Seven years ago, Lawrence Hogan and Steve Howard decided to change their tillage management.

They had worked for decades with a variety of tillage systems, from ridge to minimum, strip till to no till, and then decided to replace the tillage implement with plants.

In 2015, they tried no-tilling corn into a mix of summer-planted, multi-species cover crops and some frost-seeded red clover. Two years later, the brothers began using biostrip till on their farms near Lucknow, which includes the use of winter-planted cover crops.

Read Also

The forced Japanese-Canadian farmers of the Second World War

Manitoba’s sugar beet farms drew on displaced Japanese-Canadians from B.C. during the Second World War

Why it matters: Biostrip till can offer improved soil health, protect corn plants against drought and reduce the need for inputs.

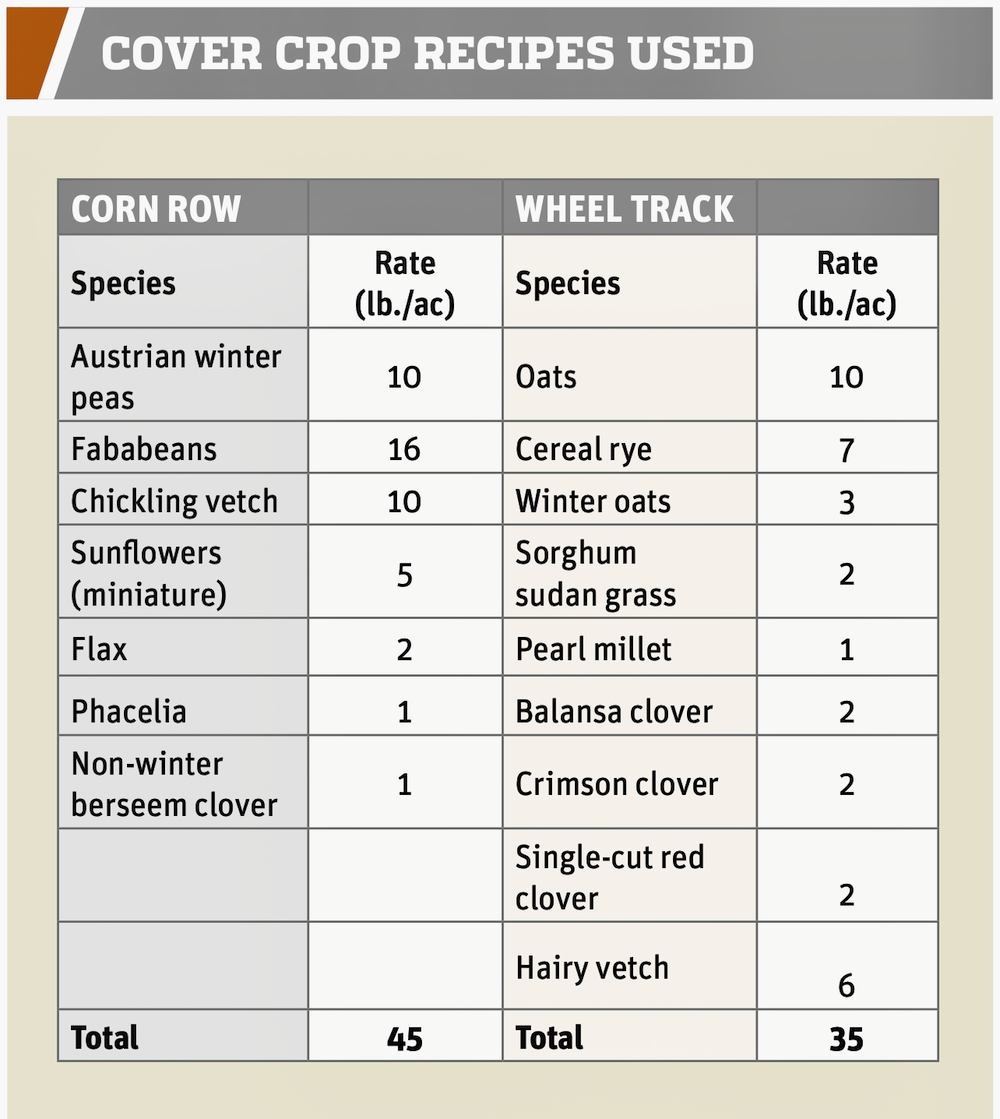

Biostrip till systems involve two separate cover crop recipes. The wheel row recipe contains overwintering species that produce roots and nutrients for soil biota and the new corn crop, while plants in the corn row will terminate with winter frosts.

They use a special implement from Quebec, which has two gangs of row cleaners per 30 inches of row, mounted on a three-point toolbar.

The two gangs are arranged with the second gang behind and wider than the first set. This clears a 10-inch path of the dead cover crop residue from the corn row. The row cleaner is pulled through the field ahead of planting and results in a seed bed that’s been “tilled” by plants with no interference from the residue.

Row cleaners are also mounted on the corn planter. The living plants in the wheel row will ensure the area where corn is planted sees almost no traffic. The living plants and non-tilled soil improve weight-carrying capacity and reduce soil compaction.

The wheel row cover crops are terminated with a conventional burndown and residual herbicides before, but usually after, corn planting, depending on the year and level of growth.

The two men manage a strict rotation of corn, soybeans and wheat on their farms, and Howard has about 100 sheep on land not suited for cropping, which is in pasture and hay.

Although Hogan concedes the use of minimum and no-till systems eased the transition to biostrip till, he and Howard have tinkered with the cover crop recipes (see Table) and have set their standard blends within the past three years.

“If you’re concerned about a multi-species blend or too much biomass, there are a couple of ways you can deal with that to start with,” says Hogan. “One would be to plant later or plant thinner with species that have less biomass.”

“For someone first starting into it, they don’t have to have as complex a blend that we have,” adds Howard, noting a seed drill with a grass-seed box will do the job.

“They could modify it without going to a lot of expense. You just have to make sure you have the right species. With a grass-seed box, you wouldn’t be able to have any large seeds.”

Small setback

This past spring, Hogan and Howard noticed effects from the cereal rye and hairy vetch planting, particularly the latter, which overwintered better than ever. It shaded the soil and slowed the drying process. In retrospect, the two believe they should have gone in earlier with the row cleaner to push the live vetch back and speed drying.

As for the positive effects of biostrip till, Hogan calls their yields “comparable”. Going back seven years – the length of time he’s been no-tilling corn – yields have increased, although he credits plant genetics and favourable weather conditions for some of that.

“Visually, I’ve noticed that at corn planting, soil conditions have a really nice texture with that aggregated soil,” says Hogan. “The soil’s protected, especially if you leave the cover crop alive through the winter.

“You see it more so in the wheel track strips than you do where you’re actually planting in the corn row strips. It lasts longer because there are more roots that are still alive.”

They removed the coulters several years ago before owning their row cleaning implement, believing it was doing more harm than good. If it is too damp, coulters smear the soil and if the soil is too dry, the coulters tended to bring moist soil to the surface where it was lost to the seeds.

Back to basics

It’s an appealing concept to Ian McDonald, crop innovation specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. He acknowledges the interest in biostrip till practices by growers and by researchers Laura Van Eerd and Josh Nasielski from the University of Guelph.

“This is getting back to that chaotic aspect of nature, which is why we run into problems when we try to tame nature instead of working with it,” says McDonald.

“I like the ground cover and the biology supporting plants throughout most of the season and supporting that microflora population.”

McDonald acknowledges lack of buy-in from a large part of the farming community, organizations, academia and government. Yet over time, and in spite of the need for continuous adjustments in the system, all indications point to biostrip till improving soil health and crop profitability.

“You’re going to get a higher level of organic matter in that soil, which is going to hold more nutrients,” says McDonald. “It’s going to hold more plant-available water so you’re going to be less drought-sensitive.”

The key is getting growers like Hogan and Howard to share their message. Like McDonald, Hogan likes what he sees from his soils.

“I don’t think there’s any better look than a live cover crop going into the winter,” he says. “It makes scientific sense that if you’re not leaving your soil susceptible to the elements, that it’s going to improve.”