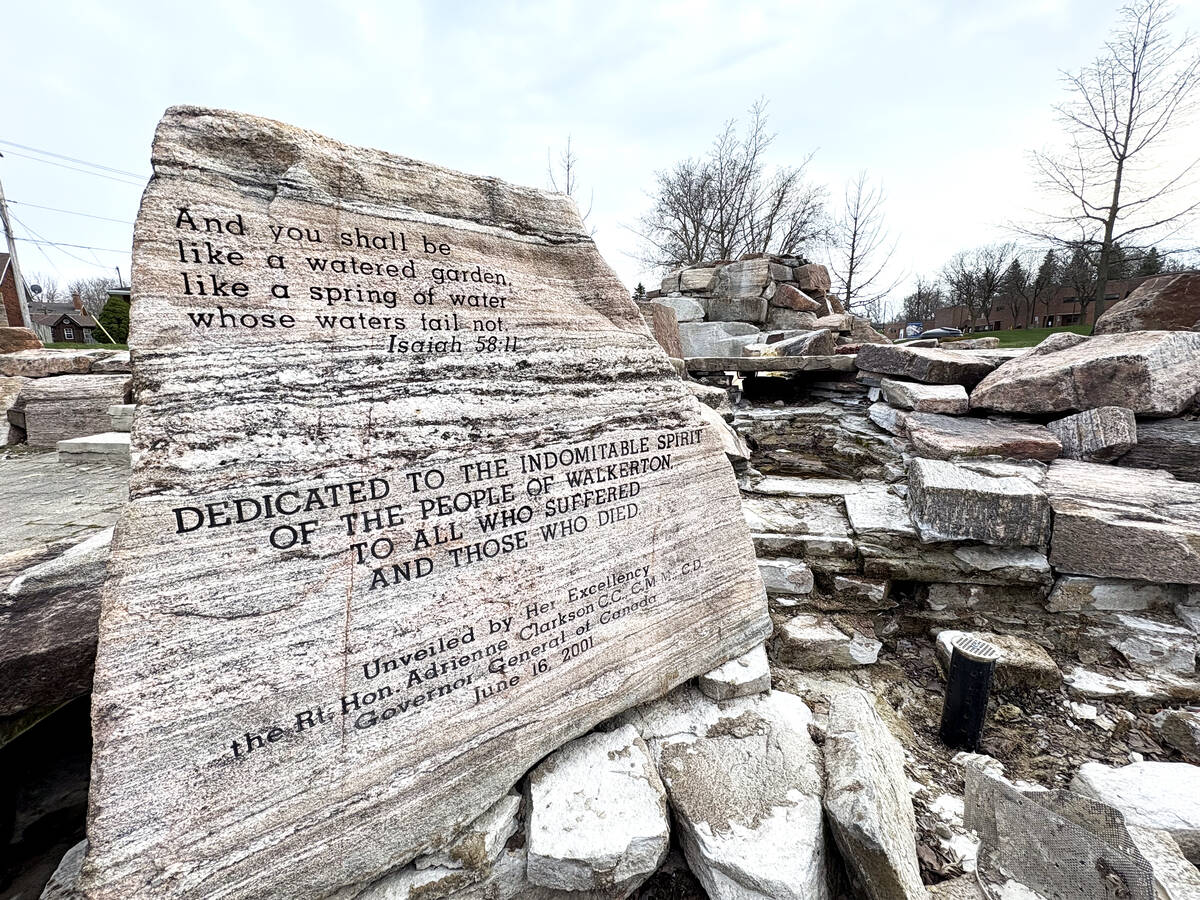

Water is powerful. It’s vital for survival, but when left unchecked it can carve an indelible mark on the landscape.

Or in the case of Walkerton, a community.

In May 2000, as a rookie photojournalist I obsessively followed images from big-city colleagues documenting the devastating effects of contaminated drinking water in Walkerton.

The images reflected a community overwhelmed by tragedy, funerals and uncertainty, while print and broadcast journalists summarized the investigation and its potential sources.

I vividly recall media reports tracing the E. coli source to David Biesenthal’s farm, but I missed his eventual, quiet exoneration, which was merely a footnote in the coverage of the inquiry that followed.

Read Also

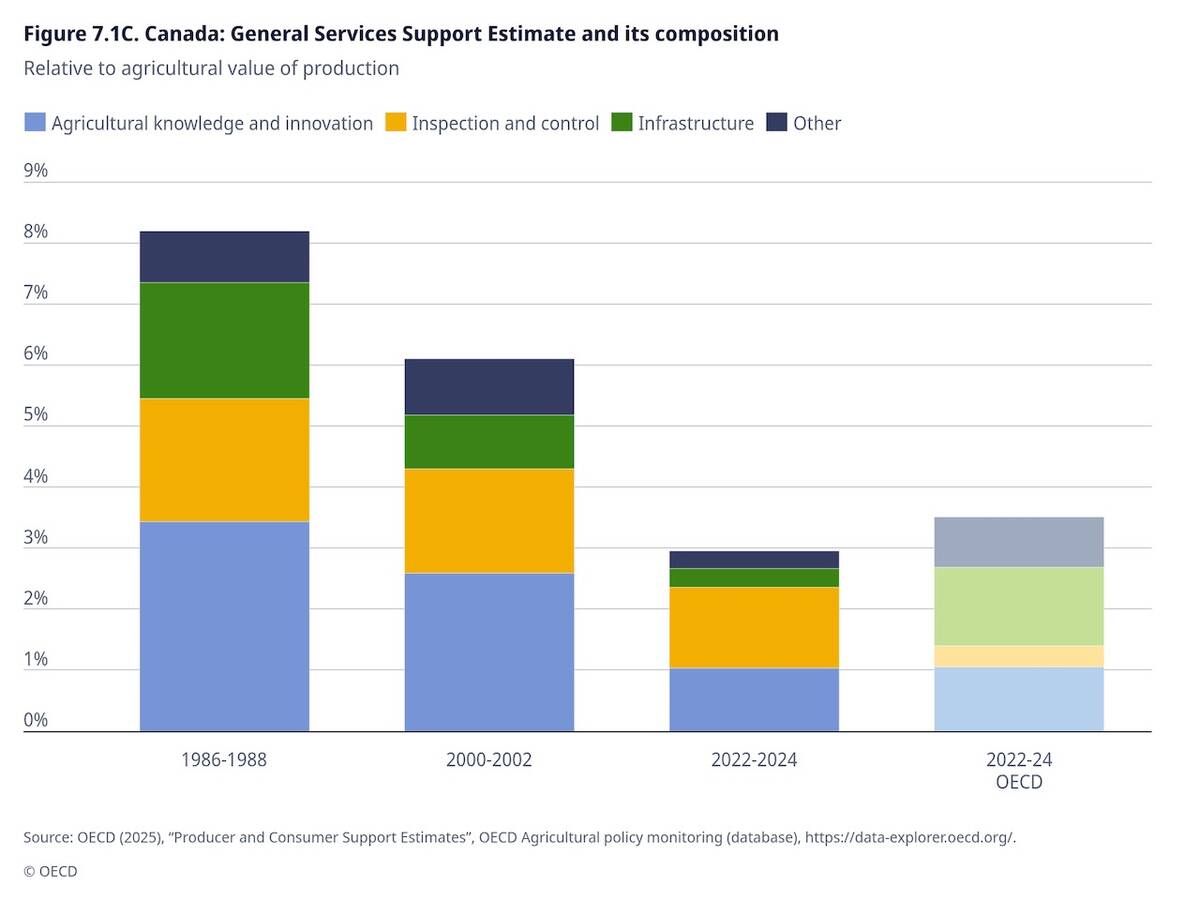

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

As happens with news cycles, my attention waned during the government’s multi-level pass-the-buck accusations. By the time the Walkerton Inquiry Report was released and the Koebels’ trial occurred, my focus had shifted to my community coverage.

In the report, Justice Dennis O’Connor stated on page 105 “The primary, if not the only, source of the contamination was manure that had been spread on a farm near Well 5, although I cannot exclude other possible sources.”

Further down he noted, “at the outset that Dr. David Biesenthal, the farm’s owner, engaged in accepted farm practices and cannot be faulted for the outbreak.”

Many media publications used “should” instead of “cannot,” creating a sliver of doubt.

Only when I began covering the 25th anniversary of Walkerton for Farmtario did my bias of misinformation become apparent, and I realized I’m not alone.

The bias affecting the Biesenthals a quarter of a century later is subtle, often rooted in beliefs stemming from early reports and a lack of clarification or exoneration in the media.

While in Walkerton to speak with the Biesenthals and take photos around town, locals stopped to ask me what I was photographing. This provided an opportunity to strike up conversations and during one of these encounters a dairy farmer during the water crisis revealed how deeply entrenched Biesenthal’s perceived responsibility runs.

She and her husband shared how their children fell ill from drinking water at the babysitter’s house in town and mentioned in passing, with no malicious intent, that the manure spread by Biesenthal was at fault.

Technically, the E. coli source was manure; however, Justice O’Connor ruled that the outbreak could have been prevented if Well 5 had provided continuous chlorine residual and had turbidity monitors to sound the alarm and shut off the pump. Additionally, the report stated that positive E. coli tests from a spring discharge near Well 5 on June 6, 2000, indicated contamination of the large bedrock area underlying the well.

The advice from Mike McMorris, then manager of the Ontario Cattlemen’s Association, to use third-party expert verification to enhance transparency in agricultural practices and provide the public with bite-sized information was crucial. And it extends beyond just crisis mitigation.

It’s a tool that every journalist should use, especially if we want to inform the public about the importance and fragility of agriculture, protect agricultural land, and build confidence and trust in Canada’s agriculture sector.

But there’s another one we must hone.

In conversations with David and Carolyn Biesenthal it is evident from the occasional, shockingly sharp comments and accusations still aimed at them that some residents remain steadfast in attributing guilt.

It’s a powerful reminder of our responsibility to provide accurate information in our coverage and to dedicate equal passion and commitment to clarifying misinformation.

How different might Biesenthal’s experience over the last 25 years have been if journalists, quick to aim their hair-trigger poisoned pens at him, had worked just as diligently to exonerate him with facts?