On one hand, the federal government stated the obvious when it identified the food system as one of the 10 critical infrastructures supporting Canadians during the pandemic crisis.

After all, who can survive without food?

Nevertheless, the guidance document issued by Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister Bill Blair sent an important signal, one that the industry was desperately waiting to hear — and one that consumers needed to hear.

“We are all going through a period of great uncertainty right now and, as Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food, I assure you that our government is taking all the necessary measures to ensure that Canadians always have access to quality food at affordable prices,” Marie-Claude Bibeau said in an accompanying statement.

Read Also

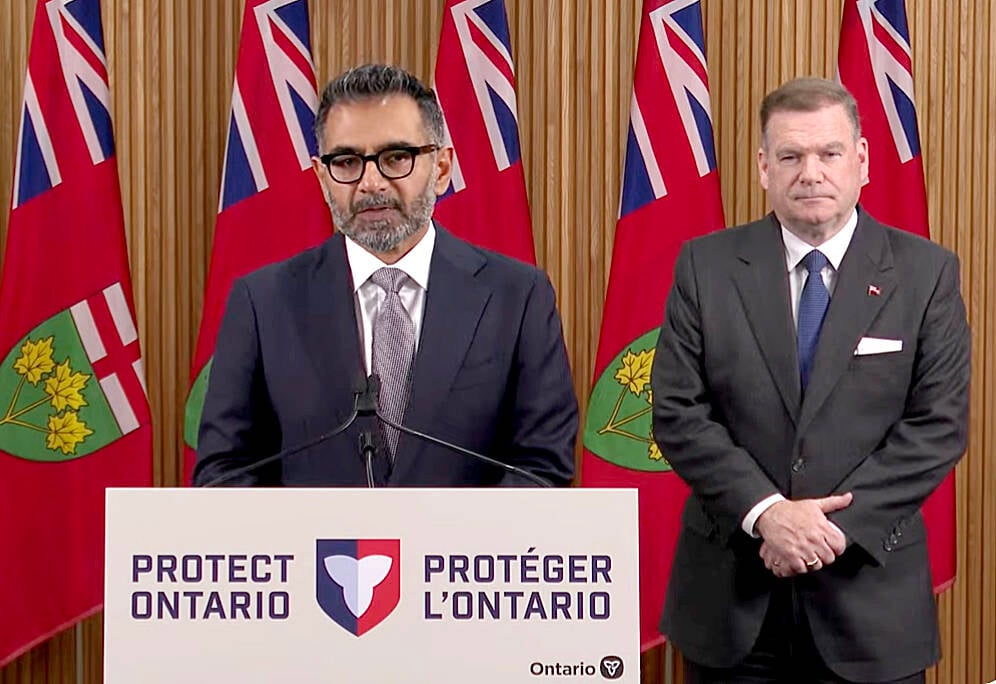

Conservation Authorities to be amalgamated

Ontario’s plan to amalgamate Conservation Authorities into large regional jurisdictions raises concerns that political influences will replace science-based decision-making, impacting flood management and community support.

Analysts are following the fascinating shift in consumption patterns as shoppers stock up on pantry items and food service providers rapidly transition from dining-room service to takeout and delivery.

“It is hard not to miss the lack of flour in the grocery aisles lately as consumers stock up on the ‘essentials’,” said Bruce Burnett, analyst with Glacier FarmMedia’s MarketsFarm said in a research note recently. “A number of stores are just rolling out the pallets of flour into the store and they are picked clean by the end of the day.”

The U.S.-based agricultural lender CoBank has tracked what it calls a “monumental shift” in recent weeks to consumers purchasing nearly 90 per cent of their food at supermarkets, up from 48 per cent.

This has created unforeseen pressures on the supply chains and some have found it hard to quickly adjust.

So far, dairy farmers have borne the brunt of that reality as they dump millions of litres of milk due to sudden changes in market demand from the food service sector. At the same time, the “stocking up” phenomenon has resulted in temporary shortages in some grocery stores.

While some have used this to condemn supply management in Canada, it’s notable that dairy farmers in the U.S. and Europe are in the same boat. It’s a supply chain issue that has nothing to do with how the marketing system is structured.

It’s still important to note that basic access to food is not in jeopardy.

“There is surely a need to reassure the public of our food security,” three leading agricultural economists say in a research paper released in late March.

“Nothing fundamental has changed with regard to productive capacity in the agri-food system — no livestock or plant disease, or a natural disaster (flood, drought, pests, destruction of property) has occurred that destroys food output,” wrote Al Mussell, Doug Hedley and Ted Bilyea with Agri-Food Economic Systems. “Movement of agri-food product from farms through to consumers has been resilient to any number of past extremes.”

That said, they highlight the fact that efforts to streamline supply chains, which in agriculture are often lengthy and involving several intermediaries, might backfire in times like these.

When agriculture is viewed solely through an economic lens, redundancy is a bad thing. If however, it is seen as an essential requirement, a little redundancy in the system makes sense.

If, for example, a major meat processing plant is taken off-line due to a high rate of employee absenteeism or a COVID-19 related isolation order, it quickly spreads back to the farm level. We’ve seen evidence of that already as Olymel has started backing out of delivery contracts.

It’s a worrisome for livestock production systems that depend on delivering a steady flow of animals to market, and which quickly run out of space in barns.

The availability of labour, which was already a critical concern for the sector, could become acute on two fronts. While the federal government has made provisions to allow temporary foreign workers into Canada during the pandemic crisis, the logistics of getting them here at a time when airline operators are drastically reducing their flights schedules are sketchy.

As well, housing, sanitation, and working conditions to reduce the risk of an outbreak will be under extra scrutiny. Similar concerns apply to U.S. and Mexican operations that supply many of the fresh fruits and vegetables available to the Canadian market.

Farming in Canada operates within tight windows for planting and harvest, so even a short-term loss of workers can have a major impact on production.

The one bright spot, at least for some farmers, is that the downturn in the economy due to COVID-19 means increased the availability of workers capable of handing industrial-scale equipment. But there appears to be little by way of infrastructure to connect those workers with the farmers who need seasonal help.

A federal designation of food and its supporting industries as essential doesn’t mean any of these issues evaporate, only that they won’t be relegated to the political backburner.