Atmospheric rivers are storms akin to rivers in the sky that dump massive amounts of rain and can cause flooding, trigger mudslides and result in loss of life and enormous property damage.

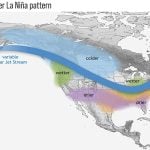

This weather system occurs all over the world. It starts when a large amount of water vapor from tropical oceans is carried by a jet stream toward land. As the air rises, it cools and condenses, resulting in rain or snow. They most commonly form in mid-latitude oceans, roughly 30 and 60 degrees north and south, according to NASA. They appear as a trail of wispy clouds that can stretch for hundreds of miles.

Read Also

Prairie forecast: Warm start, then cooler

Prairie forecast calls for warm temperatures to give way to cooler, wetter weather week of Oct. 22-29.

Atmospheric rivers can carry up to 15 times the volume of the Mississippi River, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Most atmospheric rivers are weak and do not cause damage. They can provide much-needed rain or snow.

Sometimes they do both. In drought-stricken California, such storms have triggered mudslides, toppled utility poles and blocked roadways, but also helped replenish depleted reservoirs and reduced the risk of wildfires by saturating the state’s parched vegetation.

In 2019, an atmospheric river nicknamed the “Pineapple Express” hit California. The water vapor from near Hawaii brought rain and triggered mudslides that forced motorists to swim for their lives and sent homes sliding downhill.

In 2021, an atmospheric river dumped a month’s worth of rain on British Columbia in two days, prompting deadly floods and landslides, devastating communities and severing access to Canada’s largest port.

According to scientists, atmospheric rivers of the kind that drenched California and flooded British Columbia in recent years will become larger—and possibly more destructive—because of climate change. There are projected to be 10 per cent fewer atmospheric rivers in the future, but they are expected to be 25 per cent wider and longer and carry more water, according to a 2018 research paper.

This could make managing water supply much harder as moderate atmospheric rivers, which can be beneficial for water supplies, will be less frequent, and strong ones could become more calamitous.