Anyone with a modest amount of historical knowledge knows that Canada’s Indigenous populations have a long and rich history tied to the land and agriculture.

Indigenous communities in North America were cultivating crops such as potatoes and corn long before anyone from Europe had heard of the crops. Materials from the Manitoba Museum cite evidence of agriculture in the eastern United States dating back 3,800 years.

More locally, bison scapula bones found in Gainsborough Creek in 2018 showed convincing evidence of pre-European contact farming in the Melita region. And agriculture was an undisputedly big part of the Métis way of life in the Great Lakes region. Farms surrounded fur trade posts by the 16th century, and some cereals were being farmed in the 1830s.

Read Also

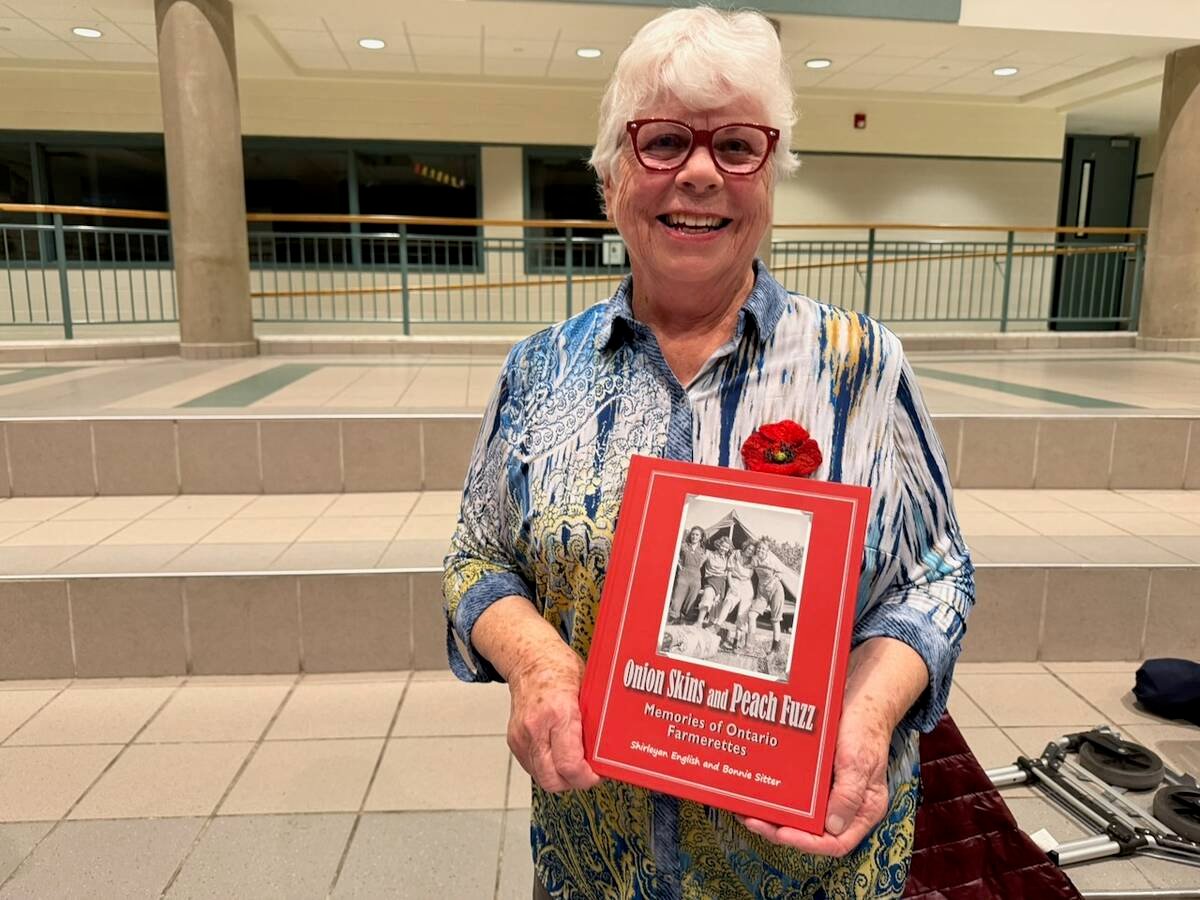

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

When it comes to reconciliation, agriculture presents a unique challenge. How can the treaty rights of Indigenous peoples be honoured in a way that gives them a proper seat at the table when it comes to farming in Canada?

It’s something that groups like the Southern Chiefs’ Organization (SCO) in Manitoba, headed by Grand Chief Jerry Daniels, and the Manitoba Métis Federation, with its agriculture minister, David Beaudin, have been working on for years. I recently had the chance to speak with both about why they feel agriculture is so important, and what still needs to be done.

Daniels and Beaudin share views on several pivotal issues, including engaging youth and the continued importance of food security. Both expressed that, while regular conversations do take place with the Manitoba government, there’s still a ways to go when it comes to proper recognition and reconciliation.

Currently, there are several programs funded by the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership (S-CAP) that would partner with Indigenous communities, such as the Indigenous Agriculture & Food Systems Program and the Indigenous Agricultural Relationship Development Program. Eligible activities include revitalizing traditional food systems; training, skill and resource development; climate change adaptation; increasing Indigenous participation in agriculture; engagement between industry, academia and Indigenous Peoples and the development and delivery of engagement activities.

I was unable to find a list of specific projects that have benefited, although Manitoba Agriculture Minister Ron Kostyshyn highlighted Fox Lake Cree Nation’s Food for All program and collaboration with Brokenhead Ojibway First Nation, Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation and the SCO on bison-related projects.

Meanwhile, both the MMF and the SCO have made strides towards agricultural autonomy through their own programming, including garden box programs, community gardens, climate action plans, bison herds and lobbying for more access to Crown lands.

It seems like both Indigenous organizations and the Manitoba government are eager for relationship building and programming designed to reclaim agricultural traditions tied to local Indigenous history and culture. There are stories like these emerging across Canada.

I think education is another important aspect—not just having Indigenous leaders with ties to the land remind their people, especially the youth, of their rich agricultural traditions, but for Manitobans who descended from settlers to learn that history and those tradition as well. If anything, it will only lead to more common ground between Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous farmers, both of whom are tied to the land in real, rich, and meaningful ways.

Hopefully soon, this country’s fertile soil might produce the right growing conditions not just for healthy crops, but for more healthy relationships built on respect, understanding and a motivation to keep moving forward together.