The debate on balancing housing demand with agricultural land protection continues to build as agricultural associations draft provincial planning statement letters.

It was a hot policy topic at the Christian Farmers Federation of Ontario’s June provincial meeting in Elora, where members shared their concerns before the Aug. 4 comment deadline.

Why it matters: Housing continues to be gobbled up by development, especially for housing, resulting in less available farmland.

Read Also

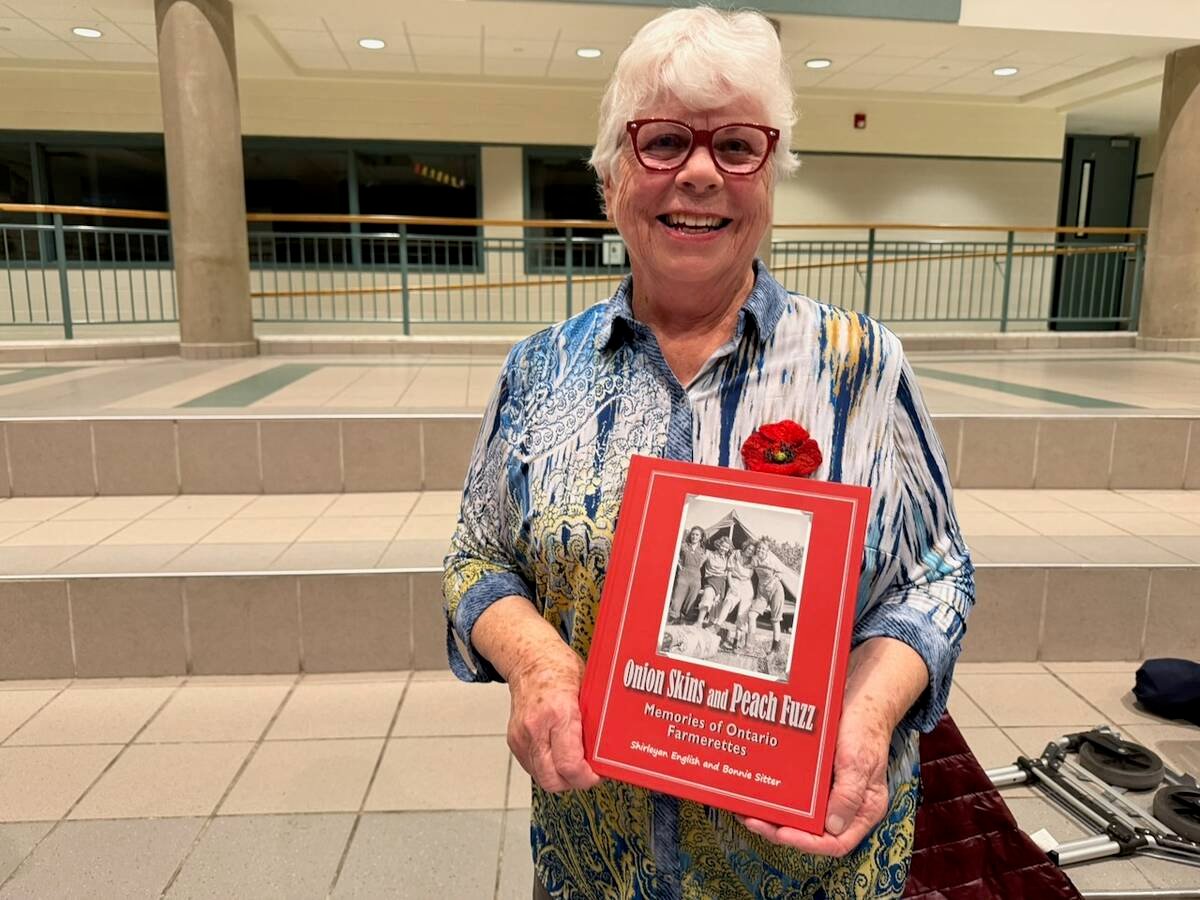

Women who fed a nation

More than 40,000 young women supported the war effort between the 1940s and early 1950s, helping grow and harvest crops amid labour shortages. They were called Farmerettes.

In April 2023, the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH) proposed an integrated province-wide land use planning document incorporating policies from A Place To Grow and the Provincial Policy Statement 2020.

“For the most part, the unique policies that were in the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) (under A Place To Grow) are not being carried forward into the new proposed plan,” said Suzanne Armstrong, CFFO director of policy and research.

“That includes things like the ag system mappings… that are getting lost.”

The province added natural heritage policies to the policy statement draft on June 16 but didn’t address overarching agriculture land protections.

CFFO supports intensified housing in rural areas within settlement area boundaries, expansion of service settlement areas and additional residential units on existing residential rural properties.

However, their stance urges the government to consider the long-term impacts on food production, the environment and safety.

“All of us would like to see much stronger protections, more land designated specialty crop, recognizing different things like microclimates that also impact what can be grown,” said Armstrong. “This is definitely concerning that instead of protecting more, this is drawing back on the protections that would be in place.”

CFFO’s draft letter asks for more precise language around the maximum size of additional residential units relative to the size of the principal dwelling, and prohibiting future severances of such residential units in rural areas.

Additionally, CFFO said new residential units in prime agriculture areas shouldn’t be permitted outside of what’s currently outlined in the 2020 provincial statement and should retain requirements avoiding high-quality farmland for potential settlement area boundary expansion.

The 2020 policy statement from the province permits severance of a residence surplus to a farming operation because of farm consolidation, provided the new lot is limited to a minimum size for appropriate sewage and water service, and new dwellings are prohibited on any remnant parcel of farmland created by the severance.

The proposed planning policy removes protections placing specialty crops and farmland on the low end of boundary expansion options.

“Local planning authorities should be permitted to have stronger protections on farmland, stronger restrictions on lot creation and severances, as well as other policies to support overall agricultural system and vitality of farm businesses as best suits that means a local area,” said Armstrong.

Members spent a great deal of time discussing the potential benefits or limitations of being able to provide family members with additional housing on the farm.

“This issue of the three lots permitted per parcel of prime ag areas has been something that’s really caught people’s attention,” she said. “Rural planners and farm organizations, obviously, we’re very concerned about the potential impact of this… in terms of minimum distance separation impacts on expanding livestock or adding livestock.”

CFFO ran a two-question member survey from May 31 to June 10, with 311 responses answering whether they liked the three-lot severance, a one-lot severance or the current rule. The second question asked members to explain their choice.

Armstrong said the current rule received better than half the votes, with the single and three severance options evenly splitting the remaining votes.

Across the board, members noted that farmland protection, neighbour conflict, MDS/restrictions on farming and food security made up the top five concerns. However, the single and three-lot support cited a desire to provide residence for family, children, or retirement.

“The current rule really favours bigger farms because you can’t have a severance under the current rule until you own essentially two farm properties,” Armstrong explained, adding then the extra house can be severed. “There’s an element of lack of fairness. So, the original farmer who owns that farm and wants to retire doesn’t get to sever off the lot and sell it, but the neighbour can buy it and do exactly that.”

Property rights, the freedom of farmers to do what they want with their land, and the need to raise capital for retirement or if the farm is struggling, or poor-quality land that would be ideal for housing found support in the single and three lot severance policies.

Simon de Boer pointed to the Mennonite practice of building a dotage house on the main home for retired or elderly family members as a potential solution to the lot severance debate.

“The average length of retirement home for the former farmers to stay on the farm was only three years,” he said. “The reality is not a lot of those houses will trade hands, not all will sell, because they’re usually on the farm close to buildings.”

John Markus of Oxford pointed to a study of the Upper Thames Water basin by the local conservation authority, which showed weeping tile beds caused a third of the water pollution. He said three houses without a sewage system was an accident waiting to happen, regarding farm tile getting leached and causing unmitigated damage.

Armstrong told the members to invite municipal and provincial government officials and land use planners and express the concerns of the agriculture community around the planning policy language.

“Here in Middlesex, Oxford and other counties, especially where there’s a lot of farming, we are very concerned about what’s being proposed,” she said. “We are not alone. We have allies, certainly again, in municipal land regional governments who are interested in these concerns as well.”