Glacier FarmMedia – The outcome of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine is unknown, but for Ukrainians it’s already a human tragedy of suffering, death and destruction, but also brave defiance.

It’s likely to get worse — not just for Ukrainians and Russians, but for many of us.

Why it matters: The Russian invasion of Ukraine has already affected markets and will continue to do so as countries and citizens react to instability.

Read Also

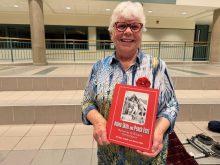

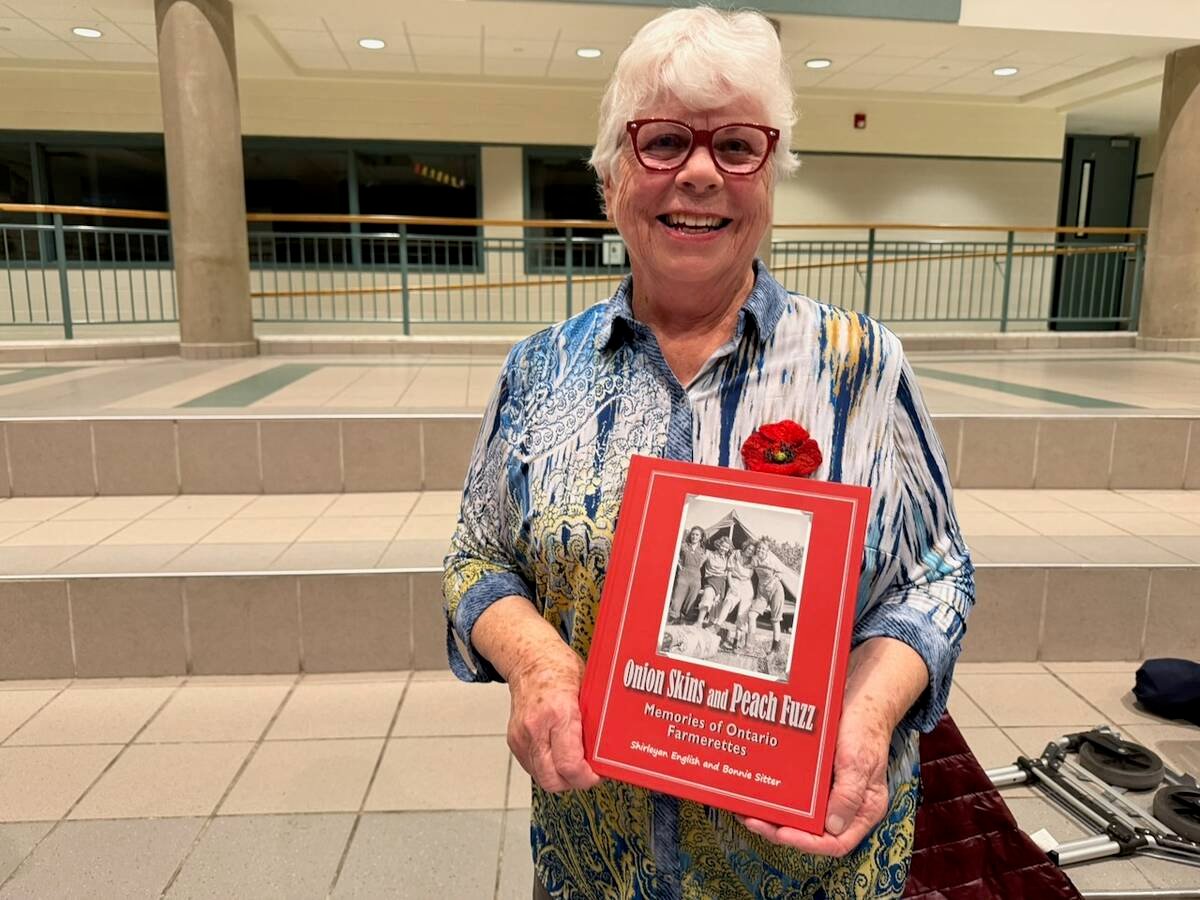

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

“Although commodity exchanges are already in chaos, ordinary folk have yet to feel the full effects of rising petrol bills, empty stomachs and political instability,” the Economist said in its March 10 newsletter. “But make no mistake, those things are coming…

“We observe that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is triggering the biggest commodity shock since 1973, and one of the worst disruptions to wheat supplies since the First World War.”

In 1973 the ‘Great Grain Robbery’ was perpetrated by the Soviet Union, which collapsed in 1991, 74 years after it was founded in the wake of the Russian revolution led by Vladimir Lenin.

Ironically, Putin’s invasion, which began in 2014, is part of his fanciful plan to resurrect the Soviet corpse.

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, land of Siberian gulags and inefficient collective farms, where the proletariat pretended to work and government pretended to pay them, relied on wheat imports from the United States and Canada to feed its livestock and sometimes its people.

In 1973, after two poor crops, the Soviets bought 10 million tons of mostly wheat, snookering the U.S. Unaware the Soviets were short of food, the Americans subsidized the sales, which were so large they pushed domestic grain prices, and ultimately food prices, through the roof.

“We’re going through a bit of a similar situation right now,” said Ted Bilyea, Distinguished Fellow with the Canadian Agricultural Policy Institute (CAPI), during an online meeting to discuss the impact Russia’s war will have on agriculture and food security.

The Food and Agriculture Organization’s world food index is the highest since 1973, Bilyea said.

World wheat prices were at a 14-year high earlier last month. Chicago benchmark wheat futures prices soared more than 50 per cent since the invasion, hitting US$12.94 a bushel March 9, up from about US$7.58 at the start of the year.

“The end game is a lot of people are going to be hungrier,” Bilyea said. “And yes, the prices will simply lower demand in not a very good way, but it will lower demand and that will be how we’ll get through this crisis. People will eat less.”

People will also eat less meat and more pulses and “fake meat” made with plant protein, said Sebastien Pouliot, principal agricultural economist with Farm Credit Canada.

“We’re already seeing people consume less meat than before… less beef, less pork and more chicken,” he said.

Canadian cattle producers were already suffering because of high grain prices following drought last year and the latest increase will make Canadian beef production even less profitable, Pouliot said.

Bilyea predicted such high grain prices will see a shift, especially in Europe, on where meat is produced. Large livestock-producing countries like the Netherlands, Spain and Belgium were already net grain and protein importers. Where production isn’t subsidized or protected, livestock should move to grain and not the other way around, he said.

World fertilizer prices were up dramatically even before the war and are going higher, Pouliot added. Russia is a major fertilizer exporter, but sanctions will cut into sales. He expects this year Canadian urea will double in price from last year, while anhydrous ammonia and ammonium phosphate will jump 65 per cent.

World oil prices are up dramatically too, increasing farmers’ diesel bills.

“Pretty much all crops in Canada we expect them to be profitable… even though input prices are going up so much…” Pouliot said.

High grain prices will put pressure on governments and farmers to take marginal land out of conservation programs to produce more grain, said Shane Knutson, president of Polywest Ltd.

“What I do know in the short term, people need to be fed and so we’re going to do whatever we have to globally to try to make sure that everyone gets fed whether that means, as Sebastien pointed out, eating less meat in the short term or doing whatever we need to do,” he said.

Bilyea agreed there’s an incentive to convert marginal land into grain production but said that would be a mistake.

“We are going to destroy ourselves if we go that route,” he said, adding it won’t happen quickly because legislative changes are needed, especially for land set aside to fight climate change.

“It’s… not a good idea to convert grassland to cropland. You know taking cattle off grassland is an insane thing to be doing. We need the grasslands and we need the cattle on the grassland everywhere in the world. I think we have to come up with other ideas of how we are going… to be more productive, intensify productivity in a way that’s highly sustainable.”

A recent study shows the world’s agriculture isn’t as productive as previously thought, he added.

“What we thought was more productivity was actually more land coming into production.”

Grain prices are high and the same applies to oil crops. They were high before the war due to strong global demand relative to supply, Bilyea said. Meanwhile, Canadian and American companies are planning to boost oilseed-crushing capacity to fulfil a growing demand for renewable diesel.

“I do think this situation will affect how fast we go forward with all those things.”

The food-versus-fuel debate has gone on for years, Pouliot said. So far government hasn’t announced any changes to renewable fuel mandates “and I don’t expect them to go away either.”

Bilyea’s advice to the Canadian government is “do no harm.”

“Some of the climate mitigation issues that were being put forward we could just delay those for a bit,” he said. “We don’t need to stop them. We delay them and work them into a more systematic change rather than do things overnight.”

Canada and other nations also need to be more resilient, he said. One way is to rely less on fertilizer imports. Canada is a net exporter of nitrogen and potash but relies on phosphate from the U.S.

“But we could be a leader essentially in recycling phosphate,” Bilyea said. “As you know every city in the world is a phosphate dump essentially and you could just recycle it through struvite back into farms.”

Ukraine and Russia grow mainly winter wheat, which is already in the ground, said Knutson, who has worked in both countries. What’s unknown regarding Ukraine is how well that wheat will be cared for and what will happen at harvest.

There’s uncertainty about who will buy Russian wheat, although China will be one customer, and how it will be shipped as Black Sea ports closed due to the war.

Ukraine can ship grain by truck and train to European buyers, but Russia doesn’t have that option. It has ports in the far east but they lack the capacity to handle all the country’s grain exports, Knutson said.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) forecasts combined Ukrainian and Russian wheat exports will fall 12 per cent, Ag Insider said March 9.

Nations from Europe to Asia and Africa will import less wheat in coming months due to higher prices and reduced supplies from the Black Sea region.

USDA analysts said exports from the two countries would fall to a combined 52 million tonnes this marketing year, down by seven million tonnes from their estimate before the invasion. The reduction would be partially offset by Australia and India, which have ample supplies to sell, the newsletter said.

“The comment in the chat is we need more global co-operation not less…” CAPI’s managing director Tyler McCann said as he concluded the meeting.

“Clearly we’re all part of a global system that needs to work well to make sure we can produce the affordable and accessible food people need to eat.”

– This article was originally published at the Manitoba Co-operator.