Agronomists, nutritionist and farmers can work closer together as a team to create better forage-based results for livestock farms.

A passionate field-to-food panel with all three focused on the importance of proper harvesting techniques, high-quality forage assessments and waste reduction during the Canadian Forage and Grassland Association’s 15th annual conference in Guelph, Ont., on Dec. 5, 2024.

Why it matters: Increasing forage feed efficacy and harvesting efficiency through better management and quality assessment improves nutrition and minimizes waste.

Read Also

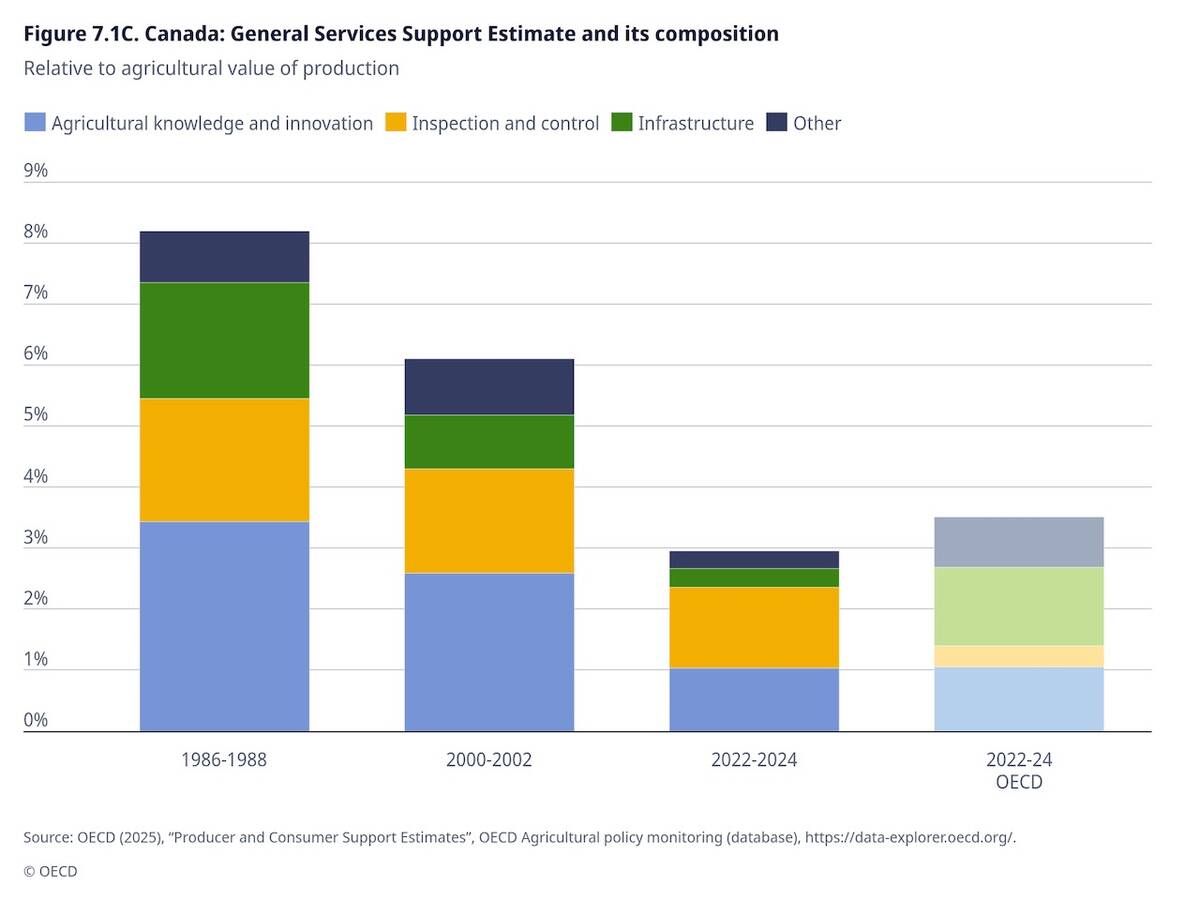

OECD lauds Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticizes supply management

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lauded Canada’s low farm subsidies, criticized supply management in its global survey of farm support programs.

Panellists, Tom Wright, a dairy cattle specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA), Courtney Vriens of Vriens Nutrition Consulting and independent certified crop advisor Patrick Lynch agreed that more collaboration between agronomists, nutritionists, and farmers is needed to assess what worked to move the goalposts.

“That’s got to come from the farmer. He’s got to say, ‘I need the two of you in the place at the same time,’” said Lynch. “The agronomist will probably ask the nutritionist questions the farmer never thought to ask.”

There’s more value to be found in forages

Wright said fibre digestibility is a key metric for high-quality forages.

“That drives so much in terms of energy,” said Wright. “It leaves room for a nutritionist to put the other packages in that need to go in.”

Vriens said that protein, starch content and clean forage indicators also contribute to assessing forage quality.

“Forages that don’t have soil contamination, low ash content and are fermented properly” are important, said Vriens, who also produces sheep. “That, and fibres are the two most important things.”

From an agronomist’s perspective, Lynch said quality forage production begins in the field, whether it’s magnesium or sulphur inputs, harvesting techniques or waste reduction.

Lynch, a former OMAFA crop specialist, ramped up the crowd with an impassioned assessment of current harvesting practices, which result in 10 to 20 per cent in-field forage feed waste annually. For example, he said some producers use windrows despite indisputable research that laying forages flat is superior.

There was some fiery banter when Lynch suggested that nutritionists would rather sell magnesium to farmers than tell them to put it in the field.

“I won’t tell farmers about nutrition, and, in return, nutritionists are not going to tell farmers how to grow crops,” Lynch fired good-naturedly. “I get a little bit irate when I have a nutritionist telling the farmer what population to plant a corn hybrid at. Come on, give me a break. That’s our job. You stick to nutrition.”

Lynch said magnesium and sulphur applications are no-brainers to increasing forage quality. Still, nothing gets his dander up more than not spraying to reduce DON and control fusarium in corn silage, which is problematic.

“We have to be doing a better job at maintaining the quality that we agronomists have grown,” Lynch said, adding bunk audits can pinpoint problem areas too.

Vrien said storing forage that’s too wet, higher than 68 per cent moisture, and fermentation issues can result in improper pH levels, dry matter and nutrient loss, and increased potential for listeria growth at the feeder once exposed to oxygen.

“The fermentation profile (in the feed analysis) is basically like looking at everyone’s dirty laundry,” agreed Wright. “We know where the mistakes have been made.”

He said many large dairies aren’t achieving more than 13 to 14 pounds per cubic foot of dry matter after packing, which is related to tractor time, weight, particle length, and moisture content.

“I would say these are correctable,” said Wright.

Vriens and Lynch agreed producers should harvest forage when conditions are favourable despite the weather risks. Vriens said rations can be balanced against lower quality but not poorly fermented feed and livestock health risks.

“The bottom line is, if you can’t make good forage with today’s weather, then you obviously can’t cut it,” added Lynch. “But it’s really an individual farmer-by-farmer, grower-by-grower call (based on) how much feed you already have and what’s the quality of it?”

One in five or six dairy samples from the Ontario labs, Lactanet, or Dairy Forage One in New York, displays identifiable and avoidable mistakes, such as heating, fermentation profile, ammonia content, unachieved lactic acid or pH balance, or a lack of inoculant use.

Wright said inoculant use data suggests it has a good payback most years because of variable conditions.

Fielding a question regarding triticale acres overtaking alfalfa and usurping the forage in dairy and sheep rations in parts of Ontario, the nutritionists and agronomists again presented opposing responses.

Vriens and Wright noted that triticale’s 17 to 17.5 per cent protein and high fibre digestibility could achieve a producer’s target if harvested at the proper maturity.

While Vriens doesn’t anticipate alfalfa elimination from the dairy sheep ration, she could see triticale as the go-to for meat sheep rations.

“Alfalfa is such a good feed for dairy cattle that I don’t see it disappearing 100 per cent, but I see the advantages of triticale that people have been using the last few years,” said Wright. “There’s a lot of enthusiasm for it, and some of the digestibility factors are unparalleled.”

Lynch suspects triticale use increases are influenced more by nutritionist’s desire for an easily balanced ration, than the economic efficiency of the crop.

“Why are they growing with triticale instead of an alfalfa-grass? Well, it’s a lot easier to balance the ration with triticale. It’s the same for the whole field and the whole farm,” he said, adding that is possible with alfalfa, too. “Let’s research (alfalfa’s) nitrogen value, and then we’ll start getting more acres.”

Wright cautioned that the results may vary yearly because Mother Nature influences quality, quantity, and inventories, but having a common language and understanding helps achieve the goals.