can be a reality on any farm regardless of production practices. Currently, the provincial average for phosphorus loss is about half a pound per acre.

“There’s many factors …. Cover crops help, using the 4Rs helps, but there’s still loss. Even if everything is being done there’s potential for loss,” says Lalonde. “The ability to implement systems to intercept phosphorus on farms represents the last barrier in drainage systems.”

At a recent field demonstration of the first filter system installed as part of the initiative, Louis Roesch, a grain and livestock farmer from Kent-Bridge, and director with the Kent Federation of Agriculture, says his priority is understanding how much phosphorus he is actually losing and when he is losing it.

“A bad regulation can close a business. We need to have the data first. Then we have something to follow,” he says.

Randy Hope, mayor of Chatham-Kent and the project’s co-chair, also reiterated during the event that data generated from the phosphorus filtration system on Roesch’s farm, as well as those not yet implemented on other farms, will provide context for how Ontario farmers are doing when it comes to reducing nutrient runoff.

This will provide policymakers with greater context when it comes to imposing potential regulations, while helping the agriculture community as a whole understand and alter current best management practices.

Hope also said one of the goals of the Collaborative organization is to develop a “menu” of technologies that can help others find solutions for all farm types and locations. This includes American farmers who Hope says may not be as advanced in proactively managing nutrient loss.

“It’s not saying this one is going to be used in another (production) system. We’re inviting innovation. The important part is it’s flexible,” he said.

Technology to reflect farm diversity

Lalonde said a handful of different filtration technologies will be tested at different sites. Similarly, the characteristics of each farm test site will differ in soil type, whether it’s part of a livestock or crop operation, topography, and other characteristics. Together, this will help determine how different technologies work in a diverse array of agricultural systems.

Farmer participation in the project is voluntary and Lalonde said the project is being run through the local agricultural federations. He and his colleagues hope to have a handful of sites operational by October, giving them the ability to start measuring how much phosphorus is being lost between late fall and early spring — the most acute period for phosphorus loss. Measurements will be carried out over the following three to four years.

Municipal water treatment systems could benefit

Nicola Crawhall, project lead for the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, another participating group, adds there is interest in expanding what’s learned at the farm level to larger, municipal drainage systems.

“In-field systems are very small and can only deal with a certain amount of flow. We’d need more capacity to do it at municipal treatment systems, but size is a problem,” she says.

“It would need to be the size of a shipping container. We are almost taking vegetable wash systems and scaling them up, or taking municipal systems and scaling them down.”

Regardless, Crawhill, Lalonde, and Hope all separately expressed the need for phosphorus filtration, and possibly reclamation, systems to be as affordable as they are customizable.

The cost estimate for Roesch’s filter system in a 25-acre field is $10,000. However, those demonstrating the system said they anticipate being able to reduce that cost as they learn more about each system.

Filtration system on Roesch farm

- The system comprises two holding tanks to manage overflow during heavy precipitation events.

- Phosphorus levels in the water are measured before and after entering the filter.

- Measurements taken before illustrate how well the farm holds phosphorus, while measurements afterward calculate the system’s reduction effectiveness.