Employing young Ontarians in agriculture is an uphill battle, but still an achievable task for a forward-thinking sector with sufficient support.

Why it matters: Canada could face a labour shortage in the agriculture sector without engaging key demographics like youth and post-secondary graduates.

The sector’s failure to stay competitive following several increases to Ontario’s minimum wage may have hurt its chances with young Ontarians, especially recent post-secondary graduates, but data shows there are still pathways for youth to make a living in agriculture.

Read Also

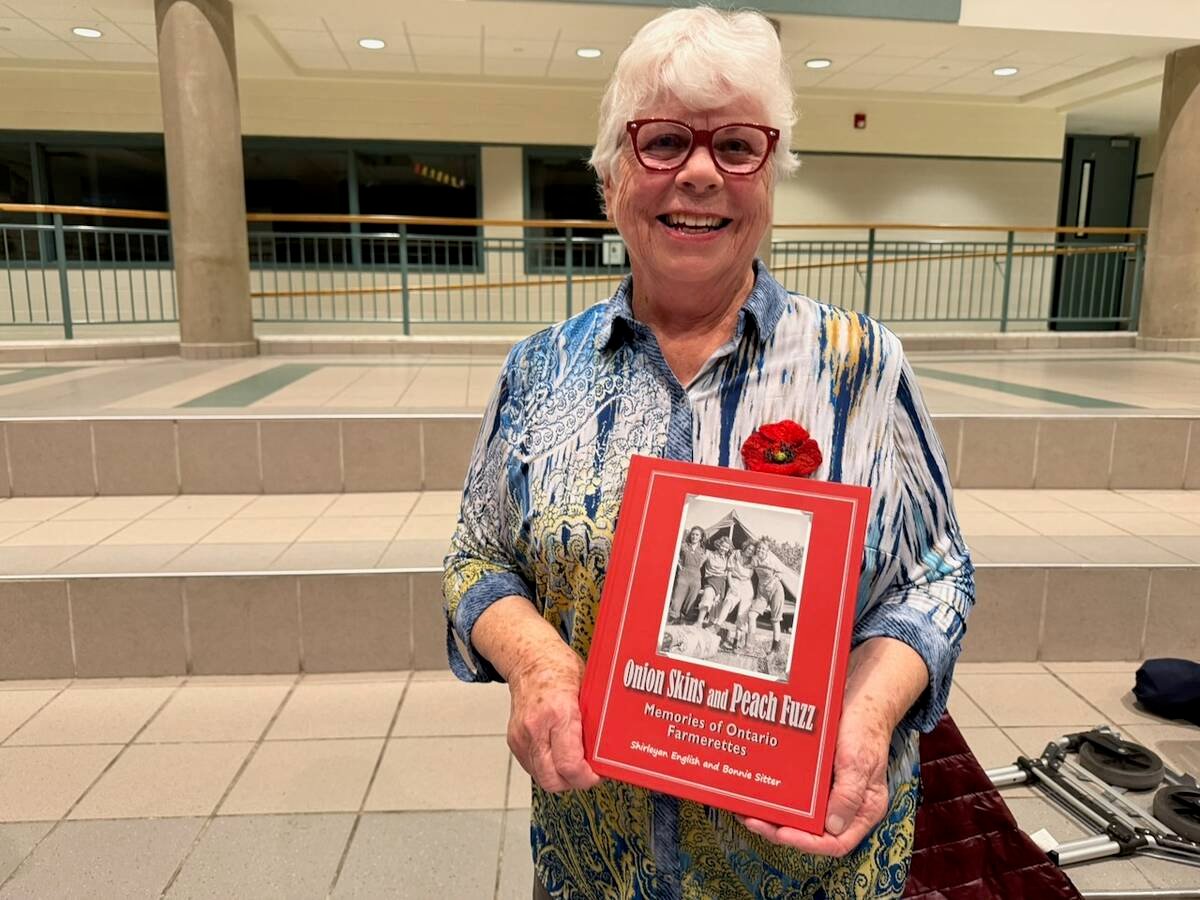

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

One of the main barriers to getting youth involved in agriculture careers is a lack of interest.

Pierre Valley, economic development officer with Bruce County and member of Bruce County’s Workforce Strategy, said the agriculture sector has recently had difficulty employing youth.

“There’s job postings within the industry, but it’s probably one of the lower posting industries out there,” he said.

“The reality is, the agriculture industry has had such a hard time with finding and attracting people over the years, I would say that they’ve almost given up, for lack of better words, going through conventional measures to try and hire people.”

Ellen Gregg, supervisor of employment services with Bruce County, said it can be difficult to find reliable and consistent data on agriculture employment since hiring is often done through existing family and community connections, or word of mouth.

Regular seasonal layoffs in agriculture also make job posting data difficult to analyze.

There are several reasons for these challenges, including difficulties with transportation and the tendency for only those who already have rural backgrounds to show interest in rural jobs. Much of this divide may come from the values and work philosophy of generation Z, though.

“The values that youth have today are completely different than the values of people that are hiring them,” said Valley. “Youth have actually listened to their parents. And the parents have said … since the day they were born, ‘don’t be a slave to the man.’ You know, ‘make sure you have work-life balance.’”

“Their child has now gotten to the point where they’re getting employed, and the child is saying ‘I don’t want to work overtime. I don’t want to work on the weekends. I want to have that work-life balance. Because you’ve told me for the last 15-20 years that that’s what I should be doing.’

And then yet, that person who told them that the whole time, who’s now the employer, is saying ‘I can’t get people to work overtime.’”

According to a 2023 report from the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council (CAHRC), Gen Z showed higher-than-average interest in workplace features like comfortable break rooms, transportation and travel assistance and the opportunity to take days off without pay.

Out of all generations surveyed, Gen Z was the least likely to agree with the statement “I would want to stay with the same organization for as long as I can.”

Some of these values could get in the way of traditional on-farm careers. However, Jennifer Wright, CAHRC’s executive director, said youth in Ontario are showing interest in agriculture jobs.

“When I say there’s interest, I mean we’ve gone from absolutely zero to just a little bit,” Wright said.

“It’s not like, oh, all urban students are interested in agriculture. Most of them still aren’t aware,” she said.

“However, in general, I think we have an opportunity to grow that attraction of young people into the industry.”

Capitalizing on this could involve making some students aware of non-standard jobs within the sector.

“It’s more the work and the thought of the work — like being out in the field, in the heat, there’s other opportunities where you can work indoors and not be outside.”

Wright said the organization still has a lot of work to do to make youth aware and understand what opportunities are available, and what modern agriculture is all about.

“But I would say that we are starting to see a little bit more interest, not just from youth that have grown up in rural environments, but a bit more interest from youth or post-secondary students that are more from urban settings as well.”

Wage disparity?

Wages within agriculture vary depending on the position. Some haven’t kept up with the provincial average, while others may have more growth potential.

According to statistics from the Government of Canada, agriculture managers make an average of $24.52/hour, with agriculture service contractors and farm supervisors slightly lower at $22.50. The Government of Ontario lists the average hourly wage rate in the province as $36.14.

The Economic Policy Research Institute at Western University lists the average annual salary for crop farmers in Ontario as $81,000, with a significant disparity between the entry level salary at $58,000 and senior level at $98,000. According to the job recruiting website Indeed, the average base salary for farm labourers in Ontario in around $20/hour, and $25/hour for farm managers. Ontario’s minimum wage is currently $17.20/hour.

Wright said pay is not always the most important factor for youth when job-seeking, however.

“The jobs are well paid for the work, but it’s the work that people are not as interested in doing,” she said. “Even if they make $1 less an hour working fast food or retail, or whatever it might be. They’re not out in the field, in the heat or working with animals, where it smells.”

This ties back into the problem of recruiting, though Government of Ontario data suggests employment in both management and agriculture positions is on the rise.

Between January 2023-24, management jobs in Ontario grew by 130,700. The agriculture industry saw growth in employment during that period, but only barely, at only 400 jobs added.

Valley said even when jobs pay more than the provincial minimum wage, it still may not be enough to appeal to the younger generation. He also said above-average paying jobs in agriculture have not always stayed competitive with minimum wage increases in Ontario. According to a 2022 report from Policy Alternatives, “all industries with lower-than-average wages, except for agriculture and manufacturing, had increases in employment” following the implementation of the $14 minimum wage in 2018.

CAHRC research suggests Canada’s agriculture sector is in a “chronic labour shortage,” with more than 28,000 jobs unfilled in 2022. Employers will need a new approach to save the sector from further shortages.

In 2023, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) released the What We Heard Report, which identified the challenges employers have in attracting workers citing “rural location, type of work and wages.”

The report aimed to work with provinces, organizations and stakeholders to develop an Agriculture Labour Strategy. CAHRC was listed in the report as a partner working to address labour issues.

Wright said there is still investment needed in the workforce strategy, and the sector has not yet seen the full impact of the report.

“There’s not one solution for everything in agriculture, that’s for sure,” she said.