Decommissioned oil and gas wells may be a risk to the property of farmers and rural landowners according to the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR).

Nicole Michalchuk, senior advisor in the petroleum initiative section of MNR, explained in a webinar hosted by the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA) how Ontario farmers can deal with wells and prevent the illness and contamination they could cause.

Why it matters: There are thousands of inactive and unknown oil and gas wells in Ontario which could be liabilities to landowners.

Read Also

Is Canadian agriculture ready to pivot?

Guests and speakers at the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute’s 2025 conference say Canadian agriculture is at a turning point due to unpredictable factors.

Recently, a hydrogen sulphide leak in Wheatley led to a large-scale evacuation, following which Ontario Ontario Natural Resources Minister Mike Harris reportedly said at a news conference the province is trying to map abandoned oil and gas wells with new technology.

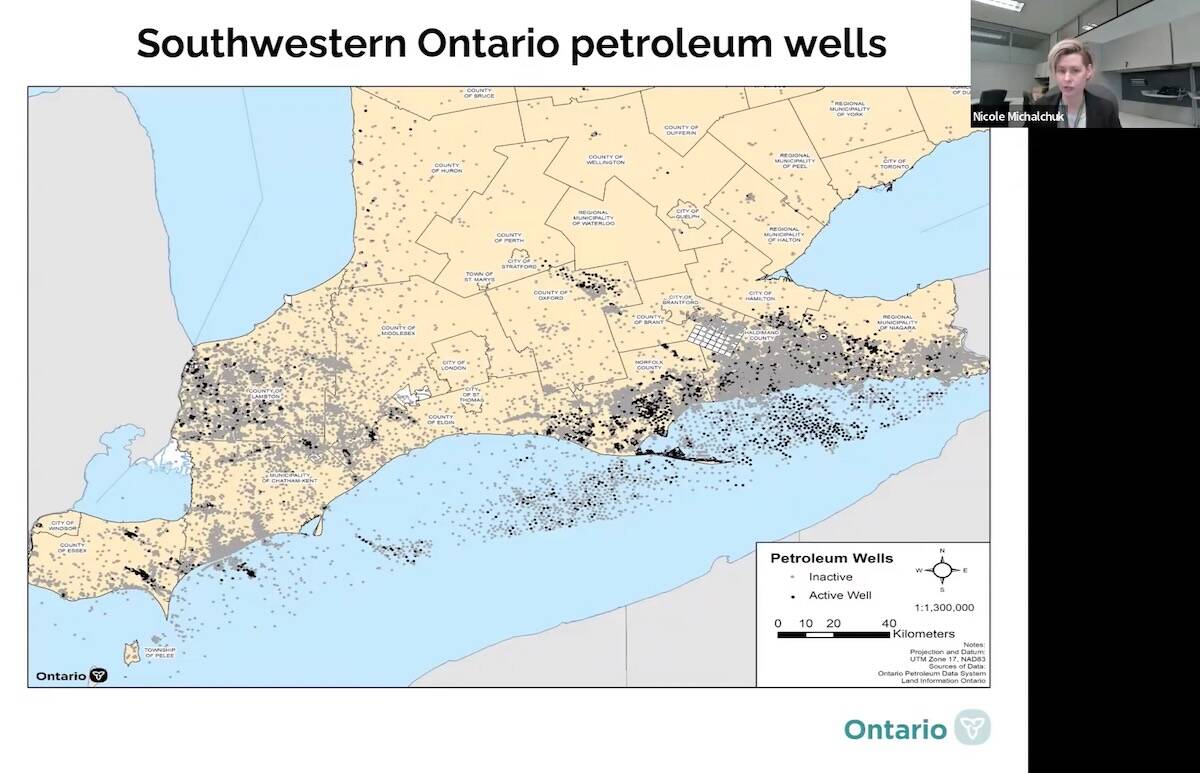

According to Michalchuk, the MNR has records of over 27,000 oil and gas wells in Ontario, thought there are likely more without records, mostly concentrated in southwestern Ontario. Only around 3,400 of them are active.

“These aging wells were drilled and decommissioned decades ago when plugging practices might not have been well-developed and record keeping was extremely limited,” Michalchuk said.

While oil production is no longer a major industry in Ontario, Michalchuk explained the province hs a history of petroleum extraction dating back to 1858.

“The majority of the wells are inactive, old wells … the majority of these wells do not have a license holder, lessee or other viable operator, which means responsibility for the well falls to the landowner.”

She suggested several resources for farmers who don’t know if they have oil and gas wells on their property.

“If you’re not sure if you have a petroleum well on your property, you can do a simple search online to find out if there’s a well record on or near your property.” This can be done at Ontario.ca/oilwells and searching the petroleum map.

The MNR has also created a postcard with more information on how to use online systems to search for wells.

More detailed records can be found at the Ontario oil, gas and salt resources library. Landowners can use this not-for-profit resource centre to access information about wells on their property anonymously.

“Once you see the map of the petroleum wells, you can do a further search by just inputting your specific address or area, and you’ll be able to pull up a well record if it’s there in the database,” Michalchuk said.

“Another way to check is to physically search your property,” she added. “Old inactive wells have sometimes been buried, they might be below the surface, so when doing a search on your property, you can look for debris piles, old foundations, old tanks, partially buried pipes, maybe some stone, brick, wood or clay tiles that might be piled up.”

Consulting with neighbours and community members who may be familiar with your property’s history or even records like aerial photos through libraries could also help.

Funding may be available through the Abandoned Works Program to cover costs associated with plugging the well. Wells may qualify for this funding if “an active operator cannot be identified for the well, other than the landowner” and if the farmer has not “used, benefited from, or intentionally tampered with the well.”

Michalchuk stressed landowners planning new buildings on their property should stop work immediately if they suspect they are building on top of a well, as it could affect the structure through basement leaks.

Many older wells were built with inferior linings and casings. If not properly decommissioned, they can lead to spills in the environment or create a pathway for poisonous gasses like hydrogen sulphide, which could create life-threatening damage.

“These gasses, along with other fluids, can migrate below ground and can affect groundwater quality, impact nearby vegetation, soil and surface water,” said Michalchuk.

Signs of trouble could include black soil staining, vegetation discolouration, gas bubbles in pooling water and a sulphuric rotten egg smell.

If you suspect hydrogen sulphide may be present, Michalchuk recommended to “avoid low-lying areas or confined spaces where toxic gasses could accumulate” and report it to the MNR and Spills Action Centre immediately.