Analysts think African swine fever could destroy China’s hog herd, forcing it to significantly increase meat imports.

African swine fever is about to unleash the most profound changes in meat and feedgrain markets that farmers will see in their lifetime, says a market analyst.

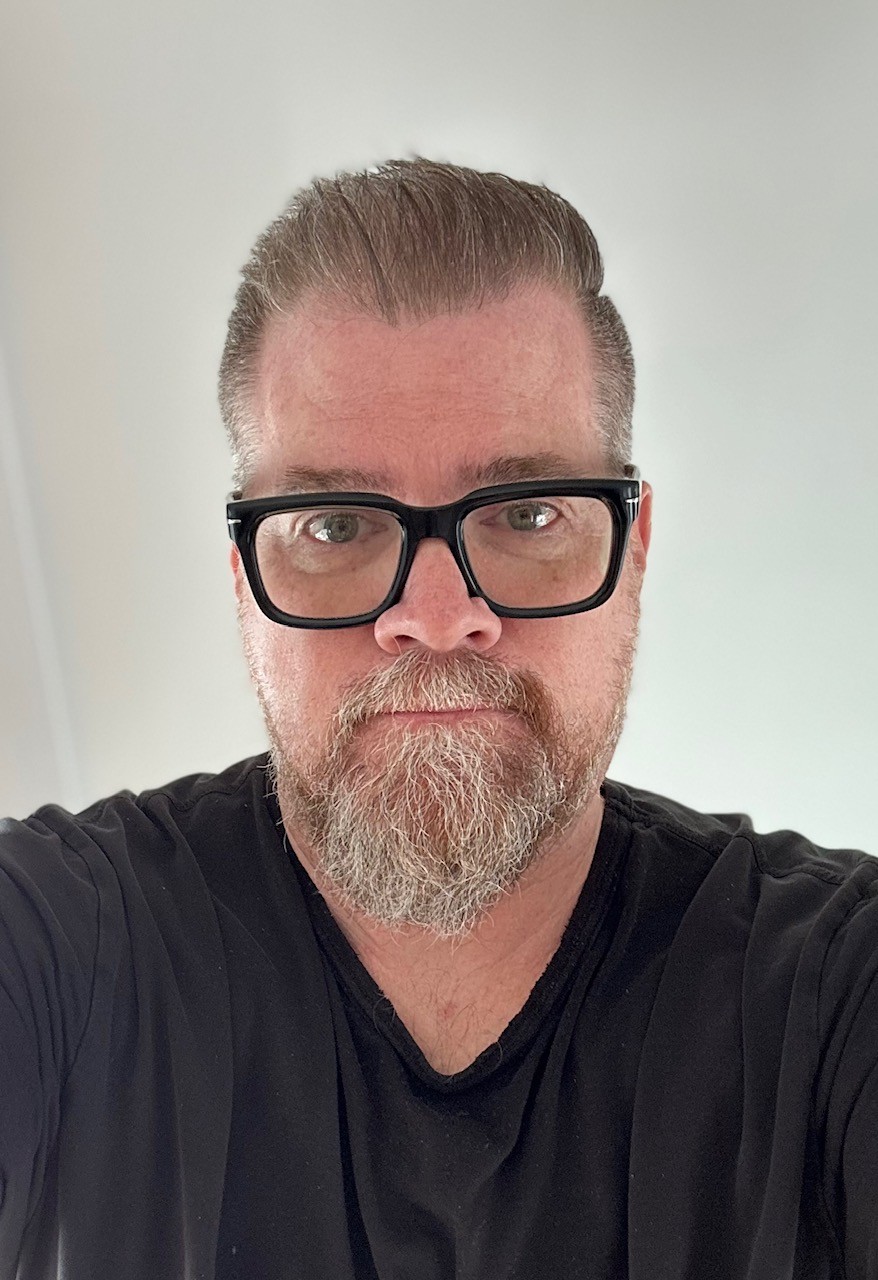

Shawn Hackett, president of Hackett Financial Advisors, said a “pandemic of infection” in China is going to lead to surging demand and prices for North American meat products.

“It looks to us like we are heading into a meat protein bull market in hogs, chicken and beef,” he said during a video podcast on the subject.

Read Also

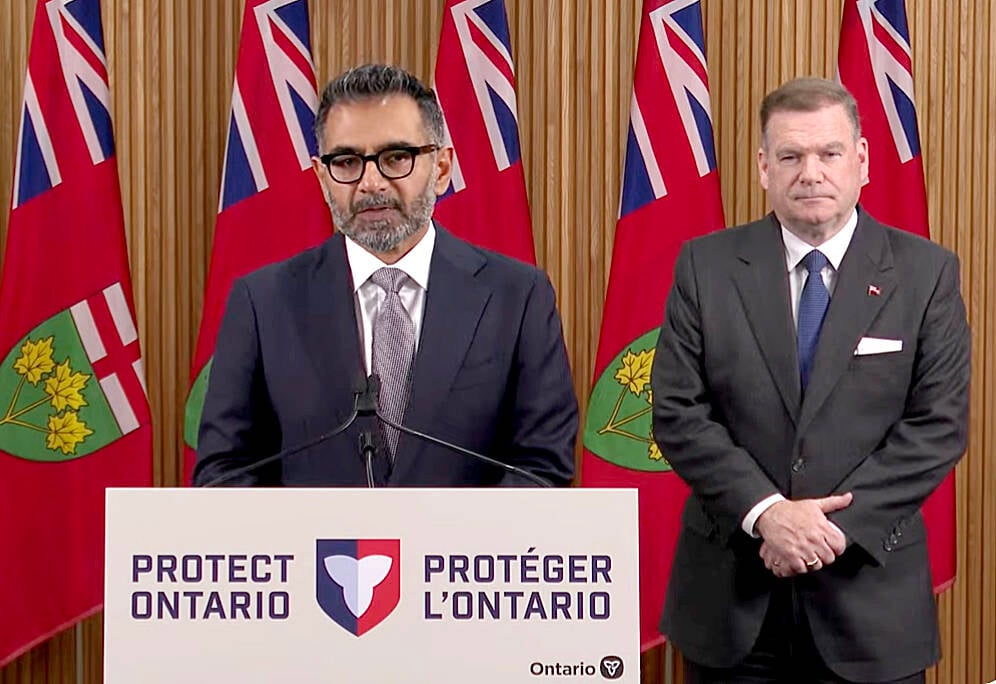

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

“We think this is a once in a generation kind of anomalous event.”

Why it matters: Pork producers in Canada may be positioned to fill in supply shortfalls caused by the spread of African Swine Fever. As the Chinese pork industry restructures, it could also create new markets for feedgrains.

Hackett said the rapid spread of the disease in China is going to require “draconian action” by the government.

Half of China’s pork production comes from backyard operations, which are difficult to monitor and control.

He said the only way for the government to get on top of the problem is to shut down those small operations and move their production to large corporate farms that have proper biosecurity procedures in place.

That transition will cause significant supply disruptions with some people forecasting a 30 per cent reduction in China’s hog herd.

Hackett is using a more conservative estimate of a 10 to 15 per cent decline over the next year.

“Just to give you an idea — that reduction in the Chinese pig herd would be equal to almost the entire pig herd of the United States,” he said during a video podcast on the subject.

China would lose six million tonnes of pork supply, which is close to what the world’s top three exporters together ship out annually.

“We simply do not have the exportable supply to handle a reduction in Chinese supply of this magnitude,” said Hackett.

In addition to the shrinking supply, he expects to see a contraction in demand from consumers who mistrust the government and mistakenly worry that Chinese pork meat is tainted. They will look for other sources of protein.

“We think that chicken and beef are likely to see a tsunami of replacement demand away from pork while this crisis is underway,” he said.

If 10 per cent of Chinese pork demand shifted to beef because of changing consumer preferences, it would equal the combined exports of the world’s top four exporters.

Beef and chicken prices would have to rise dramatically to entice extra production and increased exportable supply. Hackett said there are already signs that is beginning to happen with beef.

Jorge Correa, vice-president of market access with the Canadian Meat Council, agreed that demand for Chinese pork may drop.

“The consumer in China is losing confidence in their own industry,” he said.

Correa said that could lead to increased demand for imported pork, and Canada is well situated to meet that demand.

China is 95 per cent self-sufficient in pork supply with the other five per cent imported from North America, South America and Europe.

African swine fever has spread throughout Europe, making it an unlikely supplier, and the U.S. is facing stiff tariffs into the Chinese market, so Canada, Brazil and Chile would be the likely candidates to pick up business.

“In Canada we haven’t seen that increase yet,” said Correa.

He thinks that is partially because Canada has been shipping more pork to Mexico instead, a market where the U.S. is also facing new tariffs.

Correa thinks it is unlikely that Chinese consumers will switch from eating pork to beef or chicken because they are pork lovers, consuming 40 kilograms per capita per year. As well, beef is more expensive than pork.

Hackett is convinced the Chinese situation will create a massive increase in pork, beef and chicken demand, which will also do wonders for feedgrain prices.

That includes soybean meal. Many people believe China’s shrinking hog herd would be bad for the soybean market, but Hackett said the backyard operations that would be shut down don’t use soybean meal in their rations. It is used by the larger farms, which would be increasing their hog herds.

“We could actually see an explosion in bean meal demand a little further down the road,” he said.