THIS IS OUR STRENGTH.

The red letters stand against a dark blue sky on the poster, just above a scene of two men driving a harvester through a rolling wheat field with a white farmhouse and red barn visible in the background.

Why it matters: With hungry troops overseas, the Canadian government during the Second World War had incentive to bolster public opinion of farms as part of the wider war effort.

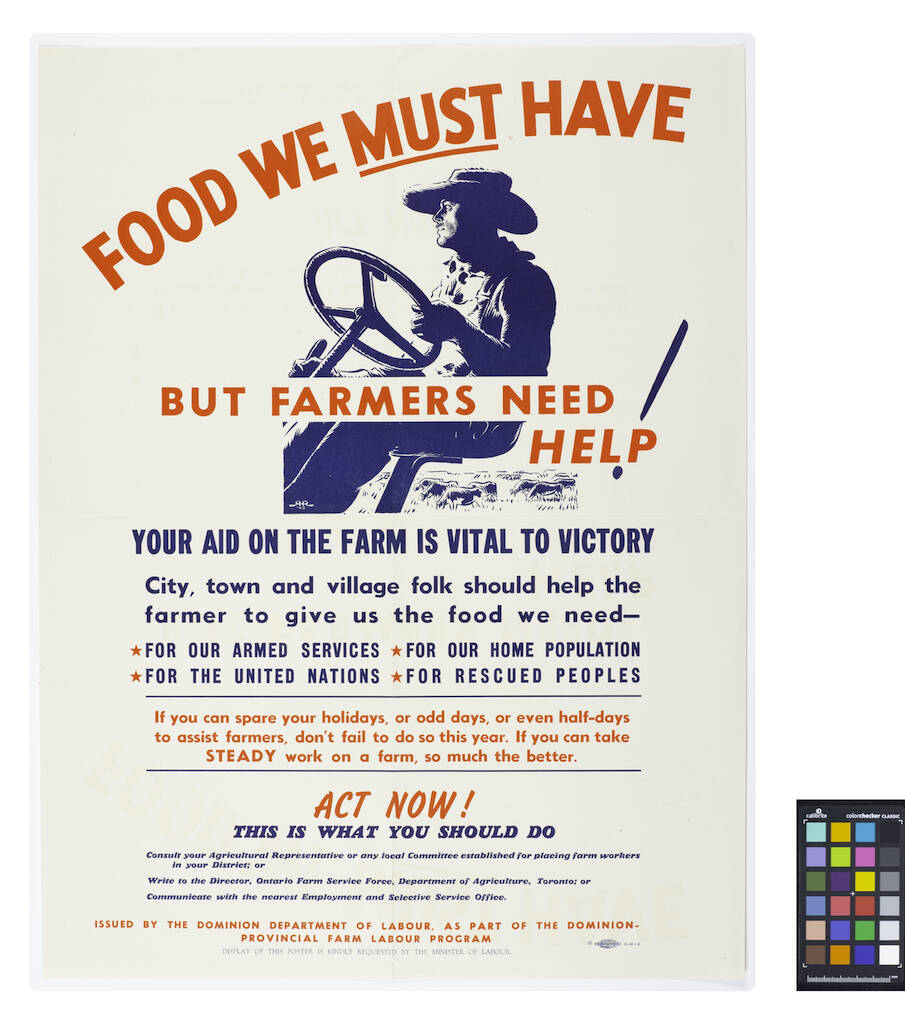

Another tells passersby that “FOOD WE MUST HAVE, BUT FARMERS NEED YOUR HELP,” accompanied by a simple drawing of a farmer on a tractor. Smaller text below encourages “town and village folk” to lend their help to the farmer on “holidays … odd days, or even half-days.”

These and other war-time propaganda posters stand as a window to Canada’s veneration of farmers and agriculture during the Second World War.

Stacey Barker, a historian at the Canadian War Museum, has built a research expertise in Canadian agriculture and food during wartime. To her, such agricultural propaganda images reflect one of the more mundane realities of war: Soldiers have to eat, and that food has to come from somewhere.

Read Also

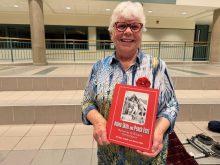

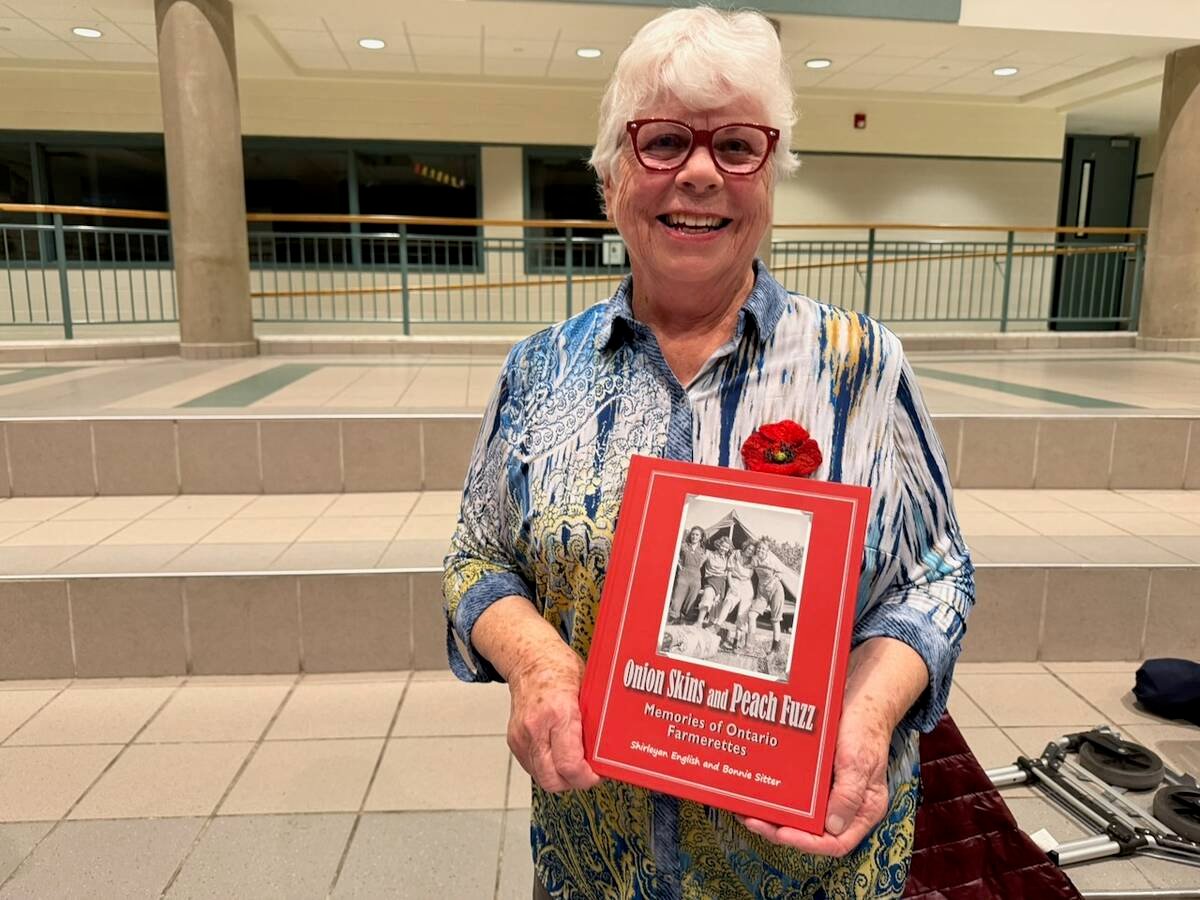

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

Until the United States joined the war in 1941, Canada was the breadbasket of the Allies, she noted.

“Everything gets dominated, and with reason, by the battles and the troops and D-Day,” Barker said. “This is sort of a little more subtle, and it’s not often thought of.”

The pall of the Dirty ’30s

The story of Canadian agriculture during the Second World War is incomplete without considering the historical context.

Farmers in the early ’40s weren’t just operating in a world at war, they were coming off of years of financial devastation. They were in need of a break.

“Farmers (were) coming out of the (Great) Depression,” Barker said. “They had had a very difficult time of it in the 1930s. The Second World War starts and they’re starting to climb out of it, but there’s a lot going on in terms of, ‘What are we going to need to do for the war effort?’”

In the First World War, Canadian farmers were given a clear goal: produce as much wheat as possible. One poster from 1918 proclaims “The World is Short of Bread” and that Ontario must increase its wheat production from 3,700,000 bushels in 1917 to 10,000,000 bushels through “good seed,” “thorough soil preparation” and “early sowing.”

The start of the Second World War saw that supply situation flipped on its head. Farmers had done their jobs too well, and now Canada had too much wheat in storage.

“One of the big things that the government asked farmers to do was grow less wheat, diversify, grow more feed grains, raise livestock, because that’s what Britain needs,” Barker said. “They need protein sources; they need things that are easily shipped. They don’t need as much wheat.”

Pork became one of Canada’s key exports as it could be canned or turned toward long-lasting rations like bacon. According to a 1947 document from The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, production of pork from 1935-39 doubled during the war.

Farming pride

With so much of the usual labour force fighting overseas, the Government of Canada needed to drum up support and a sense of national duty among those who could help farmers at home. That’s where the posters come in, encouraging Canadians young and old to help farmers in any way they could and often featuring similar art and messages to military recruitment posters or other propaganda.

“There was definitely a conflation between the military and this work,” Barker said. “It’s characterized as war work, as service.”

Young Canadians were targeted by farm labour initiatives like the Farmerettes for girls, or the Farming Commandos for boys — notable for its invocation of a military title, much like the Soldiers of the Soil did during the First World War.

“War conditions calling for increased production, heavy enlistment, munitions and supplies requirements have brought about an acute manpower shortage situation throughout Canada,” reads a Farm Commandos recruitment pamphlet. “Agriculture has been among the heaviest sufferers in this regard.”

The slogan on the back of the pamphlet reads, “Let us Help, Hoe, Hay, Harvest for Victory.”

Other examples further pushed the link between farm work and military service.

In one poster from the federal Department of Labour, a farmer stands tall with a pitchfork resting on his shoulder like a rifle. In front of him are the words “FARMERS: CANADA NEEDS YOUR HELP THIS WINTER.” Another outlines how Canadians can “SERVE BETTER MEALS AND SERVE CANADA’S WAR EFFORT” by using more fruits, vegetables and milk. Even the famous “ATTACK ON ALL FRONTS” poster features an apron-clad woman brandishing a hoe, easy to miss below the soldier and munitions factory worker.

Knowledge gaps

Such campaigns helped address the farm labour shortage, but there were downsides to the influx of workers as well. Not everyone being called to work on farms was familiar with farming.

“There’s this underlying feeling, especially with the farm labour programs, that farming is unskilled, right? Anybody can pick it up and do it. And that’s not true at all,” Barker noted.

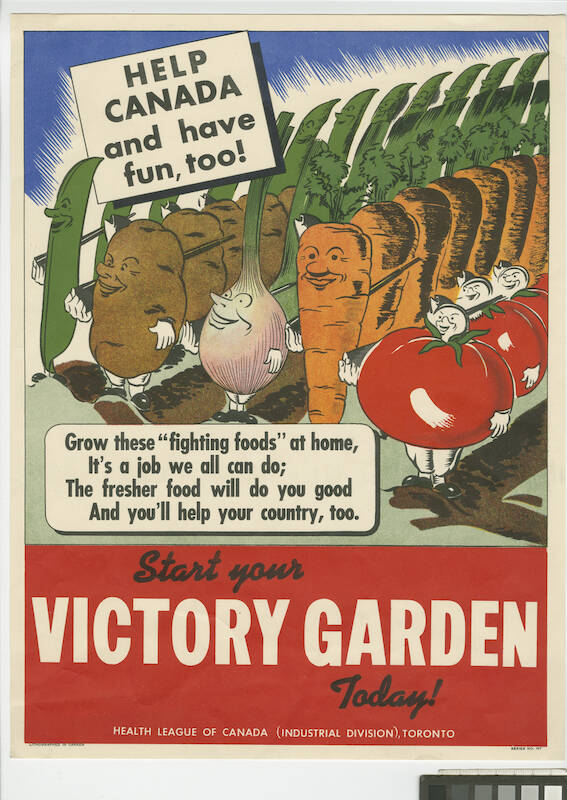

What inexperienced Canadians could do, however, was grow small quantities of food on their own land. One poster encourages Canadians to start their “victory garden” by planting “fighting foods” like tomatoes, onions, carrots and potatoes at home. Accompanying the message were images of vegetables, lined up and marching in unison with rifles on their shoulders — little nutritious soldiers doing their part.

“It shows you some of the themes that are coming up: This is our strength. Agriculture, of course, is one of the ways we’re contributing to the war effort in a very significant way,” Barker said.

Post-war attitudes

War-time agriculture and agriculture policies would end up having impacts beyond the end of the conflict.

Canada’s Official Food Rules, for example, outlined in a poster where a young woman looks up at a table of recommended servings in a grocer, would eventually develop into the Canada Food Guide, which would become a fixture of elementary school health classes from coast to coast for decades.

“It’s an outsized impact that they had on the war effort,” Barker said. “When you consider how small the farming population really is and how important food was, they don’t get their due in how we conceive them and think of the war.”