Conservation authorities in southwestern Ontario are leveraging federal funding for projects aimed at reducing phosphorous loading in waterways. In the Essex region, this includes a tile main installation cost-share program that’s proving to be of great interest to local farmers.

Why it matters: Cost-share programs can help farmers finance drainage projects.

The Canada Water Agency is providing four conservation authorities – Upper Thames, Lower Thames, St. Clair, and Essex Region – with a combined $44.5 million over four years to combat nutrient pollution through agri-environmental programming. The Essex Region Conservation Authority received $6.3 million of the total.

Read Also

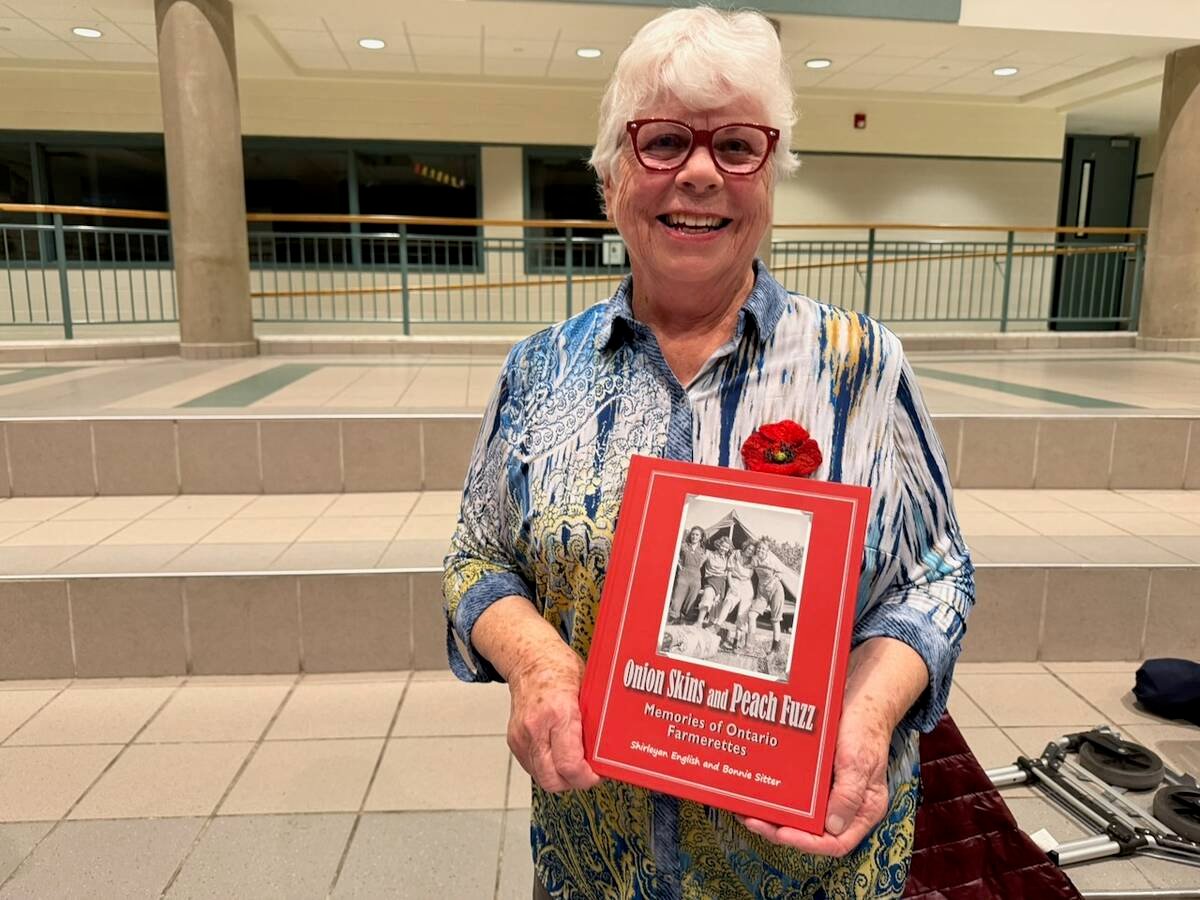

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

Beginning in 2025, Essex launched the “Clean Water – Green Spaces” initiative providing funding for cover crops, soil testing, and other projects similar to those offered by the other three conservation authorities.

Its tile main cost-share program, however, is unique.

Tile mains, also called header tile, channel water from smaller lateral tile to a single outflow source. Designed in part to limit erosion at the ditch bank – and as a result reduce total phosphorous loading – single outflow points also allow for greater ease of flow control, among other benefits.

But in Essex and parts of Chatham-Kent, the flat landscape and prevalence of drainage ditches means many tile systems do not feature tile mains. Instead, lateral tile is often installed directly from the ditch edge.

“The reason for that is because of the extensive drainage network we have. Sometimes there also isn’t enough fall, so you can’t put in a header,” says Katie Stammler, water quality scientist with the Essex Region Conservation Authority.

The tile program provides farmers with $12 per linear foot of installed tile main. In the 2024-2025 fiscal year, 6,640 feet (2,024 metres) of header tile was installed across five projects. In 2025, the authority received applications for 35 tile header projects, with some farms applying for more than one.

Stammler says there has been a notable uptick in interest around the agri-environmental programming offered by the authority. It originally advertised no maximum per project or farm for the tile program, but soon decided a cap of $40,000 per farm business was required in order to “support as many projects and farms as possible.” The capped amount was deemed sufficient to cover the majority of expenses for single large projects, or a couple of smaller ones.

Stammler said header tile projects are sold out for 2025, as approximately one-third of the total available incentive funding this year, for this project type, was reached. “We will not be able to fund all of the projects applied for in 2025 and are reviewing our process for applying for and distributing funds for 2026,” she said.

Stammler adds those interested in the tile program have communicated a variety of motivations for doing so, including ecological concern for nutrient loss from their fields, as well as frustration with plugged lateral tile — often from inquisitive animals — and damage to laterals incurred when drainage ditches are cleared.

“People want to do it. It’s interesting to hear their reasons. Altogether, not just the header tile program, there’s a lot of interest. We’re hearing from people we never had talked to before.”

Lindsay Dean, drainage superintendent with the Town of Essex, also says she has been receiving positive feedback from farmers about the tile main program. Like Stammler, she says converting more field edges from four-inch lateral tile ends to a single main will go a long way to improving ditch bank stability.

This will in turn reduce the cost of maintaining drains by lowering sedimentation rates, and thus the need for dredging. It will also make it easier keep drainage ditches clear by mowing, and improve management of invasive phragmites — a highly prolific and aggressive grass.

“We do a lot of mowing,” says Dean, reiterating the density of drainage ditches throughout the wider area. “We’re also managing weeds and cat tails, and other things from a growth perspective. A lot of these drains, you can’t mow them easily without hitting tile…There’s added cost if you damage tile.”

Popular as the tile program has been, Stammler highlights an important issue – whether tile mains genuinely do limit phosphorous loading on their own is still unclear.

Indeed, she says measuring dissolved phosphorous – when the nutrient is dispersed in water – coming out of subsurface drainage can be a challenge. In part for this reason, and the desire to continue supporting nutrient management and soil health, Stammler and her colleagues continue devoting funding to a variety of agri-environmental programs.