Parts of southwestern Ontario have higher than normal levels of fall armyworm.

Traps placed south of London, particularly within Essex County, have seen multitudes of moths this fall.

“Similar to last year, we are seeing – when I say ‘we’, Ontario, the Great Lakes area, Ohio, New York, Quebec even – reasonably high levels of [fall armyworm] moth catches in our traps, starting in August, mid-August, but even still now,” said Tracey Baute, field crop entomologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

Read Also

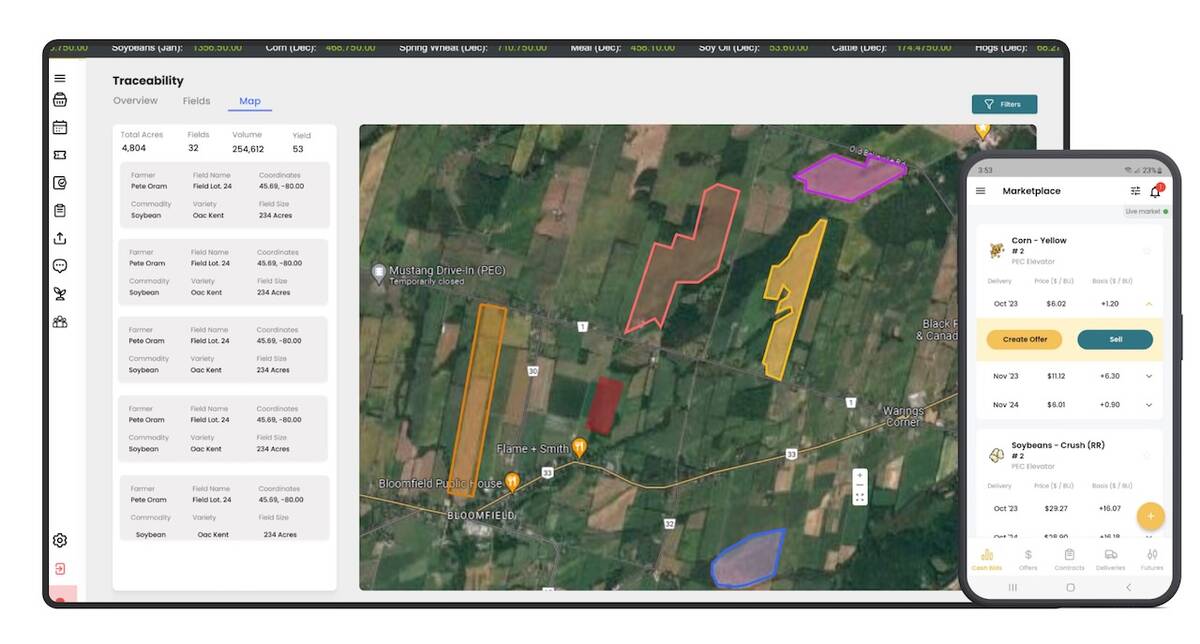

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Why it matters: If fall armyworm populations become large enough, crops planted in fall could suffer damage.

“This flush has me somewhat concerned…. Because we’ve had summer-like weather still in September, it should enable at least some development to continue, and so I expect at least some fields could be at risk with the larvae moving in and feeding on any newly emerging crop.”

Winter canola, cover crops and forages are most vulnerable to armyworm and should be monitored for larvae feedings, she said.

In the past, the pest mainly focussed on corn crops but wasn’t a major concern because corn is mature by peak flight time. Only recently did armyworm become more of a concern in other crops.

[RELATED] Eastern Prairies’ wet conditions may curb insect pest risk

“Texas has seen higher levels of fall armyworm in the last few years. They overwinter there and that increases our risks of more flights eventually making it here and that could be a problem,” said Baute.

Fall armyworms mainly feed on foliage but if they get large enough, they can clip through tissue and harm the growing point, particularly in canola and alfalfa.

Baute said growers should watch for foliar feeding and larvae until temperatures consistently stay below 13 C.

“They can scout probably once a week, at minimum, and if they do still find larvae that are actually feeding, and they’re small enough, they could apply insecticide to protect the plants – more likely for canola.”

There are no established thresholds for fall armyworm in fall-planted crops. It depends on the level of injury or stand loss that could impact the crop’s winter survival.

“It is a matter if fall seeded crops can be at risk, especially going forward, with climate change and seeing these pests overwintering more successfully probably further up in the U.S. We will see this more frequently,” said Baute.

Insecticide control may be necessary when 25 per cent of plants show feeding damage and larvae are still actively feeding, though a frost event will kill larvae.

“Coragen is a good one. Not all the crops may have armyworm on the label, but Coragen is registered on canola and forages, and it would provide good protection against the larvae.”

For pesticides to be effective, the larvae must be 2.5 centimetres or smaller.

Climate change may provide better overwintering conditions in the future.

“We are getting milder and milder winters, [the pest] is able to more successfully overwinter and start their migration earlier in the season… It’s just going to continue when we look at climate change models,” Baute said.

She recommends that growers learn more about this pest and scout appropriately.

“If we continually see this occurrence, we may want to start encouraging growers who are going to be planting their winter canola and their newly seeded forages to potentially put up traps directly in those fields so that they are aware of their local population, and knowing when and if that field is at risk.”