Soil is full of life, essential for nutrient cycling and carbon storage. To better understand how it functions, an international research team led by EMBL and the University of Tartu (Estonia) conducted the first global study of bacteria and fungi in soil.

Their results show that bacteria and fungi are in constant competition for nutrients and produce an arsenal of antibiotics to gain an advantage over one another. The study can also help predict the impact of climate change on soil, and help us make better use of natural soil components in agriculture. Nature published the results on Aug. 1, 2018.

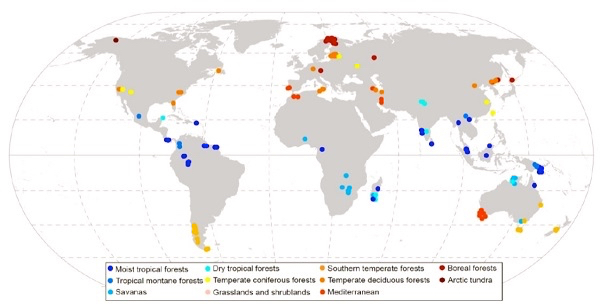

Research on the soil microbiome requires scientists to get their hands dirty. Over the course of five years, 58.000 soil samples were collected from 1450 sites all over the world (40 subsamples per site), that were carefully selected to be unaffected by human activities such as agriculture. First authors Mohamad Bahram (University of Tartu) and Falk Hildebrand (EMBL), together with a large team of collaborators, set up this massive project, gathered samples, and analysed the 14.2 terabyte dataset. Of the 1450 sites sampled, 189 were selected for in-depth analysis (see Figure 1 below), covering the world’s most important biomes, from tropical forests to tundra, on all continents.

Global microbial war

Only half a percent of the millions of genes found in this study overlapped with existing data from gut and ocean microbiomes. “The amount of unknown genes is overwhelming, but the ones we can interpret clearly point to a global war between bacteria and fungi in soil,” says Peer Bork, EMBL group leader and corresponding author of the paper.

Overall, the bacterial diversity in soil is lower if there are relatively more fungi. The team also found a strong link between the number of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria and the amount of fungi, especially those with potential for antibiotics production such as Penicillium. Falk Hildebrand: “This pattern could well be explained by the fact that fungi produce antibiotics in warfare with bacteria, and only bacteria with adequate antibiotic resistance genes can survive this.”

Read Also

Ontario’s other economic engine: agriculture and food

Ontario Federation of Agriculture president, Drew Spoelstra, says Ontario’s agriculture and agri-food sector should be recognized for its stability and economic driving force.

Effects of human activity

When comparing data from the unspoiled soil sites with data from locations affected by humans, such as farmland or garden lawns, the ratios between bacteria, fungi and antibiotics were completely different. According to the scientists, this shift in the natural balance – that probably evolved over most of the earth’s history – shows the effect of human activities on the soil microbiome, with unknown consequences so far. However, a better understanding of the interactions between fungi and bacteria in soil could help to reduce the usage of soil fertilizer in agriculture, as one could give beneficial microorganisms a better chance at survival in their natural environment.

Their results show that bacteria and fungi are in constant competition for nutrients and produce an arsenal of antibiotics to gain an advantage over one another