The 2018 Farm Bill will expire Sept. 30. Simultaneously, the American government needs a new budget in place to open its doors Oct. 1.

It will take a mighty effort for either to get done. In the three months between July 1 and Oct. 1, the House of Representatives is scheduled to be in session just 24 days, while the Senate will sit for 30.

The biggest, most difficult fight will be passing the 2024 U.S. federal budget. In a good year, much of that work goes on behind the scenes as key committee chairs, ranking members and staff debate, schmooze and compromise to hammer out a spending plan that few like, but most can swallow.

Read Also

New Iridium technology helps block GPS spoofing

A tiny new chip will allow Iridium’s Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) signals to be received much smaller devices, create a backstop against Global Positioning Systems (GPS) spoofing.

In a bad year, it can be hand-to-hand combat that often turns into a multi-trillion-dollar game of chicken, with a government shutdown as the ultimate threat.

This year is a bad year, but not for the usual partisan reasons.

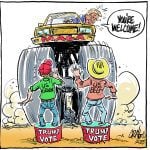

This battle features House Republicans warring with other House Republicans over how deep to cut 2024 federal spending, despite the debt-raising deal hammered out between Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy and President Joe Biden in late May.

“Mr. McCarthy and his leadership team blindsided Democrats … by setting allocations for the 12 annual spending bills at 2022 levels, about [US]$119 billion less than the $1.59 trillion allowed for in the [May] agreement to raise the debt ceiling,” reported the New York Times June 15.

McCarthy also blindsided most Republicans, especially in the Senate, who thought they had a deal with the White House that gave Congress the green light to get both a budget bill and Farm Bill done before the Oct. 1 deadline. Not so.

Now everyone is stuck as moderate Republicans try to remove the monkey wrench that was thrown by a handful of hard-right House Republicans into the already-creaky gears of a deeply divided government.

There are no easy wrench-removal ideas floating around. In fact, reported Politico recently, “GOP hardliners are still fuming over the deal … McCarthy struck with … Biden to raise the debt limit earlier this month, especially a provision that could expand the number of people on federal food aid.”

Ah, yes, food aid, or SNAP — the Supplemental Food Assistance Program that now gobbles up 80 per cent of all Farm Bill dollars.

Democrats see it as an integral part of federal programming to support families in need. Hard-line Republicans view it as a too-costly, fraud-ridden program (despite lack of confirming fraud evidence) that promotes government dependency.

Pragmatic Congress members across party lines, not to mention almost every farm and commodity group, see SNAP as the political bridge to bring broad urban support to government farm programs. Without those non-farm votes, most political handicappers agree, there would be no Farm Bill.

The anti-food aid tactic was also used by Republican hard-liners during the fight to settle on the 2018 Farm Bill. The results, reminds Politico, “helped to sink a partisan House GOP farm bill on the floor. It took another seven months to get the final bill” done.

It wasn’t Democrats who propelled the 2018 bill to victory; it was the “Republican-majority Senate [that] eventually stripped the House GOP’s steep SNAP restrictions from the final legislation” that delivered its eventual passage.

This time around, the Democrats run the Senate and their ag committee boss, Debbie Stabenow, recently announced that “Congress is done discussing SNAP work requirements in the wake of the [McCarthy-Biden] debt limit talks.”

Stabenow’s message didn’t register with McCarthy. “In private,” reported Politico in mid-June, “the speaker has told fellow Republicans that … to appease hard-liners, the party will need to at least push for stricter work requirements.”

Appeasing “hard-liners” may allow McCarthy to maintain his tenuous grip on his job, but it won’t make any farmer or rancher’s job easier if there’s no Farm Bill come Oct. 1.

The Farm and Food File is published weekly throughout the U.S. and Canada. Past columns, supporting documents, and contact information are posted at farmandfoodfile.com.