Drunk drivers are more likely to get in an accident because the alcohol in their blood impairs vision and delays reaction time.

University of Saskatchewan biologists have identified a comparable phenomenon in locusts, when the insects are exposed to a small dose of insecticide.

Why it matters: Farmers require a wide range of pesticides to most effectively control pests. Research into how the pesticides affect insects and the environment is key to convincing the public of their continued value and of gaining public acceptance for responsible pesticide use.

Read Also

Footflats Farm recognized with Ontario Sheep Farmers’ DLF Pasture Award

Gayla Bonham-Carter and Scott Bade, of Footflats Farm, win the Ontario Sheep Farmers’ 2025 DLF Ontario Pasture Award for their pasture management and strategies to maximize production per acre.

“If you’re crossing an intersection and a car is going to come and T-bone you, the normal reaction would be to slam on the brakes or speed up or turn,” said Rachel Parkinson, a PhD student in biology at the University of Saskatchewan.

“With these insects (in the study) it’s almost as if they don’t notice that car coming at all.”

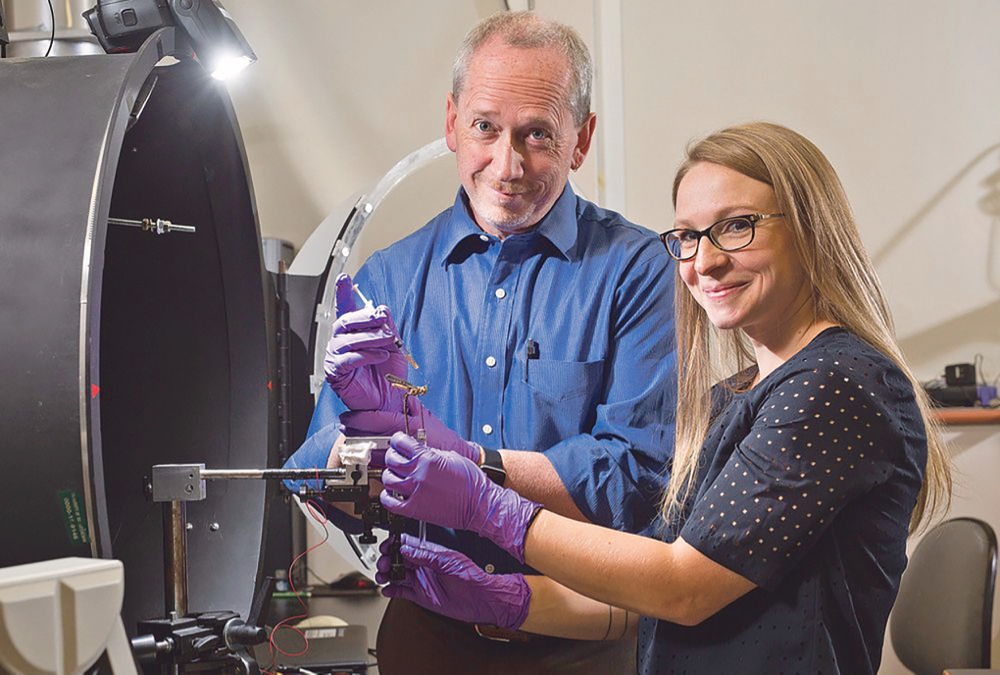

For several years Parkinson and Jack Gray, a biology professor and expert in neural control of animal behaviour, have been studying how neonicotinoids, a class of insecticides, alters the vision and motion detection of locusts.

Neonicotinoids, commonly known as neonics, are widely used in crop production and are applied to nearly every canola and corn seed in North America as a seed treatment.

Previous studies have shown that bees, when exposed to low doses of neonics, struggled to find their way back to the hive and had difficulty navigating.

Parkinson wanted to push beyond that level of knowledge and figure out what was causing the navigation problems.

“The question I was asking was why?”

This month, Parkinson and Gray published an answer to that question in the journal NeuroToxicology.

When exposed to “tiny amounts” of a neonic or metabolites, compounds created as the chemical breaks down, the locusts struggled to turn, glide and stop to avoid collisions.

“Our findings suggest that very low doses of the pesticide or its metabolic products can profoundly and negatively affect motion detection systems that flying insects, such as locusts, grasshoppers and bees, need for survival,” Gray said. “Although they are found in the environment… metabolites are not typically tested for toxicity. Our results suggest they should be.”

To reach that conclusion, Gray and Parkinson placed locusts inside a small, laboratory wind tunnel, about one metre by one metre by two metres.

While the results shouldn’t surprise people because neonics are insecticides and locusts are insects, the findings may explain how neonics affect locusts, bees and other insects, Parkinson said.

“I would argue the experiments I’ve done are really useful for being able to tease out these really subtle effects, which could have major (impacts) on survival… Maybe the harm is happening in these more subtle ways.”

Parkinson has conducted a similar experiment on sulfoxaflor, a Corteva Agriscience insecticide, to see how it affects locusts. She expects to publish the results in about six months.

So far, Parkinson and Gray have focused on locusts because they’re easier to study than bees.

Parkinson plans to study bees this summer, to see if neonics affect their vision and motion detection in the wind tunnel.

This article was originally published at the Western Producer.