Water quality can affect spray applications in how well the product mixes and how the sprayer performs. It can reduce product efficacy and result in negative environmental impacts.

Jim Reiss from Precision Laboratories in Kenosha, Wisconsin, explained several water quality issues during the second day of the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association’s annual meeting last month in Elora.

Reiss, senior vice-president of product development, provided his expertise on the largest effects on sprayer performance.

Read Also

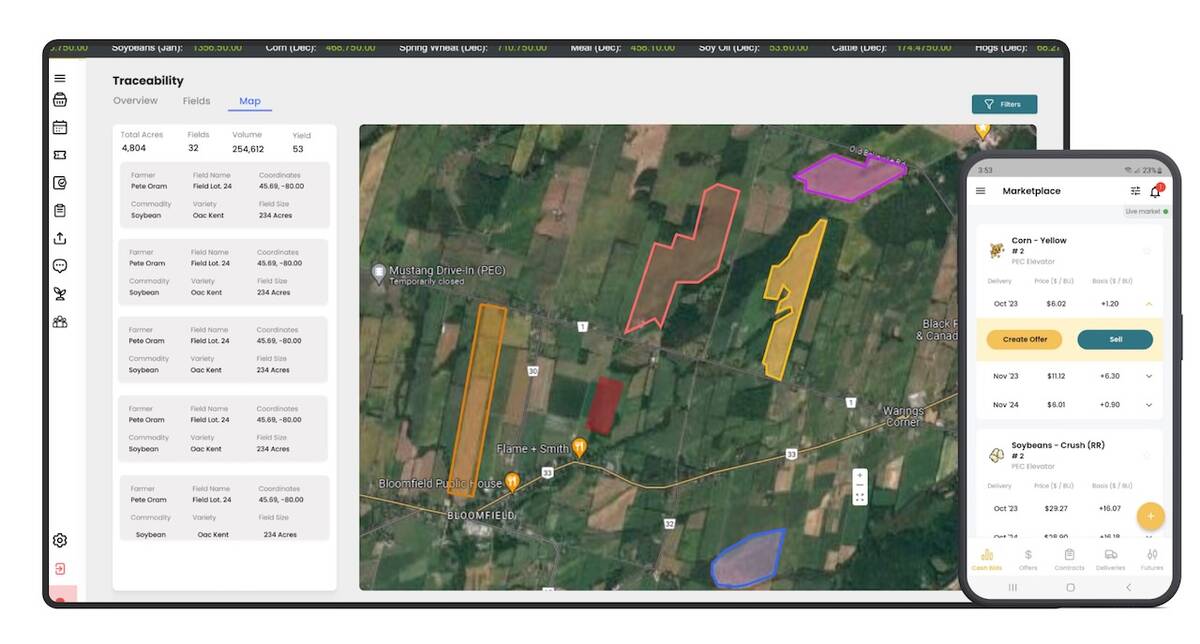

Ontario company Grain Discovery acquired by DTN

Grain Discovery, an Ontario comapny that creates software for the grain value chain, has been acquired by DTN.

Why it matters: Water quality varies from one farm to the next due to hardness, temperature, pH and other chemically related properties.

Reiss first outlined the effects of turbidity, which is simply water that contains suspended solids such as clay, silt and organic matter. Although it has no impact on mixing or spraying, turbidity can reduce efficacy.

“Assuming you’re not sucking up leaves and sticks or algae, it’s not really going to affect mixing,” said Reiss.

“But it can have a huge impact on things like glyphosate and diquat (Reglone) and paraquat (Gramoxone). This is the easy one to avoid but you might have to use well water.”

Conductivity or total dissolved solids (TDS) do not affect mixing or spraying but could affect efficacy. It’s the sum of cations, particularly those that can antagonize weak-acid herbicides, like calcium, magnesium, manganese, sodium and iron, and also covers all anions – bicarbonates, chlorides, nitrates and sulphates. The problem can be identified by measuring electroconductivity.

“This is really your quick, low-cost indicator to say ‘I need to learn more about what’s going on here’,” said Reiss.

“This is a ‘big-picture’ thing, so if your TDS score is 325 parts per million or less, you probably don’t have much of a problem with your water. If you’re showing readings of 325 or more, I’d want to know more about my water.”

Hardness was Reiss’s key indicator for getting a water test. Calcium and magnesium can tie up glyphosate and glufosinate, while readings of 600 ppm can render 2,4-D-amine useless and also affect dicamba. The presence of sodium and iron is also a concern.

The answer, said Reiss, is ammonium sulphate (AMS) in the tank.

“The first thing that happens is the ammonium ions and the sulphate ions separate and will start to make friends with these antagonistic mineral ions. The ammonium ion tends to associate with the glyphosate molecule and makes it much easier for ion trapping and managing hard water.”

How much AMS is needed?

Reiss provided a formula involving soil test levels of sodium, calcium, magnesium and iron, along with potassium, to calculate how many pounds of AMS were required:

0.002 x K ppm + 0.005 x Na ppm + 0.009 x Ca ppm + 0.014 x Mg ppm + 0.042 x Fe = lbs of AMS/gallon.

He is often asked whether AMS should go in a spray solution first. The answer is no.

By accident, a group in North Dakota learned that adding AMS last had no negative impact on mixing at any time during the process.

Bicarbonates, ammonium thiosulphate and temperature are other water ingredients that can affect spray efficacy. Bicarbonate, or alkalinity, depends on the presence of calcium and sodium to inhibit herbicide performance.

Readings higher than 500 ppm inhibit 2,4-D-amine, MCPA-amine and can increase pH. Using AMS and UAN can be effective at countering bicarb and certain acid-based water conditioning agents can help neutralize the effects of bicarbonates.

Ammonium thiosulphate (ATS) has to be used with care, said Reiss, alluding to research from Purdue University in 2019. In its conclusion on weeds such as barnyard grass, velvetleaf or lamb’s quarters, or with cover crops like wheat or annual ryegrass, potential control “could be lower or result in incomplete kill if ATS is used with a burndown herbicide program that relies on glyphosate or glyphosate plus 2,4-D.”

Temperature

Water temperature can reduce the initial emulsification in pesticides, although Reiss conceded it’s a low priority. However, colder water can present challenges.

“It just takes more time for things to go into solution, and you should be stretching out the time between adding the first product in the tank mix versus the second product versus the third product,” he said.

“Everything has a chance to disperse and you’ll see compatibility agents help, but it’s going to take more time.”