When it comes to research and industry knowledge transfer, there’s a “what came first? The chicken or the egg?” dilemma.

Why it matters: Farmers benefit when research is conducted to help solve problems or improve efficiencies on-farm.

Does industry need drive research, or does research identify gaps and then offer industry solutions?

When done well, it turns out, it’s a bit of each said presenters at the Livestock Research and Innovation Corporation’s annual Getting Research into Practice (GRIP)’s “Benchtop to Barnyard” roundtable in Elora, Sept. 30.

Read Also

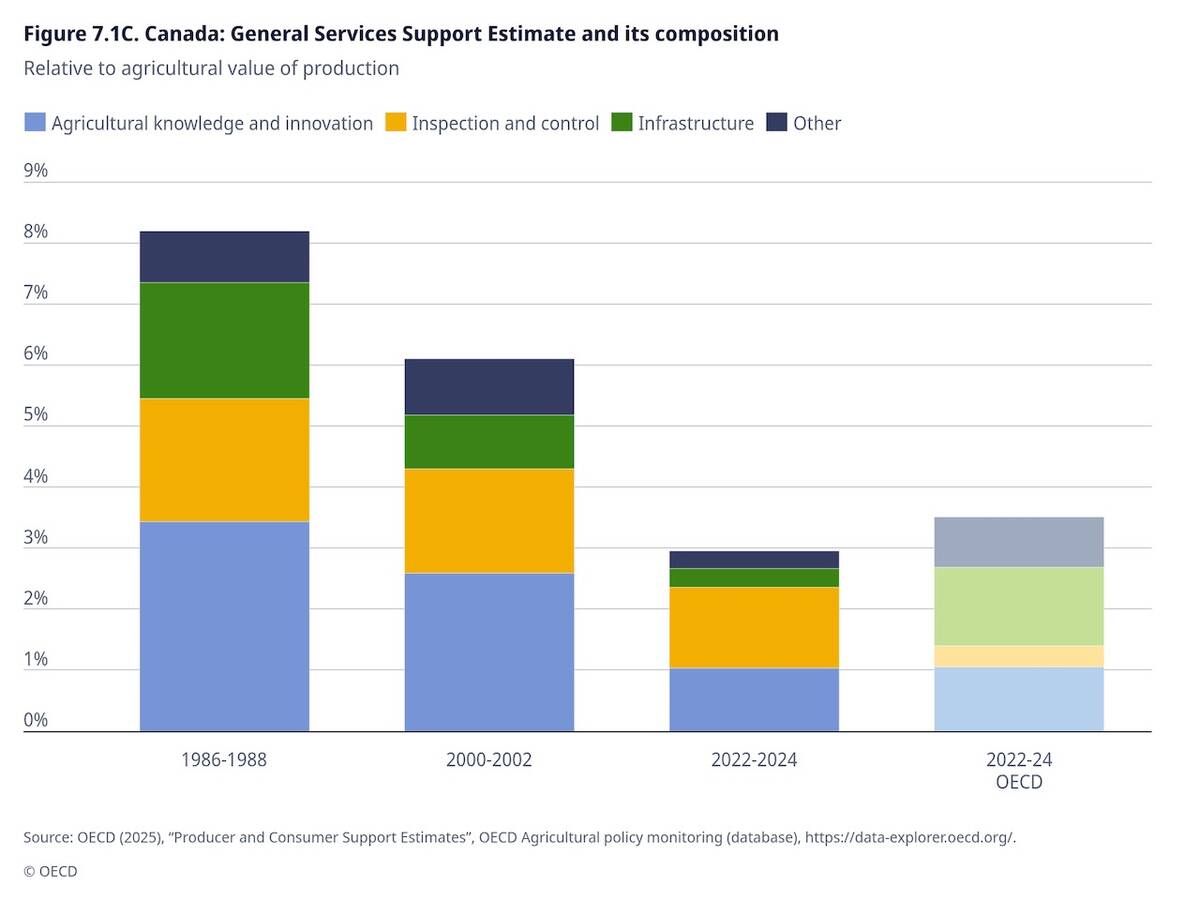

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

Dr. Tina Widowski, from the University of Guelph department of Animal Biosciences and Egg Farmers of Canada poultry welfare research chair, pointed to livestock codes of practice or the development of a non-penetrating captive bolt for humane euthanasia in poultry as prime examples of successful industry partnerships and practical research.

“When it comes to animal welfare, it can’t be opinion-based. It has to be fact-based. It has to be objective,” Widowski explained.

The codes of practice provide guidance on the care and handling of livestock. The codes’ development includes a variety of stakeholders, including farmers, veterinarians, government, animal advocacy groups and occasionally retailers.

These partnerships also provide a conduit for researchers to have their work published in relevant publications or guides, helping advance the industry.

For example, Widowski has performed research the examine the impact on productivity and welfare measures when introducing laying hens to enriched colonies with a higher space allowance, curtains, and a scratch mat. This research filled a knowledge gap that existed to inform the recently updated Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens.

Widowski advised all levels of researchers and students to spend time in the barn, take that farmer phone call, build relationships, and develop a comprehensive understanding of farm operations so that research can be translated into achievable solutions.

Dr. Alexandra Harlander, veterinarian and animal welfare scientist with the U of G, partnered with farmers as well as provincial and national poultry boards to collect data for a benchmarking study to develop a feather cover scoring system for Canadian laying hens in free-run and enriched housing systems.

Feather pecking is an abnormal behaviour leading to naked birds and potential cannibalism, resulting in increased feed, heating, and mortality costs, explained Widowski.

The system has been adopted and adapted for use by the Egg Farmers of Canada and translated into several languages.

“This was a beautiful collaboration with industry,” Widowski said, adding on-farm applicable research helps secure funding, especially through commodity groups. “And you can find research that has direct application to informing guidelines and practices because we (animal welfare sector) have a natural conduit for doing that.”

Problem-solving approach

Dr. Jennifer Ellis, an associate professor of Animal Systems Modelling at the U of G and a former Trouw Nutrition poultry research scientist, said that starting research from a problem-oriented perspective, rather than trying to force a solution, is more effective.

Ellis, who develops and refines mechanistic models and machine learning algorithms to understand and improve the relationship between animal physiology, digestion, and farm production, was inspired to create a pellet quality app after a failed poultry nutrition trial.

She believed that using machine learning to leverage untapped feed mill data, an algorithm could predict pellet quality and improve manufacturing methods in commercial feed mills.

Approaching her existing contacts at Trouw with the proposal led to an introduction to Molesworth Farm Supply’s manager of nutrition and production research, Dr. Meeka Capozzalo, as well as connections with Masterfeeds and Walinga.

“I don’t think this project would have been adopted or embraced by the industry as quickly if it weren’t based on relationships and the trust that existed between us,” said Ellis. “In addition, we’ve somehow succeeded in getting competitor companies to work together, because they see the value in this bigger-picture approach to solving this problem.”

Molesworth hadn’t produced pellets but wanted to address potential issues and wondered if increasing their throughput by 10 per cent could also be explored.

“I was extremely happy and relieved that they were willing to add to the research question in a significant way,” said Capozzalo, adding that, from an industry perspective, space to evolve research is critical. “Because, sometimes you think you’re solving a problem, but really your actual problem is something else.”

There were deep conversations about intellectual property and how much information Molesworth was willing to share with the university, industry partners, and who the end users or beneficiaries would be — whether that was decision-makers, policy and regulatory bodies, practitioners, or others — and how they would champion the project.

“It’s really important to identify those early on, address the concerns,” she said, adding it’s critical to engage the end-user and secure buy-in early.

“Also make sure that you’re really selling the value of what this project can do and how it will benefit them.”

The definition of a “problem” is shaped by each stakeholder’s perspectives and may not align.

Solutions to farm-level problems could be driven by the sustainability, affordability, adoptability, or adaptability of the solution, resulting in improved operations. Meanwhile, industry, policymakers, regulators, or other stakeholders are often interested in the bigger picture or in-depth data analysis, said Capozzalo.

When designing research, scientists need to recognize who is executing it, understand their personalities or care factor, and, if they’re producers, listen when they share their issues.

“I think a lot of producers don’t really realize they’re already researchers, (and) are hungry for knowledge and hungry to try new things,” Capozzalo explained.

“A lot of people still think research needs to be hard for it to be good, but I don’t think that’s necessarily true.”